Well, here we are. The Giants won another World Series, while the A’s flopped in the playoffs yet again. I’m not one of those A’s fans who hate the Giants, but it’s starting to annoy the crap out of even me to see the Giants always succeed in the playoffs, while seeing the A’s always fail.

The A’s have had 14 chances in the last 14 years to win a game to advance to the next round of the playoffs. They have lost 13 of those 14 games. If the playoffs are truly a crapshoot, the odds of this happening are 1-in-1,170. (So it’s not technically always — they could have gone on to lose the 2006 ALDS against the Twins, too, which would have made them 0-for-16, with an unlikelihood odds of 1-in-65,536. So if you want to look on the bright side, things could be 56 times worse than they are.) And in a crapshoot, the odds of the Giants winning 10 playoff series in a row, as they have now done, is 1-in-1024.

So if you’re an A’s fan who hates the Giants, and who believes that the playoffs are a just crapshoot, you’ve been struck with a series of unfortunate events that had literally less than a 1-in-a-million chance of happening.

Sabermetrics has come up with no good explanation for it except to say, well, these things happen about once every thousand times, or once every million times, sorry A’s fans, it just happened to be your turn to hit that unfortunate lottery, and it’s just bad luck. Oh, and you have a crappy stadium that’s falling apart and a team ownership and a local government who all seem too incompetent to do anything about it unlike those guys across the bay, sorry about that, too, gosh you guys are unlucky, tsk tsk tsk.

Which is just a deeply, deeply unsatisfying answer. If you have an ounce of humanity, you will reject that explanation, and ask the obvious question.

And to answer that question, the sabermetrician dives into the numbers, and pulls some out numbers with some number-pulling-out tools, and finds nothing to report. Nope, no evidence here of anything, so it must just be bad luck.

To which I ask: what if the reason the number-pulling-out tools can’t find any cause for the problem is because those number-pulling-out tools themselves are the problem?

I have no evidence of that. But it’s something I believe might be true, even though I can’t prove it.

* * *

I have a number of these beliefs–or hypotheses, if you will–about baseball, but I’ve mostly kept them to myself because of this lack of evidence. What the hell do I know, anyway? Who am I to pontificate? And why bother spouting these theories when I can’t defend them with evidence? So I just keep my mouth shut.

But I got a little bit of self-confidence in my belief system when Robert Arthur of Baseball Prospectus took one of my hypotheses (that injured A’s in the second half of 2014 had begun cheating on fastballs, making themselves vulnerable to offspeed pitches) and found evidence to support it ($):

The overall pattern of changes is beautifully consistent with Ken’s theory…

It’s very satisfying to find that the data supports one’s theory!

But I didn’t just come to this particular hypothesis that Mr. Arthur investigated out of thin air. This hypothesis arose out of a deeper foundation of hypotheses that color the way I look at baseball. I want to put all those hypotheses out on the table now, lack of evidence be damned. And maybe someone (maybe me someday, if I ever find the time and energy and resources and willpower to do so, which hasn’t happened yet) will take those hypotheses and invent the technology needed to find the evidence to support it.

So let’s put it out there.

* * *

Belief Without Evidence #1. A technological Sapir-Whorf hypothesis

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, a/k/a the Linguistic relativity principle holds that the language that a person speaks influences the way a person conceptualizes their world. The obvious example of this is that people have trouble distinguishing between colors if their language does not have a word for that color.

To a certain extent, I believe this hypothesis. Being fluent in both Swedish and English, I know there are certain concepts, such as the difference between belief in an opinion and belief in a fact, where the Swedish language makes clear distinctions (tycka and tro) and English does not. English speakers spend ridiculous amounts of time arguing about these things, and Swedes simply don’t need to. It’s not that English speakers can’t conceptualize the difference between opinion and fact, but doing so is way more difficult in English, because the word “belief” in English is quite fuzzy, whereas in Swedish, the language makes it simply impossible to confuse the two.

I touched upon this in my essay in the 2014 Baseball Prospectus annual, that I believe a similar concept applies to the technology we use. The reason statistical analysis began to influence the way we conceptualize baseball in the 1990s is not because human beings suddenly became smarter in the 1990s. There were statistically informed people who suggested such analysis almost a century earlier. It happened in the 1990s because the price of the technology needed to perform such analysis had finally became reasonable.

The predominant technology we use to perform such analysis is SQL, which is the primary language used to query relational databases. SQL and relational databases are technologies which are built upon set theory. A set is basically an unordered collection of objects.

And this is where I believe that a technological Sapir-Whorf hypothesis applies to baseball. Practically all of our analysis of baseball statistics treats its data an unordered collection of baseball events: pitches, plate appearances, games, series. Standard baseball analysis (the public kind anyway, who knows what is being done inside these organizations) treats its data that way because that’s the way SQL treats its data. The available technology guides our conceptualization of the world. And that leads us to my second hypothesis:

Belief Without Evidence #2. Baseball events are NOT unordered

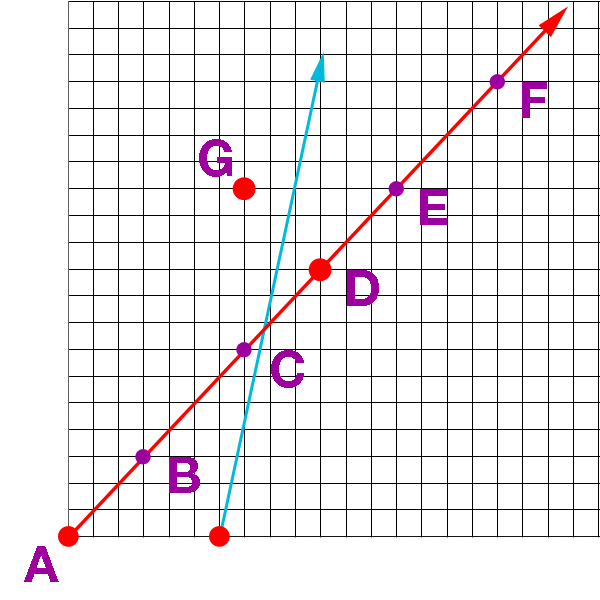

For any batter to hit a ball, the batter needs to predict where the ball is going to be before it reaches the bat. There are two different mechanisms for this prediction.

First, there is a conscious prediction. The batter may decide, consciously, based on some sort of rational analysis, that he is looking for a fastball down and in, and wants to swing at only a pitch in that location that he can pull.

But once the pitcher releases the ball, this kind of conscious prediction mechanism is far, far too slow to be of any use. At this point, everything is turned over to a much faster, subconscious, automatic system to predict the actual flight of the ball, and to send the muscles in motion to meet the ball.

My thoughts here are heavily influenced by Jeff Hawkins‘ book On Intelligence, which lays out a framework for how this automatic system in the brain works as a memory-based prediction machine.

Order matters in baseball, because this automatic prediction mechanism has a strong recency bias. (A conscious prediction might not have a recency bias if truly rational, but how often does a batter perform a purely rational analysis at the plate?) The speed, location and movement of the most recent pitch will affect the brain’s automatic prediction of the speed, location and movement of the next pitch. The more recent a pitch, the more it affects the automatic system’s prediction for the next pitch.

Pitch sequencing, therefore, is at the heart of the very sport of baseball, yet it is woefully understudied in current public analysis, because our tools, based on a foundation of unordered sets, are woefully bad at processing and studying sequenced events.

There is a whole industry now dedicated to the statistical analysis of baseball using these set-based SQL tools. But SQL does not have a recency bias clause in its syntax that you can apply to a query. Because these tools don’t handle the ordered data well, they basically ignore The. Very. Core. of the sport: the sequencing battle between pitcher and batter.

Let me say that again: statistical analysis (that we in the public are aware of) takes the most important element of the sport, and ignores it.

It’s like having Newtonian physics without relativity and quantum mechanics. There’s a lot you can do with Newtonian physics, but at the extremes, it begins to break down, because it is ignoring some deeper, more fundamental truths.

If you’re a team that relies on constructing its roster using such statistical analysis, what mistakes are you making by ignoring the most important part of the game?

Belief Without Evidence #3. All high-level sabermetric truths derive from lower-level truths about human biomechanics and psychology

And not vice versa. Things like platoon splits and home field advantage are not Constants of the Universe like the speed of light or the Planck-Einstein relation. The arise from more fundamental truths about human anatomy and psychology.

For instance, once I got in an argument in which I did not believe that Sean Doolittle pitched better to certain catchers than others. The stats did not agree with me, albeit perhaps with a small sample size. But my objection wasn’t to the numbers, adequate sample size or not, it was to the lack of any sort of underlying physical/psychological mechanism where this these numbers could derive from. Sean Doolittle throws 90% fastballs. What the hell difference physically/psychologically does it make what catcher is back there catching it? It’s the same pitch, no matter who is catching it.

I do not consider a sabermetric truth to really be a truth unless there is a biomechanical/psychological foundation upon which that truth can rest, and from which that truth is capable of being derived.

Belief Without Evidence #4. Pitches are paths between states in a Prediction State Automaton

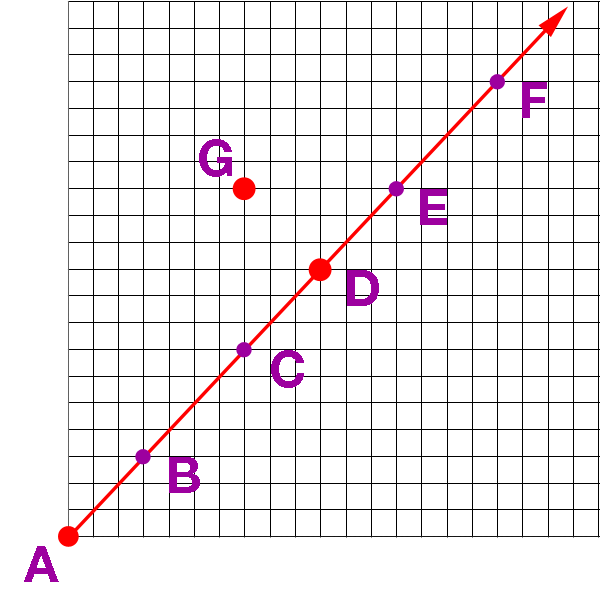

First, a little explanation of automata:

Automata theory is used in computer science to study states. For example, you can look at baseball as an base/out automaton, where before each plate appearance, the base/out combination is in one “state”, and in another “state” after the plate appearance. There are rules that tell you what possible states you can be in before and after a plate appearance.

So, at the beginning of an inning, the baseball base/out automaton is in a {Nobody on, 0 out} state. After the first plate appearance, you will be in one of five possible states:

{Runner on 1st, 0 out}

{Runner on 2nd, 0 out}

{Runner on 3rd, 0 out}

{Nobody on, 0 out} (Batter homered)

{Nobody on, 1 out}

You can’t, after the first appearance, reach a state where there are two runners on or two outs. You have to go to an intermediate state first. There are exactly 24 possible states you can have in this automaton. Each state in this automaton is a two dimensional {base, out} object. And from any of these 24 possible states, there are a limited, finite number of possible following states.

The “automaton” then, defines the what possible states can exist, and the rules by which you can move from one state to another.

Got it?

OK, now to the thing I believe without evidence: I believe that before any given pitch, the batter is in some sort of Prediction State for the next pitch. After each pitch, the batter then moves into a different Prediction State.

I don’t have a clear belief on exactly how many dimensions these Prediction States have. Maybe the Prediction State has three dimensions it:

1. Whether to swing

2. When to swing

3. Where to swing

Or maybe these Prediction States are much more complex, combining the above three states with specific kinds of pitches and movements and locations. It may be expressed by something like this, for example:

{60% expection of fastball, 30% changeup, 10% curve;

80% outside, 10% middle, 10% inside;

60% down, 30% middle, 10% up;

70% in the strike zone, 30% out of the strike zone}

and then if the pitcher throws you a fastball on the lower outside corner for a strike, perhaps you move to a state like this:

{70% fastball, 20% changeup, 10% curve;

85% outside, 8% middle, 7% inside;

70% down, 20% middle, 10% up;

75% in the strike zone, 25% out of the strike zone}

Or whatever. I don’t really know as what the parameters for these Prediction States should be. Is it {pitch type, in/out, up/down, movement/straight, fast/slow} or some other combination of pitch attributes? I don’t know.

And to what extent are these prediction automata more or less universal, or does each batter have his own unique automaton with its own unique rules? Again, I don’t know.

But I do know that if I were to build a technology for analyzing baseball, this is where I would begin, right at the core of the game, the engine that drives the sport: what pitch the batter is expecting from the pitcher, and what happens when the pitch he gets conforms or deviates from that expectation.

In order to unite the quantum and Newtonian versions of baseball analysis, the biophysical and the statistical, any Grand Unified Theory Of Everything Baseball must, in my belief, have some way to handle the Prediction State of the batter.

Belief Without Evidence #5: The quality of a pitch is a function of its speed, location, and movement, and also of the batter’s swing and prediction state

There are a few pitchers, like Aroldis Chapman, who can throw a pitch with such high-quality speed that the location, movement, and prediction state are rather irrelevant. And there are some, like Mariano Rivera, who have such a combination of high-quality location and movement that the speed and prediction state don’t matter much. With pitchers like that, the batter can predict perfectly what pitch he’s going to get, and still not hit it.

But most pitchers do not possess such a high-quality pitch that they can be predictable and get away with it at the Major League level. They need to manipulate the prediction state of the batter in order to succeed.

The less a batter is expecting a certain pitch, the less likely he is to make good contact. But pitching is not just a function of being unpredictable: the pitcher must balance what the Prediction State of the batter is and the batter’s ability to hit it, with his ability to also throw a pitch with good speed, location, and movement.

The complex nature of that 5-dimensional object ( {speed, location, movement, swing, prediction state} ) is what makes baseball so fascinating from pitch to pitch.

So for each pitch, the pitcher wants to:

1. Choose a pitch the batter is likely to predict incorrectly

2. Choose a pitch the pitcher is likely to throw with good speed, location, and movement

3. Choose a pitch which will result in a suboptimal swing path, resulting either in a miss or weak contact

4. Choose a pitch which, if not put in play, worsens the batter’s Prediction State for the next pitch

Belief Without Evidence #6: The quality of an at-bat is a 3-dimensional function

Those three dimensions being:

1. Getting a good pitch to hit

2. Hitting a ball hard when you do

3. Hitting a ball hard if you don’t.

A good pitch to hit is a pitch that (a) he is successfully predicting, and (b) he can get a good swing on. Whether he can get a good swing on a particular pitch depends on what his swing path is.

And again, there are two kinds of predictions: the automatic subconscious one where the batter just reacts to a pitch, and a conscious one where the batter decides beforehand to look for a certain pitch and ignore all others. And the count plays a big role whether the batter can take an approach to consciously look for a particular pitch, or whether he should (with two strikes especially) just let his subconscious react to whatever comes in there.

On the subconscious level, the more the pitcher keeps throwing the same pitch, the more the batter predicts that pitch accurately, and the more likely the batter is to hit that pitch. When pitchers talk about “establishing the inside fastball” for example, this is what they mean: to change the Prediction State in such a way that an inside fastball becomes part of the Prediction State, and thereby necessarily reduces the expectation of a different pitch in the future.

Just because a batter gets a pitch he is predicting, does not mean he will hit it. Most batters have some kind of hole in their swing. Some batters prefer high pitches, others low. Some are vulnerable inside, and others can’t hit the outside pitch well. Some can hit a fastball, but can’t time an offspeed pitch. Others have a slow bat speed and struggle with fastballs, but feast on the slower pitches.

So for each pitch, the batter wants to:

1. Predict a pitch correctly

2. Swing at a pitch that if it lets him approximate his optimal swing path

3. Take a pitch if it would cause a suboptimal swing path (unless 2 strikes in zone)

4. Take pitches out of the zone to move to a better Prediction State for the next pitch

5. If in a 2-strike situation, make contact (foul or fair) on a pitch in the zone

Belief Without Evidence #7: SQL-reliant GMs don’t value the third dimension of #6 enough

In a vast sea of unordered pitches from an unordered group of pitchers, you will get a randomly-distributed plethora of good pitches to hit, so the numbers will all work out in the end. So you acquire hitters based on these vast seas of data, ignoring what the batter does with difficult pitches to hit, because in the long run, they don’t matter much.

But against a good pitcher on a good day who does not give you a good pitch to hit, what do those batters do? Do they hit a ball hard if they don’t get a good pitch to hit?

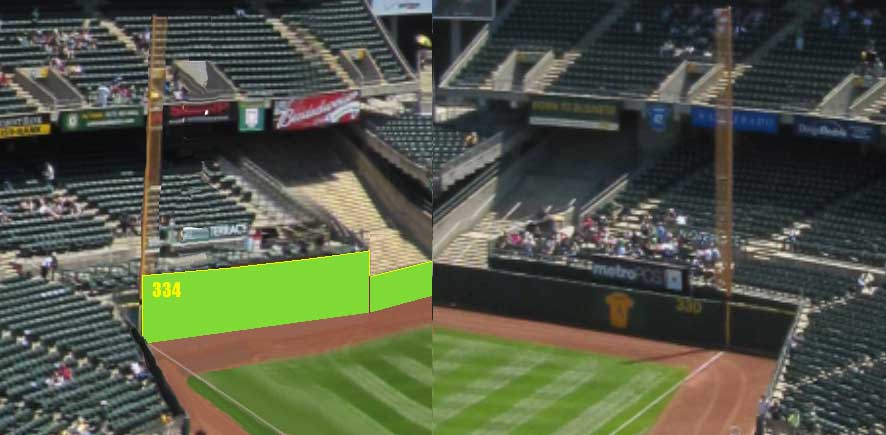

To me, the biggest difference between the A’s in the playoffs and the Giants in the playoffs is Pablo Sandoval. Because there may not be anyone in baseball right now better than Sandoval who does damage even when he does not get a good pitch to hit. He can turn pitches in the dirt, in his eyes, and/or six inches off the plate into a hit. He’s almost immune to prediction state manipulation by opposing pitchers. And Hunter Pence, though not as extreme as Sandoval, has similar characteristics.

The A’s simply do not pursue those types of players. Players like Sandoval tend to have low OBPs, because they swing at so many bad pitches. Minor leaguers with that profile flop far more than they succeed, so they’re a bad risk to take. But there are times, against a good pitcher on a good day who is simply not giving hitters a good pitch to hit, that it is valuable to have a player who often does damage even with a bad pitch to hit. And those times happen more often in the playoffs.

A technology that used a system of evaluating players in which high-level statistics of player value were derived from a low-level {speed, location, movement, swing path, prediction state} matrix would better identify the true value of such players.

Belief Without Evidence #8: Diversity is Good for Batting Lineups

This belief is related to the belief about the definition of the quality of a pitch, and to the belief of a biomechanical/psychological foundation to all of this. A lineup with too many batters with similar strengths and weaknesses can make it easier for a pitcher to settle into a psychological/mechanical rhythm and mow down such a lineup. A lineup that is diverse (some hit fastballs, some like it inside, or low, some slug, others make contact, etc.) makes a pitcher have to change his approach from at-bat to at-bat. That forces the pitcher to have to make a variety of quality pitches in order to win. It’s harder for a pitcher to win if he has to have multiple pitches working well.

So when I praised the Giants for having Pablo Sandoval, I did not mean that an entire team of hitters like Pablo Sandoval would be ideal. But having one or two guys like him in a lineup with some more patient-type hitters is a good thing.

Belief Without Evidence #9: A lineup without holes scores runs exponentially, not linearly

This is probably the easiest of my hypotheses to disprove. But I have the gut feeling that one guy who is an automatic out in the middle of a lineup can take a rally that might score five runs and drop that rally down to 0 or 1 runs.

I think we saw this play out with the 2014 Oakland A’s. At the beginning of the year, everyone in the lineup was healthy and hitting somewhat near or above expectations. The A’s were just killing it in the pythagorean win column, because they’d get a rally going and that rally would just keep going and going.

But then Josh Donaldson and Brandon Moss started having some nagging injuries, and Moss in particular became pretty much an automatic out for a month or two. Those five-run rallies, once plentiful, almost instantly disappeared. Every rally seemed to be killed by a terrible at-bat in the middle of it.

Almost every team has a hole in the lineup at any given time, someone who is slumping for whatever reason. So for most teams, run scoring appears to be linear. But in those rare cases when everyone is clicking at the same time, their run scoring graph turns like a hockey stick and shoots upward.

The A’s success early in the year depended on the lineup being holeless, and when holes appeared, the whole thing collapsed back from exponential scoring into linear.

Belief Without Evidence #10: A’s fans are magical elves

I’ve been playing in my mind lately with the idea that A’s fans are like the house elves in the Harry Potter stories.

We exist so that others may abuse us. The greatest triumphs of others often comes at our expense. We dress in ratty clothing (stadium). Yet despite this constant abuse, we are fiercely loyal to our master. We attack viciously anyone who dares attack our master. We perform magic (great stadium atmosphere) on their behalf, no matter how awful our masters treat us in return.

If ever we were given clothing (a new stadium) by our master, we would be free of our bondage. Some, like Dobby, desire this, but others would not know what to do with themselves with freedom and wealth. It would ruin the very essence of their being.

I used to be like Dobby, longing for the freedom that a World Series victory and/or a new stadium would bring. But now, I am beginning to feel that the other elves are right — that it is wrong to support S.P.E.W. and long for something that would destroy who we are.

We are meant to suffer, so that other wizards may have their glories. We are elves. Let us be that we are and seek not to alter us.