What happens when a monoculture fragments?

* * *

Here’s the big question in politics these days: how do you explain Donald Trump? Sean Trende of RealClearPolitics has an interesting three part series on the question. Nate Silver presents three theories of his own. Scott Adams hypothesizes that Trump is a “master persuader“. David Axelrod surmises that voters are simply choosing the opposite of the last guy. Craig Calcaterra thinks it’s worse than all that, and we’re entering a new dark age.

Those are interesting ideas, I suppose, and maybe there’s some truth to them, I don’t know. But I want to throw another theory out there that I got, indirectly, while following the news of David Bowie’s death.

* * *

Bowie was very knowledgeable about music of course, but also visual arts, as well. There are a number of interviews of Bowie in the 1990s where he connects the history of visual arts in the early 20th century to what happened to music in the late 20th century, most notably an interview with Jeremy Paxman on BBC Newsnight back in 1999.

* * *

First, some background. Up until the mid-19th century, the visual arts were very much a monoculture. Basically, you were supposed to paint pictures that looked lifelike in one way or another. But the invention of photography about that time changed the nature of the visual arts. The value of realistic paintings came into question, and artist began to explore other purposes for painting besides just realism.

The result of that exploration was that the visual arts in the early 20th century ended up splitting up into multiple subgenres like impressionism, cubism, dadaism, surrealism, and abstract impressionism. Bowie said, “The breakthroughs in the early part of the century with people like Duchamp were so prescient in what they were doing and putting down. The idea [was] that the piece of work is not finished until the audience come to it, and add their own interpretation.”

Duchamp’s urinal is the prime example of what Bowie is talking about. Is this a work of art?

…especially since Marcel Duchamp and all that, the work is only one aspect of it. The work is never finished now until the viewer contributes himself. The art is always only half-finished. It’s never completed until there’s an audience for it. And then it’s the combination of the interpretation of the audience and the work itself. It’s that gray area in the middle is what the work is about.

The urinal by itself is not a work of art, Bowie suggested. It becomes a work of art when you react to it.

* * *

But why? Why would this become an artistic trend? Bowie suggested that this is the natural result of the breakup of monocultures. When there’s one dominant culture, artists can dictate what art is, and isn’t. But when there isn’t a single dominant culture, breaking through to the mainstream requires the artist to meet the audience halfway. Bowie claimed that the visual arts went through this process first, and it became a full-fledged force in music in the 1990s.

I think when you look back at, say, this last decade, there hasn’t really been one single entity, artist, or group, that have personified, or become the brand name for the nineties. It started to fade a bit in the eighties. In the seventies, there were still definite artists; in the sixties, there were the Beatles and Hendrix; in the fifties, there was Presley.

Now it’s subgroups, and genres. It’s hip-hop. It’s girl power. It’s a communal kind of thing. It’s about the community.

It’s becoming more and more about the audience. The point of having somebody who “led the forces” has disappeared because the vocabulary of rock is too well-known.

From my standpoint, being an artist, I like to see what the new construction is between artist and audience. There is a breakdown, personified, I think by the rave culture of the last few years. The audience is at least as important as whoever is playing at the rave. It’s almost like the artist is to accompany the audience and what the audience is doing. And that feeling is very much permeating music.

Bowie suggests that it wasn’t just music that this was happening to in the late 20th century, but to culture on a broader scale:

We, at the time, up until at least the mid-seventies, really felt that we were still living in the guise of a single and absolute created society, where there were known truths, and known lies, and there was no duplicity or pluralism about the things that we believed in. That started to break down rapidly in the seventies. And the idea of a duality in the way that we live…there are always two, three, four, five sides to every question. The singularity disappeared.

Bowie then went on to suggest that the Internet will go on to accelerate this cultural fragmentation in the 21st century:

And that, I believe, has produced just a medium as the Internet, which absolutely establishes and shows us that we are living in total fragmentation.

The actual context and the state of content is going to be so different from anything we can visage at the moment. Where the interplay between the user and the provider will be so in sympatico, it’s going to crush our ideas of what mediums are all about.

It’s happening in every form. […] That gray space in the middle is what the 21st century is going to be about.

Look then at the technologies that have launched since Bowie made these statements in 1999. Blogger launched the same year as that interview, in August of 1999. WordPress launched in 2003. Facebook in 2004. Twitter in 2006. What’s App in 2010. Snapchat in 2011. Technologies such as these, which give broadcast power to audiences, have become the dominant mediums of the 21st century. The audience has indeed become the mainstream provider of culture.

* * *

Bowie didn’t make any specific claims or predictions about politics in these 1999 statements. But we can look at his ideas and apply them to politics, and see if they apply there, as well. It would, after all, be strange if this process which has been happening for over a century in the general culture did not eventually make its way into politics, as well.

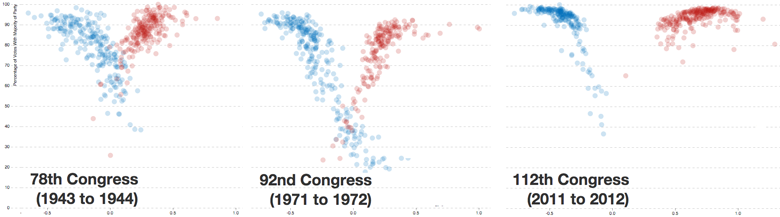

First, let’s ask, are we seeing any kind of fragmentation in our politics? (I’ll limit myself to American politics, because I don’t know enough about other countries to speak coherently.) It’s fairly obvious that the two American parties are more polarized than ever, but let’s show a chart to verify that. This is from the Brookings Institute:

As you can see, the parties were rather clustered together during World War II. In the 70s, you could see some separation happening, but there was still overlap. Now, they are two completely unrelated groups. So Bowie’s model holds in this case.

It could be argued that in the 2016 election, we are seeing a fragmentation of these two groups into further subgroups. On the Democratic side, there is a debate between the full-fledged socialism espoused by Bernie Sanders, and the more economically conservative wing of the Democratic Party represented by Hillary Clinton. (There do not seem to be candidates from the environmentalist/pacifist wings…yet.) On the Republican side, there are also clear factions now: the Evangelical wing led by Ted Cruz, the Libertarian wing led by Rand Paul, the more establishment Republicanism of Marco Rubio, Chris Christie and John Kasich, and the nationalism of Donald Trump.

These factions have always existed in the American political parties, of course. And there have always been subgenres in the arts and the general culture, too. But the difference this time seems to be that each faction is claiming, and insisting on, legitimacy. They are no longer satisfied with mere lip service from the party establishment. The days of the One Dominant Point of View are in the past.

* * *

Suppose that American political parties are indeed fragmenting. What kind of politicians succeed in that kind of environment?

The David Bowie theory would answer: politicians who possess the quality of allowing audiences to project their own interpretations onto them.

Whatever the policy differences between Barack Obama and Donald Trump, it’s hard to deny that both Trump and Obama possess that quality in spades.

The socialist and environmentalist and pacifist wings of the Democratic party seemed to project their fondest left-wing wishes onto Obama, even though his actual policy positions were rather centrist. As Obama’s presidency unfolded, these factions became disappointed, as reality set in. And likewise, in his Republican opponents there arose Obama Derangement Syndrome, where many right-wingers projected their worst fears of a far-left Presidency onto Obama, regardless of Obama’s actual positions.

Now we are seeing similar reactions to Donald Trump. The Republicans who are expected to vote for him are seeing him as a sort of savior to restore conservatism to prominence after a long series of losses in the Obama and Bill Clinton eras. This is despite the fact that, Trump’s immigration policies aside, Trump’s policy positions (that we know of), historically have been more consistent with establishment Democrats. And yet, many Democrats fear a Trump presidency and threaten to move to Canada if it happens.

So there are benefits and drawbacks to this “gray space” strategy. When you give the audience the freedom to add their interpretations to you, you may not like their interpretation very much. There was some pretty strong hatred of Duchamp’s urinal as a work of art. Others see that as part of its brilliance. Similarly, Obama and Trump can’t really control the large amount of people who react to them with repulsion. But it goes hand in hand with their success. That’s what the strategy does.

How do Obama and Trump accomplish this? What are the elements that allows them to interact in that “gray space”, when other politicians don’t? A few guesses:

- Be vague. Adhering to the specific policy proposals of a faction boxes you into that faction. It doesn’t allow room for other factions to meet you in the “gray space” between your factions.

- Be emotional. Obama and Trump know how to give speeches that rile up the emotions in the audience. You have to give the audience something to connect to, if it isn’t your actual policy positions.

- Step out from political clichếs. Bowie noted that by the 1990s, the standard three-cord rock-and-roll vocabulary had become too well-known to be a source of rebellion anymore. Similarly, the standard vocabulary of the Democratic and Republican parties have also become too well-known these days. The mediocre candidates these days seem to spend too much energy signaling that they know the Standard Vocabulary. We pretty much know what these politicians’ answers are going to be every question before they open their mouths to answer them. Hillary Clinton is a master of the vocabulary, but many people seem to be tired of it. Hence this article: “Hillary, can you excite us?”

How do you defeat such candidates? I don’t know, but it probably involves forcing them to be specific, to peg them as being trapped inside one particular faction or another. To reduce the “gray space” between them and the audience. Good luck with that. Should be interesting to watch as the primary season begins. Start your engines.

* * *

Postscript: Here’s the entirety of the David Bowie interview with Jeremy Paxman: