As Apple announces the iPhone 5 today, I want to make a confession. It’s a bit embarrassing for someone like me who has spent his career in high tech, but here goes: I don’t have a cell phone.

At first, my reason was this: I lived and worked and played on a very flat island with no tall buildings, so coverage was awful. I had reception in only one room of my house, not at all in my office three blocks away, and spotty reception where I play indoor soccer. I spent 95% of my time at those three places, and I wouldn’t be getting what I was paying for. When I went out somewhere that coverage was better, I’d borrow my wife’s cheap pay-as-you-go phone, and my needs were met.

The cell phone service providers made a mistake. They gave me an opportunity to learn that I could live without them.

* * *

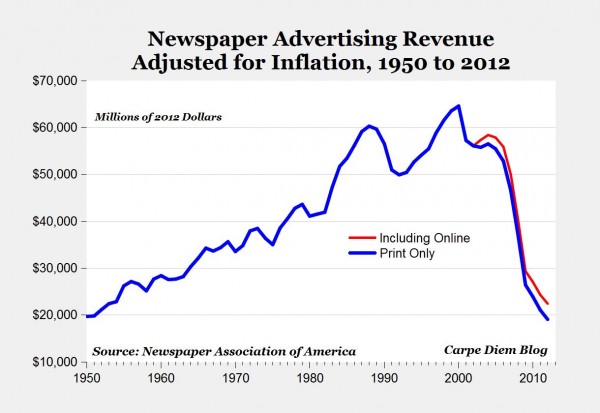

This is the image of an industry suddenly collapsing.

Why did the newspaper industry suddenly collapse like that? Because it got hit from two sides at once by the Internet. Craigslist and eBay took away their classified ad business, while blogs and online news sources directed their readership elsewhere for the same information. Newspapers might have been able to handle a one-front battle, but a two-front battle was catastrophic.

But there’s something else that hurt the newspaper industry: the indirect nature of their feedback loop. It’s a business model that provides a service to one group of people, while taking money from a different group of people.

The best kind of feedback for a business is revenue. If your revenue increases or decreases, you’re going to notice. But when the users of your product aren’t providing the revenue for your product, your feedback loop has a natural delay to it. The people who give you revenue might lead you to innovate (or not) in a direction your users won’t like, and you won’t notice that you’re making a mistake because it takes a while for that problem to reach your bottom line. So you react too slowly, and that slowness can be fatal.

* * *

In fact, all businesses that rely on advertising have this problem. Their users want one thing, and the revenue generators want something different. So if a company like Facebook starts alienating their customers in an effort to maximize their revenues, they may find themselves not just the subject of an Onion parody, but ruining their business before the bottom line has time to let them know they’ve made a mistake.

* * *

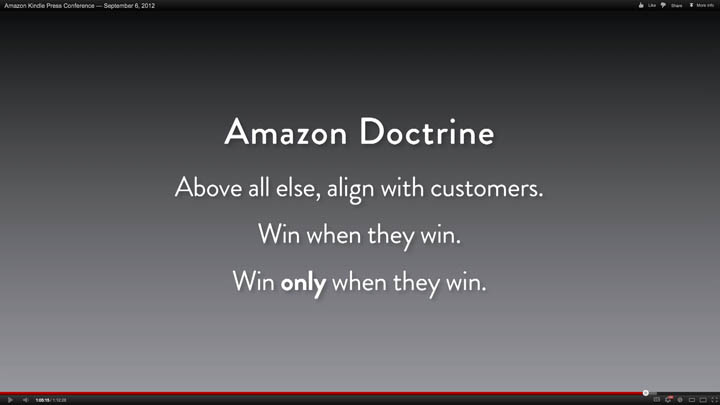

Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos is a very smart man. He understands this problem. He knows that the key to keeping ahead of the rapid pace of high-tech change is to master the feedback loop between what his customers want next, and what his company makes next. That’s why in his Kindle press conference last week, he laid out this doctrine:

Think about the major players in high tech right now: Microsoft, Google, Facebook, Twitter, Amazon, Apple. Which of these has their revenues most directly aligned with what their customers want? It’s probably in roughly this order:

Amazon/Apple

(gap)

Microsoft

(gap)

Google

(gap)

Twitter/Facebook.

Amazon and Apple sell most of their products directly to their users. When their customers buy something they make, they know the product is good; when they don’t buy, they know immediately they made a mistake. Microsoft doesn’t sell directly to users– they sell to distributors and OEM manufacturers, so there’s noise injected into their feedback loop, and they land just a little lower on this spectrum. Google sells ads, but their ads are often directly related to what the customer wants; if someone is searching for jeans, they get an ad for jeans. Sometimes the ad happens to be exactly what the user wants.

Twitter and Facebook, on the other hand, need to inject their ads into an environment where the users wouldn’t really want to see ads at all if they didn’t have to. This leads to customer dissatisfaction, expressed not just in the Onion parody above, but also in a real-life alternative social networks like App.net who are trying to sell directly to users.

* * *

My favorite product of all is probably Major League Baseball. I consume a lot of Major League Baseball. But MLB is going in a very tempting, but dangerous direction. When MLB began, a vast majority of their revenues came from the product their users consume. They sold tickets to the games, and that’s how they made their money. But more and more of MLB’s revenues are coming from indirect sources.

At a local level, if you’re a team like the Oakland A’s, who play in an antiquated stadium that doesn’t generate a lot of revenues, a big proportion of your money comes from TV and league-wide revenue sharing. So you can do things over a number of years, like threaten to move away and trade away favorite players, that damage your brand but aren’t directly noticeable in your bottom line. Ownership may not even know how much their fans hate them, because their loyalty to their local team keeps them around despite their dissatisfaction. But eventually, there may be a straw that breaks the camel’s back. Los Angeles Dodger fans may have hated owner Frank McCourt for years, but it was only in the last year of his tenure that the dissatisfaction actually became truly noticeable in attendance figures. The feedback loop in baseball has quite a long delay.

In recent years, baseball’s misalignment problem has accelerated almost exponentially. Like the newspaper industry, the source of this change is new technology. Unlike the newspaper industry, however, the change has caused MLB’s revenues to increase, not decrease, dramatically.

The reason for this change is twofold:

- The DVR allows people to skip through commercials on TV. This makes live events, which people can’t skip through, a much more valuable delivery mechanism for advertising.

- Internet video allows people to watch television shows and movies without subscribing to any sort of cable or satellite TV service. Cable/satellite may or may not be shedding customers at the moment, but it’s certainly not growing much, and without sports would almost certainly be shrinking. This makes sports networks extremely important to cable and satellite providers: without them, most people will eventually learn to do without cable TV, and just get all their content from the Internet.

So this sets up a strange mismatch between what MLB customers want, and what their revenues tell them to do. MLB fans want to watch their favorite team on whatever device they prefer. But MLB’s revenue stream is depending more and more on their customers NOT being able to watch their team over the internet, forcing them to watch on TV.

MLB’s revenues come less and less directly from baseball fans, and more and more indirectly, from TV networks and cable/satellite providers.

This causes MLB to lose control over the customer experience of their fans. If a TV network and a cable provider can’t come to an agreement on price, for example, Padres fans can go a whole season without being able to watch their team on TV. And if not all TV networks are available on all cable/satellite services, fans have to scramble around to watch the games they want.

Or, fans just go without. And what does that do? It ends up teaching them that they can learn to live without your product. That too, may not be noticeable right away, until it snowballs too late for you to do anything about it.

* * *

But you can’t really blame MLB, can you? If you’re the Los Angeles Angels and someone wants to pay you $3 billion dollars over 20 years for your TV rights, do you turn that down? No, probably not.

In expectation of an even larger payday than the Angels got, the Los Angeles Dodgers recently sold for $2.1 billion. Given that the estimated value of the Dodgers just a year before that was about $800 million, over 60% of the value of the franchise lies in that regional TV deal.

But think about that for a second. The new owners of the Dodgers spent $1.3 billion dollars on a business model that:

(a) depends almost entirely on another industry that isn’t growing, and would be in steep, steep decline without your industry. If either one of your industries catches a cold, the other one will necessarily start sneezing.

(b) puts your industry in a complete misalignment with your customers, requiring you to prevent your customers from consuming your product in the way they’d prefer, distancing yourself from the revenue feedback loop, making it more difficult to know if you’re doing any long-term damage to your product, and where you need to improve.

The new Dodger owners obviously didn’t care. Maybe they didn’t think about these risks. Or maybe they did, and thought the math worked anyway. Or maybe they considered it, but they thought they could sell the team to someone else before the whole house of cards fell in, like an investor in a Ponzi scheme who doesn’t think he’ll be the one who ends up being the victim.

Who knows. But me, I wouldn’t touch a business model like that with a 10-mile pole.