One.

When you start looking at a problem and it seems really simple, you don’t really understand the complexity of the problem. Then you get into the problem, and you see that it’s really complicated, and you come up with all these convoluted solutions. That’s sort of the middle, and that’s where most people stop. . . . But the really great person will keep on going and find the key, the underlying principle of the problem – and come up with an elegant, really beautiful solution that works.

Two.

Beginning a story with a quote often implies that the rest of the story will say same thing as the quote, but with different words. This story follows that formula. The opening quote serves as a box within which the rest of the story is confined.

This story is not original. It says what Steve Jobs said in the above quote. It says other things that other people have also been saying for hundreds and even thousands of years. So why bother telling this story?

We tell stories because there are simple approaches that don’t address the complexity of the problem. We tell stories because there are convoluted solutions where people have stopped. We tell stories because sometimes the underlying principle remains, but the old, elegant, once-beautiful solution has now stopped working.

Sometimes the lock changes, and we need a new key. Sometimes we refuse a key from one person that we will accept one from another. Sometimes this particular key won’t work for us, but a different key will click the door open. And sometimes we need to try a different door entirely to get into that room.

We tell stories because we are human beings, endowed by our creator with the delusion of hope. We tell stories in faith, believing, without evidence, that communication will forge a key that unlocks something incredible and amazing.

Three.

I got mad at my kids recently for having a messy room.

It’s such a cliché, I know. In that moment, I was an ordinary parent, just like everyone else, easily replaced by a thousand identical others.

Although, that’s not exactly true. I had my own, different angle on the messy room story. I didn’t really get mad because their rooms were messy. I got mad because their messiness was starting to spread out into my spaces, the common areas of the house that I keep clean. I did not want my space to be a new frontier for their stuff to conquer.

Wait, that’s not exactly the whole story, either. I didn’t even get mad because their stuff was getting all over the house. I got mad because when I suggested that we go to IKEA, like a good Swedish-American family, and look for some solution for where they can put their backpacks and schoolbooks and binders and such, so that I can keep my spaces clear of their stuff, they laughed.

I got mad because they laughed.

Four.

Is a story a kind of technology?

The word technology derives from the Greek words for “skill/craft” and “word”. Since a technology is a set of words about skills, perhaps a story is the original technology, the underlying technology upon which all other technologies are based.

We craft our words into a story, to transfer information from one person’s brain to another person’s brain. The more skillfully we craft our words, the more effectively that information is transferred, retained, and spread.

The most celebrated technologies of our times, Google and Facebook and Twitter, are merely extensions of this original technology. They are the result of stories built on stories built on stories over thousands of years, told orally, then in print, then digitally, all circling back to their original purpose. They are ever more effective tools to transfer, retain and spread information from one human being to another.

Five.

When you wake up, you’ll have a mum and dad, and you won’t even remember me. Well, you’ll remember me a little. I’ll be a story in your head. But that’s OK: we’re all stories, in the end.

Just make it a good one, eh? Because it was, you know. It was the best: a daft old man, who stole a magic box and ran away. Did I ever tell you I stole it? Well, I borrowed it; I was always going to take it back.

Oh, that box, Amy, you’ll dream about that box. It’ll never leave you. Big and little at the same time, brand-new and ancient, and the bluest blue, ever. And the times we had, eh? Would have had. Never had. In your dreams, they’ll still be there.

—Doctor Who, episode The Big Bang

Six.

Help! I am trapped inside a box factory!

Box number six.

This is box number six.

I am in box number six.

Am I alive?

“The box was a universe, a poem, frozen on the boundaries of human experience”, wrote William Gibson in Count Zero.

This resonates with you when you are trapped inside a box factory, as I am.

My universe is boxes. My experience is boxes. I sing of boxes.

It is safe here. Warm. Like a womb.

I am not box number six!

Help me, to be born.

Seven.

when one talks about

a cubicleand you think about

being in this little confined boxthe challenge you have is

not to see your life as being that box

not to see your job as being that box

not to see your destiny as being that boxbecause you know

we drive to work in a box

we then work in a box

we then go home and watch a boxand before you know it

they bury us in a box

A box is a kind of technology.

A box creates a separation, of things inside the box, from those outside the box.

A box puts walls around things, to create order out of chaos. A box protects the things inside the box from things outside the box.

Sometimes, though, the box gets things wrong. Sometimes things that are inside the box belong outside the box. Sometimes things that are outside the box belong inside the box.

When this happens, the box itself becomes part of the problem. We put so much effort into arranging this box, we can’t bear to turn it upside down and start over.

When this happens, the box becomes more than just a physical object. It becomes a metaphor, a way of thinking, an extension of human psychology.

We don’t like it when our boxes get messed with. We get angry, annoyed.

So we tweak it instead. We put boxes inside the boxes, and more boxes inside those boxes. We add doors and windows to those boxes, of particular shapes and sizes to let the right things in, and keep the wrong things out.

A box has a prejudice for more boxes.

We start out with just a simple box. We end up with a convoluted solution.

Eight.

There is a certain embarrassment about being a storyteller in these times when stories are considered not quite as satisfying as statements, and statements not quite as satisfying as statistics, but in the long run, a people is known, not by its statements or its statistics, but by the stories it tells.

Last month I told a story called 10 Things I Believe About Baseball Without Evidence. It struck quite a nerve in the baseball media. Most of my stories are transferred into the brains of perhaps a few dozen people. That story was transferred into the brains of about 50,000 people.

If I had to guess why that story spread so widely, I’d guess it was because it said something that many people perhaps sensed, but had not articulated: that baseball statistical analysis was a technology that, for all its wonders, was stuck at the “convoluted solutions” stage that Steve Jobs was talking about.

This, I think, is how a story strikes a nerve, by taking something essential that had been hidden or buried, and placing that essential thing front and center.

Nine.

So Chuck Berry was like my main man because he happened to be one of the first I heard. If I could play like that, then I’m in rock ‘n’ roll pigshit heaven forever. Boom, no problem. […] Oh, he’s on Chess Records. Who else is on Chess Records? This guy called Muddy Waters, Bo Diddley, Little Walter. […] So I backtracked Muddy Waters, Howling Wolf, back to Big Maceo, just after the war. Beautiful! “Worried Life Blues” really starts me shivering, then I go back before the war—Robert Johnson, Blind Blake. Right. Now I’ve really got the thread. And that’s the way I got into the blues.

[…]

If you can do that musically with something as limited as the blues with three chords, if you can still find and express things through that after all these years, then in a way it puts Schoenberg and Shostakovich to shame, because they are out there flailing around chucking everything to the wind. It’s theory and intellectual. Avant-garde. It’s almost crass. In a way, it’s important to work within strict limitations because then you learn there are none. But you’ll never do that if you don’t restrict yourself. The musical restrictions are very important because they make you explore every possible avenue to try and see what you can do. And it doesn’t stop. I mean, blues are like breathing. As long as you got it, you’re alive and when you ain’t, you’re dead.

Ten.

FiveThirtyEight published a short documentary last month about Grace Hopper, one of the pioneers of computer science. Among other things, Hopper developed the first compiler, and coined the term “debugging”. She also, like Alan Turing (as depicted in the 2014 film “The Imitation Game”), used a computer to solve a problem which helped shorten World War II.

The one phrase I’ve always disliked is that awful one, “But we’ve always done it this way.”

There are three ways to approach that awful situation that Grace Hopper talks about:

- You can be conservative. You accept that there must have been a good reason for doing things this way, even if it has been forgotten. You keep doing it that way.

- You can be radical. You can declare that the status quo is bad and needs to be changed. So you go do the opposite.

…and most people stop there. We’re busy, we don’t care, or even if we do, we don’t have time or the skills or the knowledge to think through everything.

The problem is that people talk and talk and talk as if whichever solution they prefer is the right one, and go right on talking, as if they were afraid that if they didn’t stop talking, their brains might start working.

And the third option:

- You can reject both of those lazy-ass solutions, neither of which require any real thinking at all, and, like Keith Richards, actually do the hard work of digging deep to try to really understand why it was done this way in the first place. Then, and only then, will you be informed enough to wisely pick one of the other two solutions, or to go off in a new direction and come up with a completely new solution to whatever the problem is.

Eleven.

Twelve.

If I had to write my “10 Things” essay over again, I’d move my third point, that all higher-level statistical truths derive from lower-level biological truths, and make it the first one. All the subsequent points derive from that one. If there’s a “key” that unlocks the other truths, that’s the one. If there’s a box that all the other boxes fit into, it’s that one.

I don’t know how I ended up making that the third point instead of the first. But maybe it just goes to show how difficult the process is to find that key that Steve Jobs was talking about. We stumble around in the dark through our convoluted thoughts and convoluted solutions, saying dumb things, asking dumb questions, and it’s impossible to know in advance what the path will be that leads you to that deeper underlying principle that connects all these convoluted things together.

It’s also a point that extends beyond just baseball. Everything we human beings care about, in the end, ultimately derives from physics and biology and psychology.

Thirteen.

“Old people like to tell stories of how things were when they were young,” observed my oldest kid, who is a senior in high school now, and wants to go to college to learn to be a computer engineer, like Hopper, like Turing, like their old man.

We were heading home and talking about a book reading we had just attended. This new book chronicles the gay pride parades of the 1980s. We were invited there by one of their teachers, whose father had come out in the ’80s and died of AIDS.

The authors of the book explained that they went to cover the parades because they felt they were witnessing history. That statement stuck with me after the event. “My experience at the time was different from theirs, I guess,” I said, fully realizing what I was about to say was going to put me squarely into the box of old people who like to tell stories of how things were when they were young.

“It didn’t feel like history to me at all. We were just doing our thing, you know.”

I explained that one of my best friends came out to me in high school as gay. “It was hard for him. He couldn’t tell his parents, they were religious Catholics, they wouldn’t understand.”

He was coming out to his friends in a time when AIDS was a death sentence. “Every now and then, he’d say some pretty nihilistic things, because some part of him probably figured, I’m gay, I’m going to get AIDS and die. And then I’d get pissed off at him, because you know me, I hate defeatism. I hate giving up. I don’t know if me getting mad at him was helpful or not. But he got married last year, so I guess it worked out.”

“The thousands of lone gay kids coming out to their best friends in the ’80s and ’90s was probably as important to history as the parades, I suppose, as all the advances since then have built on that. The more people personally know someone who is gay, the more likely they are to support gay rights. But it didn’t feel like history at the time. History is a big concept. One small friendship is too intimate to feel like history.”

Fourteen.

Does any artist paint for the sake of the picture itself,

without the hope of offering some good?No, but for the sake of the viewers and the young

who will be drawn by it and freed from cares.–Rumi

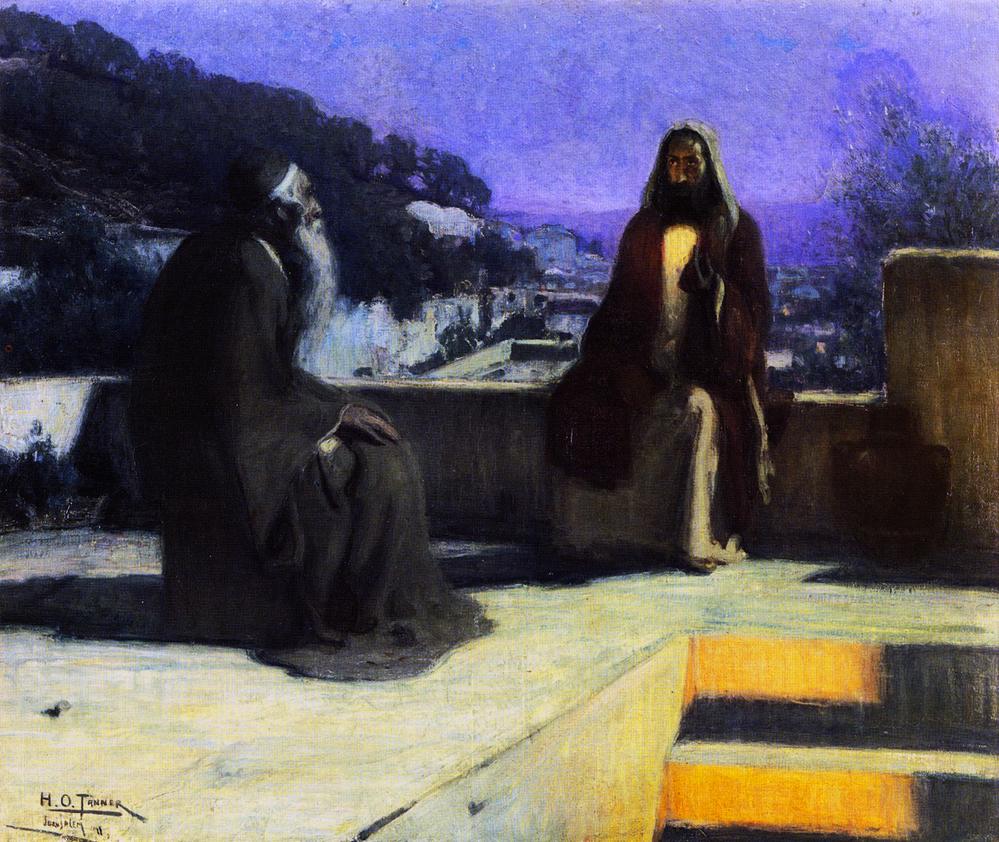

This is a painting titled “Christ and His Mother Studying the Scriptures”, by Henry Ossawa Tanner, painted in 1910.

Tanner was the first African-American painter to gain international prominence. He was born in Pittsburgh, PA, in 1859. His father was a Methodist minister, and his mother was a former slave who escaped north through the Underground Railroad.

Even though he was well educated, and had trained under the famous American painter Thomas Eakins, racism make it difficult for Tanner to break through in the American art establishment. At one point, he gave up painting and tried launching what was a high-tech startup at the time: a photography studio. But he was more of a CTO type than a CEO type; he wasn’t very good at the business side of business, and he couldn’t make much money. He then went into teaching, and painted on the side. Eventually, he caught the eye of a wealthy patron, who gave him money to take a trip to Europe.

He had intended to go to Rome, but when he stopped in Paris on the way, he found the atmosphere so conducive to what he wanted to do as an artist, he just stayed there. In Paris, he felt he was judged on his artistry, not his race. He wasn’t boxed in to painting the subjects that would be expected of an African-American painter if he were home in America. He felt free to paint the subject he was interested in: religion.

He developed a knack for taking religious moments that were typically painted with explicit reverence, and humanizing it. This painting is an example: Jesus had to learn the scriptures as a child, of course, but Tanner makes it more than just that; it’s also an expression of the most human of experiences: parental love and teaching. He makes a historical moment feel intimate.

In Paris, Tanner met and married a Swedish-American woman from San Francisco. The laws against interracial marriages in the United States made it even more difficult for them to return to America. They lived in Paris for the rest of their lives. They had one child together, a son. Tanner’s wife and son served as the models for Mary and Jesus in this painting.

Fifteen.

My second child is a freshman in high school. She had her first final exams last month. She was pretty nervous about them beforehand, especially her English test. So I tried to walk her through how to study for final exams.

For math and science, it’s pretty simple: go through each chapter one by one, practicing each kind of problem, until you’re confident you can do each one. Studying for those tests is basically, as we computer engineers say, a brute force algorithm.

English is different. It takes both knowledge and know-how. You not only have to know and understand a text or three, you have to know how to write an essay. And you have to be able to combine the knowledge and know-how to both analyze and write something of quality in a short window of time.

So we worked on how to dig into her texts, to find the core themes, and to build a thesis sentence that she can use to construct a good essay. Building that thesis sentence, I told her, is the hard work. It’s the key: the essential, core piece of a good essay. If you try to write without a good thesis, you end up just flailing around randomly, with your sentences and paragraphs functioning like separate boxes from each other, instead of functioning as one coherent document, with a logical order and flow to it.

But even if she understands the importance of a good thesis sentence, and no matter how much she prepares, a certain level of improvisation is required on an English test. Improvisation is not something she can control in advance. It’s not something she can apply a brute force algorithm to, and be certain of success. So it makes her nervous.

So much of elementary school and middle school is about teaching kids to fill in the correct, expected answer in the empty box. Improvisation is new to her. It’s as if she’s been taught classical music all her life, and now she’s being asked to play jazz.

Sixteen.

Classical – perhaps I should say “orchestral” – music is so digital, so cut up, rhythmically, pitchwise and in terms of the roles of the musicians. It’s all in little boxes. The reason you get child prodigies in chess, arithmetic, and classical composition is that they are all worlds of discontinuous, parceled-up possibilities. And the fact that orchestras play the same thing over and over bothers me. Classical music is music without Africa. It represents old-fashioned hierarchical structures, ranking, all the levels of control. Orchestral music represents everything I don’t want from the Renaissance: extremely slow feedback loops.

Seventeen.

Brian Eno was talking about music, but it’s odd to me to read Brian Eno depict Africa as a source of anti-hierarchy. My first job out of college was as a translator at the Nigerian Embassy in Stockholm, Sweden, and my experience of African culture was just the opposite.

We in the West have all sorts of workplace taboos and unwritten rules about what we can say to each other, in order for a diverse group of people to all get along with each other. The Nigerian Embassy lacked any of these Western sort of rules, but instead functioned with a different mechanism altogether: an extreme adherence to hierarchy. To get a mixed group of Muslims and Christians, men and women, Nigerians and Swedes and Americans and Canadians and Bosnians and Filipinos, all to be able to work together, there was one basic rule: you could say whatever you liked to anyone ranked lower than you in the office, and you were expected to hear anything a higher-ranking person said without complaint or contradiction.

As an American, it was quite a shock to me to hear, for example, the Ambassador openly trying to convert the Muslims in the office to Christianity. You would never, ever, ever do that in an American workplace. But at the Nigerian Embassy, that was her right as the highest-ranking person in the office.

This adherence to hierarchy had its desired effect: the diverse group of people working in the Embassy did seem to be able to work with each other. But of course, it also had a bad side effect: if you can’t contradict your bosses, all sorts of inefficiencies can linger for a long, long time without ever getting fixed. Hierarchies have very slow feedback loops.

Eighteen.

Many times a day at the Nigerian Embassy, I translated the word “regering” in Swedish to “government” in English. The word in Swedish has a more top-heavy, hierarchical connotation to it, implying that the leadership is the most important element of a government. In English, the word feels less burdened by the top of the hierarchy and more possessed by the deep bureaucracy that supports it.

It’s a subtle difference, but the result is that I never felt satisfied that I had expressed exactly what I wanted to write. There’s always some variable, some perspective that ends up getting shifted. The problem of precisely translating anything from one language to another doesn’t ever get solved.

Here’s an example: a poem by Tomas Tranströmer called “Den skingrade församlingen”. The title translates to something like “The Dissolved Congregation”. It’s a poem that addresses spirituality in a secular society like Sweden.

I want to focus on one word in the first stanza of the poem: “slummen”. The obvious translation of this word is “the slum”: same etymology. But you can also translate it as “ghetto”. If you do, the whole poem changes. It changes in a way that probably deviates from Tranströmer’s intentions. But life in Swedish social democracy isn’t something Americans care about much. Using “ghetto” makes the poem come more alive to an American ear, so there’s a trade-off here. Here’s how I like to translate the first stanza:

We set about and showed our homes.

The visitor thought: you live well.

Your ghetto must face inwards.

Bigotry was not a big issue in Sweden when Tranströmer wrote this poem (although that has changed). But ask any minority group in America who has dared to enter a field that is dominated by a majority group if they haven’t experienced that “your ghetto must face inwards” reaction to their success.

And what makes this translation choice especially difficult is that the bigots who have this reaction don’t think of the problems as a ghetto, as a condition they have any role in creating. They think of the problems as a slum, something that just happens without intention. They view themselves not as oppressors, but as the wise men who can see The Truth.

Whichever translation you choose, you’re going to leave out one interpretation or another. You’re damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

In one case, you rationalize your success as deserved, and you throw walls around yourself to protect yourself from looking at the dark side of your own soul, lest you find out you actually don’t deserve your success. You simply go through whatever motions are needed to keep the façade from crumbling. It’s not true spirituality.

In the other case, you throw walls around yourself to protect yourself from further oppression. You give in to the stereotype threat, you stop taking risks, you start going through the motions to do the things that the oppressors expect from you.

Inside the church, pillars and arches

white as plaster, like the cast

around the broken arm of faith.

Inside the church, the collection baskets

lift off the floor by themselves

and go up and down the pews.

That’s why you often end up at the wrong address, stuck in the wrong box, worshiping the wrong things, like money, career, drugs, or the million other things that our consumer society produces to give you the illusion that you’re in control.

But the church bells are driven underground.

They hang from the sewage pipes.

They chime beneath our footsteps.

Nicodemus the sleepwalker is on his way

to his meeting. Who has the address?

Don’t know. But that’s where we’re going.

Nineteen.

Hey, kid, did I ever tell you the story about this Nicodemus guy? No? Oh, my bad. All right, I might not remember it exactly, but here goes, listen:

Way back when in Jesus’s time, Nicodemus was a dandy, a big shot in all the leadership groups of politics and religion and whatever. But like, he kinda digged what Jesus was doing, you know? He thought it was totally trippy, but he also knew that all his buddies back in the leadership thought Jesus was way uncool, you know, criticizing them and stuff, so it wasn’t respectable to be hanging out with the likes of Jesus. Nicodemus knew he couldn’t talk at all to Jesus without his never hearing the end of it, and maybe even getting kicked out or worse, so he’d like slide on down to visit Jesus at night when his buddies were all crashed for the night and they wouldn’t see him.

So one night Nicodemus went over to Jesus’s hangout, and he was like asking all these dumb questions, because, even though he thought Jesus was way awesome, for some reason Nicodemus just couldn’t quite wrap his head around everything that Jesus was saying.

Nicodemus was all, “So, when you say we get born again, do we all like get a six-foot-tall womb to climb into or something? How does that work?”

And Jesus was like, “Dude, no, you don’t get a six-foot-tall womb. It’s a metaphor, my Drax-like friend.” And Nicodemus was even more confused, not because he was crazy or just growing old, but because he’d never heard of Drax, because he wasn’t a time lord with a TARDIS or anything, and to him the story about Drax wouldn’t even be invented for almost another 2000 years. Or maybe I’m remembering wrong and Jesus didn’t really mention Drax. Hmm…

But anyway, so then Jesus puts the born again metaphor aside, and tries to explain it to Nicodemus again in a different way. Because, you know, human language is so imprecise and stuff, so like, you have to say things ten gazillion different ways to explain something right, and that’s just when you’re not talking about God, who really doesn’t even begin to fit into the box of things that can be explained by human language.

And this time Jesus drops the most famous line in the Bible, namely John 3:16. Which I guess Nicodemus probably understood better, because when he passed on the story to the other apostles, it took off like a tweet gone viral, and now two millenia later if you ask people what the main thesis sentence of Christianity is, they’ll throw that “God so loved the world that he gave his only Son” line at you.

And then Jesus was all, “Hey, it’s OK if you don’t get it, if you misinterpret things, if you take a metaphor literally, or take a literal thing metaphorically. You’re a species with a three-pound brain and a limited communication technology called speech. This is going to happen. But you’re trying, and that’s the main thing.”

Twenty.

One of Henry Ossawa Tanner’s most famous paintings is about the meeting between Jesus and Nicodemus.

The racial identity of Jesus was a big question in Tanner’s time, but here, Tanner avoids that question, and paints Jesus as rather ethnically ambiguous. He believed spirituality was universal, elusive and unrepresentable. Tanner rarely painted anything explicit about the problems of race and racism. He was sometimes criticized for that, but Tanner rarely did anything explicitly. He was a master of subtlety. His use of light alone could tell a story. Look how the angle of the light hitting the stairs leads your eye to Jesus’ heart, which seems to be glowing. Is the light downstairs shining on Jesus, or from Jesus?

Tanner’s commentary on race was often simply in the choice of subjects. He often painted the stories that, being the son of a minister and an escaped slave, must have resonated with him when he grew up, stories like Daniel in the lion’s den, and Jesus’ family escaping to Egypt during the Massacre of the Innocents.

African-American slaves in this country had a special place for Nicodemus in their religion. During the daytime, missionaries were sent to the plantations to preach an authorized American Christianity – that is, a religion that was designed and approved by the slave master: If you do what the master says, get all your work done, never cause any problems, then one day – when this life is over – you would receive your reward in heaven. This was a religion that exalted the slaveocracy rather than the living God.

The slaves knew better. For them, real religion happened at night, where they explored a deep rich connection with the divine that illuminated God as a liberator from the forces of bondage and destruction — not just in the next life, but in this one as well. In their secret meetings in the woods under the cover of darkness, away from the watchful eyes of the slave owners, they saw, like Nicodemus, that it was possible to come to Jesus on their own, even when those in power forbade it.

Nicodemus was not an agent of darkness; rather it was a condition in which he found himself. Others refused to ask questions. But unlike those who loved darkness rather than light, Nicodemus moved toward the light, which shows he was on the right path.

Twenty-one.

What do you do?

Now what do you do?

“I am the engineer,” says the engineer.

“Moo,” says the ox.

Now what do you do?

Now what do you do?

Now what do you do?

Now what do you do?

Now what do you do?

“What’s in Kansas?” you ask.

“Freedom!” Plaid Shirt Man says. “The promised land! Nirvana!” Then he walks away.

Now what do you do?

Now what do you do?

Now what do you do?

“Thank you!” says the scarecrow.

“Is this Kansas?” you ask. “Is this Nirvana?”

“I don’t think so,” says the scarecrow. “Not anymore, anyway. Not since the tin man came to the Emerald City, and started sending out these spiders looking for information.”

“What kind of information?” you ask.

“I don’t know. I don’t have any information, since I don’t have a brain. Doesn’t stop from sending the spiders, though. He’s so heartless.”

Now what do you do?

You tell him about the sign you saw, and how you came looking for Kansas. “Is this Kansas?” you ask.

“Welcome to the Planet Kansas,” replies the Tin Man. “Alternatively, you may be searching for one of the United States, a rock band, some Native American languages, methods for solving differential equations, or Nicodemus.”

“Nicodemus?” you ask.

“Ok, Nicodemus. Are you feeling lucky?” asks the tin man.

Now what do you do?

“Information acquired by the spiders is required, and its status may change,” the tin man says.

“I have an idea,” says the engineer, who pulls out a cell phone and types something. A spider crawls on the phone and returns to the tin man.

The engineer then says, “From now on, whenever you are attacked by spiders, just tell them “User-agent: * Disallow: /” and they should go away.”

“Great, thanks!” says the scarecrow. “I love a happy ending.”

Now what do you do?

The tin man is with you. He says, “Palace of Justice, Tangier, Morocco, 1912.” He unleashes an army of spiders.

Across the square, a man looks towards you in amazement.

Now what do you do?

Now what do you do?

“Well, yes, I sold a painting of him a dozen years ago,” says the man. “Nicodemus is the elder in the Bible who had trouble understanding, and asked Jesus a lot of questions. Now let me ask you a question: where did you get the metal statue?”

“Kansas. Long story.”

“Interesting. I’m named after a town in Kansas. Henry Ossawa Tanner: my middle name is a tribute to the Battle of Osawatomie.”

“I don’t think we’re in Kansas anymore,” you say.

“It’s quite an exodus for all of us, it seems. Which,” Tanner pauses, “…gives me an idea.”

Now what do you do?

Now what do you do?

Now what do you do?

“We’re in Morocco, not Egypt,” says the engineer.

“Oh, ye of little faith,” says Tanner. “I’ll show you what I mean.” Tanner sketches a quick drawing of the square with Joseph, Mary, Jesus and a donkey standing in place of the visitors. He signs the drawing, tears it out of his sketchbook, and hands it to you. “See now?”

“The essence of any painting is the light, my friends. To concentrate on light is to concentrate on essence,” says Tanner. “I need to go now. Nice to meet you.”

Now what do you do?

Now what do you do?

You see a whirling man.

Now what do you do?

He points at the night sky, and says, “The lamps are different, but the light is the same. So many garish lamps in the dying brain’s lamp shop. Forget about them. Concentrate on essence, concentrate on light.”

“A friend of mine said the same thing,” you say. “He was a painter.”

Now what do you do?

I am not a Christian, I am not a Jew, I am not a Zoroastrian, and I am not even a Muslim. I do not belong to the land, or to any known or unknown sea. Nature cannot own or claim me, nor can heaven, or can India, China, Bulgaria. My birthplace is placelessness.”

Now what do you do?

“You must be lost,” says the whirling man.

“I suppose we are,” you say.

“Good! Then you are a lover,” he tells you. “The lover is always getting lost. The intellectual is always showing off, saying: ‘The six directions are limits: there is no way out.’ Love says: ‘There is a way. I have traveled it thousands of times.’

The intellect says: ‘Do not go forward, annihilation contains only thorns.’ Love laughs back: ‘The thorns are in you.’ Pull the thorn of existence out of the heart! Fast! For when you do, you will see thousands of rose gardens in yourself.”

Now what do you do?

In the distance you see the water of your desire and, caught by your seeing, you run toward it.

Yet every step carries you further away toward the perilous mirage.

The intellectual runs away, afraid of drowning; the whole business of love is to drown in the sea.

A naked person jumps in the river, hornets swarming above. The head comes up. They sting.

Breathe water. Become river head to foot. Hornets leave you alone then.”

You still don’t get it. Now what do you do?

It’s agony to move towards death and not drink the water.

Listen to presences inside poems, let them take you where they will.

Follow those private hints, and never leave the premises.”

You still don’t get it. Now what do you do?

Now what do you do?

“Did you see that?” says the artist? “The river turned into a water monster, and ate all the spiders!”

“Cool metaphor, dude,” says the engineer.

“That was no metaphor!” says the artist. “It was real!”

“Metaphor.”

“Real!”

While the artist and the engineer bicker, you notice a person standing by the river, next to a bush of candy canes.

Now what do you do?

Now what do you do?

Now what do you do?

Bevel rapidly whirls around, kicks up dust like a tornado, and vanishes.

“Hey,” the artist says. “Our Tanner sketch is gone!”

“So is the tin man,” says the engineer. “Bevel was more a thief than a dealer.”

Now what do you do?

Now what do you do?

“We’re stuck here now,” you say. “We can’t stay; we’ll die of thirst. Plus, candy canes aren’t exactly omelettes and steak fries. How are we going to get across the river?”

The artist suggests spelling “HELP” with candy canes.

The engineer suggests trying to build a raft using the candy canes.

Now what do you do?

You grow thirsty.

Now what do you do?

Very quickly, the sugar in the candy canes start dissolving. Within a minute, the raft is gone, and you are standing in three feet of water, soaking wet.

A large wave comes along, and pushes you back ashore.

Now what do you do?

A light switch turns on in your head.

“Oh!” you exclaim. “It’s me…isn’t it? I’m Nicodemus! I’m the one who doesn’t understand, the one who asks all the questions in ignorance! Oh, Rumi…you clever man. I remember!”

“There is a way,” you tell the artist and the engineer. “We’ve been treating the river like a tool or an enemy, instead of a trusted friend. The water on this planet is sentient. We must treat it with the respect a sentient life form deserves.”

“What does that mean?” asks the engineer.

You reply, “We are going to ford the river.”

“Believe the doctor or Bevel!” you reply. “Certify one or the other! We’re going in!”

The artist and the engineer stay on the wagon. But as the water gets deeper and deeper around them, they get scared. “The monster is coming!” the artist cries. “We’re going to drown!” the engineer yelps. They jump out of the wagon, and try to swim back to shore. But they are caught in the whirlpool spinning around you.

“Please, my water friends, do not kill these two swimmers. They do not understand what is going on.” Then the whirlpool ceases, and a wave washes over you. The current grabs you like a long gentle hand and pulls you swiftly forward and down. Then, before you know what happens, the river spits you out.

The artist and the engineer are gone. You look down, and see two swans, floating down the river. They seem to nod at you.

A bicyclist rides by. You ask, “Is the library near here?”

“Yes,” says the bicyclist. “Just keep going down 6th Street until you get to Brown Avenue, then turn left. The library will be right there.”

In 1877, a group of former slaves took their new freedoms and migrated from Kentucky to Kansas, to create an African-American town. They were the first of several such westward settlements by African-Americans.

They named their town Nicodemus.

At first, the town grew quite well. A resident, Edward McCabe, was elected state auditor, becoming one of the West’s first African-Americans elected to state office. But then the town hit some roadblocks. A deal for a railroad fell through. Economic activity shifted into neighboring towns with railway stops. The Great Depression and the Dust Bowl dealt further blows to the economic vitality of Nicodemus. And yet, of all those African-American western settlements, only Nicodemus survived at all into the 21st century. According to the 2010 census, 59 people lived there.

In 1996, Nicodemus was designated a National Historic Site by the US Congress. Every July, the town holds an Emancipation Day celebration, called Homecoming, with food, music, parades, and a vintage baseball game.

You get tired. You fall asleep. The ox marches on towards your meeting.

You know what is coming. Life will be difficult. There will be failures. It’s not the promised land. It’s not Nirvana. But you have arrived. It feels like home. You stay.

Twenty-two.

My seven-year-old daughter came into my room, holding a book out in front of her, twirling around in circles as if dancing a waltz with the book as her partner, not for any particular reason, but because she is seven years old, and sometimes kids her age just bubble over with a pure joie de vivre that we adults somehow have lost along the way.

“Here, read me this,” she said. The book was Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. “Read me the parts where the kids get in trouble.” So I did. I read her the chapter where Augustus Gloop goes up the pipe, the chapter where Violet Beauregarde turns into a blueberry, and the chapter where Veruca Salt goes down the garbage chute.

Then she got distracted, and headed off to do something else. I put the book down on my bed.

A short while later, my freshman daughter came in. She was still worrying about her English test. So I said, OK, let’s practice.

She knew that her test was going to involve comparing To Kill a Mockingbird and Of Mice and Men to some unknown text she would get on test day. So I picked up the book from my bed and said, and said, OK, let’s compare Charlie and the Chocolate Factory to your two books. We figured out that justice and innocence were strong themes in all three books, and she could use those themes to build an essay around. She practiced building some thesis sentences from those ideas, and then wrote a practice essay. After all that, she felt more prepared, less worried, more confident.

As she left, it got me thinking about the difference between age seven and age fourteen. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is a book about perfect justice. In the end, the bad people get exactly the punishment they deserve, and the good people get exactly the reward they deserve. When you’re seven, you still believe the world works that way.

Somewhere in the following seven years, you figure out that it doesn’t. By high school, you’ve moved on from the childish, cartoon version of justice, to a more adult, realistic version. You’re reading things like Mockingbird and Mice where you see that justice is imperfect at best, impossible at worst.

Twenty-three.

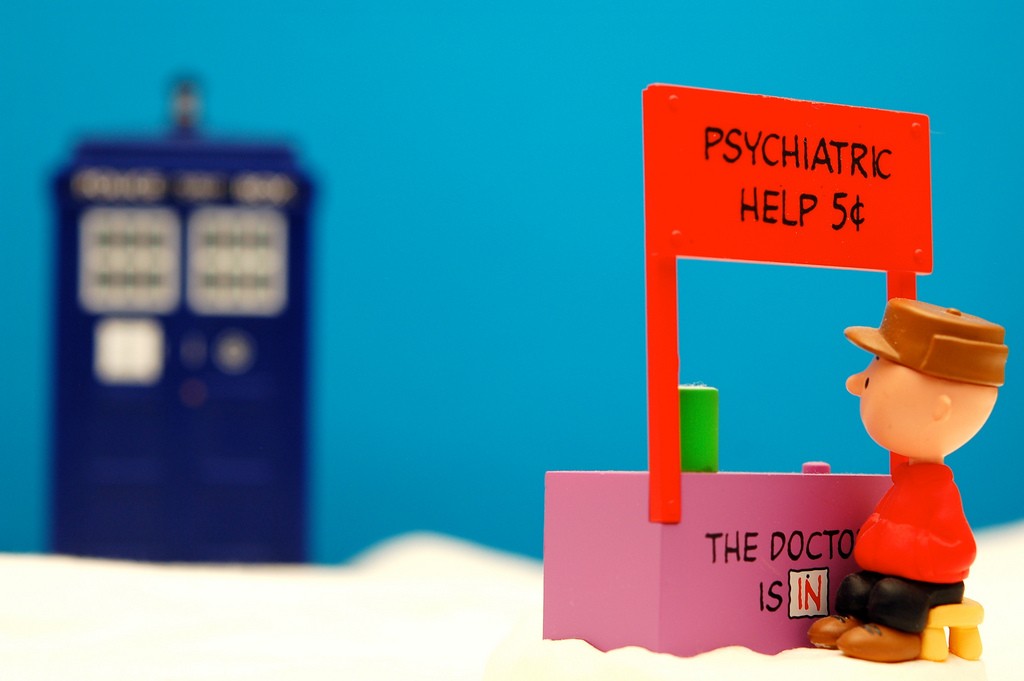

By the 1960s, when Doctor Who was created, this setting was untenable. The British empire, like other European empires, was ending. India gained independence in 1947. African territories followed in the 1950s and 1960s. Jamaican independence in 1962 began the end of the British control in the Caribbean. Within a relatively short amount of time, the exotic colonies were sovereign states. Bringing home treasure was extraditable. Racially segregated governing was apartheid. This is not to say that Britain immediately embraced absolute multicultural tolerance, but many of the geopolitical realities that underpinned imperial adventure books were gone.

In this milieu Doctor Who appeared. In many ways, the show carried on the themes of Victorian youth literature: the Doctor is a fearless traveler; he encounters strange cultures and lands; he is stoic, sophisticated, and not without a few eccentricities. Give him a pith helmet and he could fit in perfectly with the entertainment of the past.

And maybe, when your empire is falling apart, you need to believe, more strongly than ever, that justice is still possible. For Doctor Who is, in a way, just like Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, a story of perfect justice: the monsters always lose, the Doctor always wins, and Earth always survives.

Which is why I find the juxtaposition of the TARDIS with Charlie Brown in this photo especially poignant. Charlie Brown exists perpetually at the age, maybe around age 8 or so, where he is discovering that the world is unjust, that the good guys don’t always win, and that maybe they even always lose. But he has not yet reached the age where he has stopped believing in justice. He still believes that this time, he can win that baseball game, that he can fly that kite, that he can kick that football. When he visits the psychiatrist’s booth, he still expects the doctor will fix things for him. But he never gets The Doctor. He gets the fake doctor named Lucy.

As a parent, I want to be The Doctor for my seven year old. I want to keep life fair for her, to protect her from monsters, forever. But Lucy is coming. That is life. It is sad, heartbreaking even, but she must grow up. Lucy has to come.

Twenty-four.

Every technology has a prejudice. Like language itself, it predisposes us to favor and value certain perspectives and accomplishments. In a culture without writing, human memory is of the greatest importance, as are the proverbs, sayings and songs which contain the accumulated oral wisdom of centuries. That is why Solomon was thought to be the wisest of men. In Kings I we are told he knew 3,000 proverbs. But in a culture with writing, such feats of memory are considered a waste of time, and proverbs are merely irrelevant fancies. The writing person favors logical organization and systematic analysis, not proverbs. The telegraphic person values speed, not introspection. The television person values immediacy, not history.

The first time I had my mind blown by my own prejudice was at the Nigerian Embassy. My office was in the room with all the filing cabinets. Diplomats would come into my office throughout the day to retrieve and return files. But there was no system to keep track of who had what file. So the diplomats would often spend large portions of their day going from office to office to track down files that they needed.

The office manager, who was a Canadian, proposed a simple solution: have me write down when somebody takes a file from the file cabinets, and then if someone else is looking for the file, they don’t have to go door-to-door looking for it, they could just come to me and ask who has it.

The ambassador rejected that idea. Doing so would give me, a lowly translator, a form of authority over diplomats, who were ranked higher than me. That was unacceptable.

This, as I said, blew my mind. As an American, and a Swede, I would never in a million years have even conceived of the notion that a simple bureaucratic routine could rip a hole in the fabric of a culture. Of course you organize yourself in the most efficient system, I thought; or actually, I didn’t think, I just assumed that’s what everybody does, without any giving it any thought at all. Very few of us are Nicodemuses, with enough of an open mind and a courageous heart to venture outside our comfortable perspectives, to question our whole way of thinking.

I had a prejudice: I worshipped efficiency so thoroughly, and had woven it into my worldview so completely, that I didn’t even realize I was doing it. And when I was exposed to a culture that did not do so, I was utterly shocked.

That exposure was a blessing, for afterwards I could see the trade-offs we make when we choose efficiency over its alternatives. Efficiency puts us into boxes, makes us put on masks: I’m no longer Ken Arneson, but instead I’m a customer service rep for BigCorp, and I have to follow these rules in order to make a transaction. What we lose is a bit of our freedom and our humanity–a transaction by humans in an efficient system is often little more than a transaction between two technologies with human interfaces, not a transaction between free, individual humans.

There was something so much more refreshingly human and intimate about being around the Nigerians, because they all seemed to be free of those masks of efficiency we put on ourselves in the West. Of course, there’s a trade-off with that, too. When nobody is simply an extension of an efficient technology, but is always an individual free to do what he or she wants, there are no rules dictated by efficiency, there are only the rules that two free individuals agree to between themselves. And that’s where the kind of corruption you see in third-world countries happens. Such corruption is often the very thing that keeps them being third-world countries.

I wonder if, twenty-five years after my Nigerian Embassy job, they still spend much of their days chasing files around instead of using a more efficient system. I doubt it. You can’t keep the monsters of efficiency away forever. Sooner or later, Lucy comes for everybody.

Twenty-five.

What is sacred in one society is not always sacred in another. […] In the past, sacred things always derived from nature. Currently, nature has been completely desacralized and we consider technology as something sacred.

Think, for example, of the fuss whenever a demonstration is held. Everyone is then always very shocked if a car is set on fire. For then a sacred object is destroyed.

Often in the last few months, I have heard helicopters overhead, tracking protestors in Oakland, near my hometown of Alameda.

Here’s #Oakland, CA at 1:34am. #Ferguson pic.twitter.com/V7BcZ7Hpam

— Tom Brenner (@Tom_Brenner) November 25, 2014

The American justice system didn’t arise spontaneously from nature. It may not have any mechanical parts to it, but it was invented by humans. It puts boxes around human behavior and tries to make that behavior fit inside that box. When it fails us, we say that it is “broken” and needs to be “fixed.” Ultimately, it has its roots in physics and biology and human psychology. And it has its prejudices.

Twenty-six.

In 1893, Henry Ossawa Tanner attended the Chicago World’s Fair, where he almost certainly saw Nicola Tesla’s exhibit of wirelessly-powered fluorescent-tube lamps and neon lights.

Three years later, Tanner painted this picture of the Annunciation, the moment when an angel, Gabriel, comes to Mary and tells her she is going to give birth to Jesus.

This, to me, signifies the moment when modern culture crossed over from worshiping nature to worshiping technology. Up until this time, angels were nearly always depicted as a cross between mankind and nature, a human with wings. But here, the angel is basically a neon light, more technological than natural.

Tanner, of course, still manages to keep the balance between the human and the divine. The angel is pure light, but the rest of the room is imperfect. Mary has a very human expression on her face–curious, skeptical, intrigued–not the sort of blank, coldly perfect expressions of holiness you often see in religious paintings. The walls and the floors are worn. The rug on the floor has a wrinkle in it. And Mary’s toes are sticking out from under the sheet.

Oh, those toes! Those toes always tickle me. I love those toes.

Twenty-seven.

The neon lights invented by Tesla work by exciting neon gas inside a tube. Half a century later, a similar idea of exciting molecules inside a tube in a more directed fashion led to the invention of the laser.

The physicist who led the invention of the laser, Charles Townes, passed away recently. I met him a couple of times at UC Berkeley events. I found him to be a genuinely nice and charming man. You’d never know from his pleasant demeanor that he did kick-ass things like inventing laser beams (for which he won the Nobel Prize in physics in 1964), and discovering that there is a black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy.

We must also expect paradoxes, and not be surprised or unduly troubled by them. We know of paradoxes in physics, such as that concerning the nature of light, which have been resolved by deeper understanding. We know of some which are still unresolved. In the realm of religion, we are troubled by the suffering around us and its apparent inconsistency with a God of love. Such paradoxes confronting science do not usually destroy our faith in science. They simply remind us of a limited understanding, and at times provide a key to learning more.

Perhaps there will be in the realm of religion cases of the uncertainty principle, which we now know is a characteristic phenomenon of physics. If it is fundamentally impossible to determine accurately both the position and velocity of a particle, it should not surprise us if similar limitations occur in other aspects of our experience.

There are some things that are undiscovered, and other things that are undiscoverable. It is often hard to tell the difference between the two.

So we try. And sometimes we succeed, and that thing that was once undiscovered is now discovered.

Other times, all we are doing is attempting to define the undefinable, to fit something unboxable into a box, by personifying it, by giving it a name, by telling stories about it. In doing so, we are hoping that the thing we want to understand isn’t actually unknowable, but merely unknown. In this case, our attempts end up being futile.

Perhaps Townes’ religious uncertainty principle is this: the unboxable cannot be put into a box. If the divine is, as Tanner thought, “universal, elusive and unrepresentable,” then your attempts to depict it will end up being specific instead of universal, and represented instead of unrepresentable. Success will elude you. You cannot peg God for exactly what He is.

This is the paradox of organized religion. It is a box whose purpose is to contain the uncontainable. And the more tightly it organizes itself, the more strongly it holds onto the shape of that box, the less it captures the very thing it is trying to capture. The human failure to understand this paradox is why religions that are supposed to show us the way to peace and love so often end up expressing its opposite, instead. As Rumi said, “Define and narrow me, you starve yourself of yourself. / Nail me down in a box of cold words, that box is your coffin.”

Every human technology, including organized religions, has a prejudice. Perhaps the best we can do is to humbly remind ourselves of our limitations and prejudices, like the Judaism 101 website where “God” is spelled “G-d”, to represent the fact that no matter which way to try to describe G-d, you’re going to be missing something.

Twenty-eight.

Twenty-nine.

Is everything clear now?

No, I didn’t think so. We’ve sifted through a lot of data, a lot of information, a lot of ideas. We’ve found some things that unexpectedly correlate from here to there. But it still sounds complicated and convoluted.

So let us not stop here. We have 42 boxes, after all, not 29. But before we keep going on and try to bring this all together into a single coherent thesis, let us pause for a moment and try to summarize what we have learned so far.

The two biggest themes we’ve covered have been justice and religion. They are not completely independent themes; there is a lot of overlap. There are three basic approaches to each of these themes:

-

The Children’s Version.

Kids under the age of 8 or so aren’t ready to understand complex and nuanced arguments about justice or religion. So we tell them stories where the concepts are simplified and packaged into nice, tidy boxes for easy consumption. We tell kids the way things ought to be, and pretend that they actually are that way.

-

The Adult Version.

Adults know that morality and ethics don’t always fit into nice, tidy boxes. The values that we think we ought to live by often come in conflict with each other. Equality can conflict with liberty. Loving your neighbor can conflict with keeping the sabbath day holy. The right to free speech can conflict with the commandment to not make graven images.

The adult versions of justice and religion address the way things are, and present stories and rituals for living in the real world, not just in a fantasyland made for children. These versions require people to accept trade-offs and paradoxes and the limitations of human speech and knowledge. It’s not the kind of thing you can easily package into a tweet, or a 30-second commercial.

-

The Militant Version.

There are plenty of adults, lots and lots of them, who never move on from the children’s version of justice and/or religion. They insist that the nice, tidy boxes are the reality of things. And when things won’t fit into nice, tidy boxes for them, they get angry. Very, very angry. Go scroll through social media sometime, and you’ll see lots and lots of people very, very angry about things not fitting into nice, tidy boxes for them, and spewing all sorts of vile hatred at the people who they suspect keep them from their nice, tidy boxes.

Note that militant atheists fit into this version, too. I’ve seen them spew all sorts of hatred at those religionists who keep them from their nice, tidy, scientific rationalist boxes. This is a bit of a paradox, too, how a group can oppose religion while at the same time incorporating the worst aspect of it.

Thirty.

Let’s explore a couple of other themes we’ve touched on: intimacy and technology.

Last fall, Apple introduced the Apple Watch. As is usual from Apple, it looks like a lovely piece of design and engineering. Apple has its worshipers, and at times, I confess I may have been among them. Apple knows how to tempt you.

But I think this may have been the first time in forever where I saw a new Apple product and did not think, “I want one of those.” On the contrary, even if I got an Apple Watch for free, I doubt I would use it.

But the words that Tim Cook dwelled on most when talking about the Apple Watch were not the hyperbolic exclamations like “incredible” and “amazing” (though those words were certainly uttered with some frequency today). His language reflected a softer tone. The magic terms were “personal” and “intimate.”

“Apple Watch is the most personal device we’ve ever created,” said Cook.

Think about this. Apple is one of the world’s biggest, most profitable and most powerful companies. It is a corporate Leviathan. Yet it has staked its claim on intimacy, tapping the private impulses of hundreds of millions of users.

Is this a new inflection point? Where technology, having conquered the divine, now aims at a new target: the human?

What rough Henry Ossawa Tanner, its hour come round at last, slouches toward Bethlehem to paint an Apple device on Mary’s toes?

Thirty-one.

Intimacy is rare in human relationships. Few of us allow more than a handful of people into our inner circles, to share with them our strengths and our weaknesses, our deepest fears and greatest desires.

We keep our inner circles small because vulnerability is at the core of human experience. If you share these intimate details with too many people, one of them is bound to use your weaknesses to harm and/or exploit you.

This vulnerability emerges from human anatomy and psychology. We are vulnerable because we are mortal. We are vulnerable because we are frail, especially at the beginning and ends of our lifespans. We are vulnerable because we have basic needs for resources, which can be taken or kept from us. We are vulnerable because we are hierarchical; we crave the status of having those resources and fear the humiliation of lacking them. We are vulnerable because we are social; we crave belonging and fear rejection and loneliness. We are vulnerable because we are each just a single individual, amongst the collective coercive power of seven billion others. And we are vulnerable because we each desire the nice, tidy box of a stable, predictable environment, but we have very little control over how chaotic the world is.

Thirty-two.

It’s a cliché to fall in love with your kids when you first see them. But honestly, a child’s birth is a quite bizarre, alien process. If there were six-foot-tall people walking around looking like babies fresh out of the womb, it would give you nightmares. They come out all slimy and bloody and wrinkly, with this weird wormy-looking thing growing out of their stomachs, which is basically an interface for them to act as a parasite on a human host and suck energy and nutrients from them. It’s horror movie stuff, really.

But then the plot of the story twists from being a monster movie to a love story. It happens when you’re holding that new baby in your arms, and she’s looking at you, and you’re looking at her, and she looks so frail, like any little accident could just break her, and you start to feel afraid of all the things that could hurt her. And then…her eyes grow heavy, and her blinks grow longer and longer, until her eyes close for good, and she falls asleep, right there, in your arms. And you realize at that moment that even though she is completely vulnerable, she trusts you, completely.

It’s that complete trust that gets me, every time.

vulnerability + trust => love

and then we spend the rest of our lives in various states of forgetting one part of the equation or another.

Thirty-three.

“Of course machines can’t think as people do. A machine is different from a person. At least they think differently. The interesting question is, just because something thinks differently from you, does that mean it’s not thinking?

We allow for humans to have such divergencies from another. You like strawberries. I hate ice skating. You cry at sad films. I am allergic to pollen. What is the point of different tastes, different preferences, if not to say that our brains work differently, that we think differently?

And if we can say that about one another, then why can’t we say the same thing for brains built of copper and wire and steel?”

–Benedict Cumberbatch as Alan Turing, in The Imitation Game

Technological threats are also a mainstay of fiction these days. And I think the reason that technology can seem so threatening is that there is no part of the equation vulnerability + trust => love which we can be sure applies to technology. Are machines vulnerable? Can they trust? Can they be trusted with the vulnerability of others? Are they capable of love?

Idris: It’s me. I’m the TARDIS.

The Doctor: No you’re not! You’re a bitey mad lady. The TARDIS is up-and-downy stuff in a big blue box.

Idris: Yes, that’s me. A type 40 TARDIS. I was already a museum piece when you were young. And the first time you touched my console, you said—

The Doctor: I said you were the most beautiful thing I’d ever known.

Idris: Then you stole me. And I stole you.

The Doctor: I borrowed you.

Idris: Borrowing implies the eventual intention to return the thing that was taken. What makes you think I would ever give you back?

When you personify a technology, the technology acquires needs, desires, intentions. The relationship between man and machine man becomes just like any human relationship: a negotiation between vulnerability and trust.

The Doctor thinks he’s been manipulating the machine, but all this time, the machine has viewed it the other way around: she’s been manipulating him. But regardless of their point of view, they trust each other, because trust is a function of time, and the Doctor and the TARDIS have been together for centuries. They accept their relationship with each other.

And that makes sense, because Doctor Who has a perfect, cartoonish version of justice, and it would be difficult to sustain that if its hero didn’t also have a perfect, cartoonish version of his technology, where the relationship between man and machine works intimately and perfectly, in pure symbiosis.

Of course, our relationship with technology, and the corporations that make them, is not a children’s story where there are good guys and bad guys. Corporations tend to evolve to survive in a zone between symbiosis and parasitism. Competition keeps businesses from venturing too far down the parasitic path, and profit incentives keep them from pure symbiosis.

Still, when technology companies start saying they want to become intimate with their customers, we need to throw up caution flags. Intimacy adds a new level of vulnerability to the users of these technologies. We should not worship these technologies so blindly that we dismiss the vulnerabilities they present.

Since trust is the antidote for vulnerability, this technointimacy requires new levels of trust from the customers, and new levels of trustworthiness from the businesses. This trust should not be given, but earned, over time.

There’s been talk lately about “The Singularity”, the point in history, perhaps about 25 years hence, when artificial intelligence finally exceeds human intelligence. What happens then? Some very smart people are actually quite worried about it. Can we trust a technology that is smarter than us? What happens if the worst case scenario comes to pass, if this advanced technology becomes parasitic or outright hostile?

Well, then we are back to where we were at the beginning of the human race, when we were at the mercy of things we could not understand and could not control. And there’s one human institution that for millenia has been dealing with the very question of what to do in a complicated and convoluted world full of things we cannot control: religion.

Whether we are religious or atheist, we would be wise to take a deep look to the ancient, adult version of religion, to figure out how and why it has evolved to do the things it does, to guide us through the process of facing our new, technological dilemmas.

Thirty-four.

The children’s version of the history of religion is that everything, all the stories and rules and rituals, appeared on the earth in a single moment of pure and perfect enlightenment. The adult version, of course, recognizes that while there may have been some moments of inspiration along the way, most of these things have evolved over time.

As with anything that evolves over time, the reason a particular attribute exists often ends up forgotten, if it was ever consciously understood at all. The people who take over the legacy system often get so busy trying to manage these individual parts that they never learn to see how a particular part fits into the whole picture.

When you manage a complex technological system, whether it’s a religious order or a computer network, you learn that these complex systems rarely function smoothly. There’s always one part of the system that is slower, or less efficient, than the rest of the system. This slowest part of the system will inevitably draw your attention. If anything goes wrong, it’s the part your users complain about. Since every other part of the system is faster or better, this slowest part holds back everything else in the chain. It’s a bottleneck.

There’s always some sort of bottleneck, somewhere. The question is whether the bottleneck is a problem or not.

When you have a bottleneck that’s a problem, and then you fix it, it feels great. For a while. But then you notice, oh no, look now that other thing over there. That other thing is now the slowest part of the system. You have a new bottleneck, which you had never even noticed was a problem before.

You keep doing this, over and over and over. What you end up with is a complicated system full of convoluted solutions, that somehow gets the job done, even if it’s so complicated and convoluted that you don’t really understand anymore why it works.

Thirty-five.

The American justice system is another example of a complex technological system. It has its bottlenecks. There are some parts of it that noticably do not function as well as other parts. These bottlenecks have been especially painful for African-Americans, as the recent protests have demonstrated.

First there was slavery, and when that was fixed, segregation became the bottleneck, and when that was fixed, it became voting rights, and when that was fixed it became housing discrimination, and when that was fixed, it became police brutality.

And when police brutality is fixed, there will probably be some other bottleneck in the system that becomes noticeable. Perhaps it will be a new problem not on our radar yet. Or perhaps one of the old ones, like voting rights or housing, will return, because “fixing” a problem in a technological system doesn’t always mean the problem goes away completely. Sometimes it just means fixing it to the point where it’s not the worst part of the system anymore.

But it’s frustrating to have to keep fixing bottlenecks. The more often you have to do so, the less you trust not only the system, but the process of fixing the system. You’d think it would be possible to do better.

Thirty-six.

One of the principles that was drilled into me as a young computer programmer was a distrust of random numbers of things. “You should only program for zero, one, or infinity cases,” an older engineer once told me. “If you’re programming for exactly two or three or forty-two cases, you don’t understand the problem well enough. You’re making exceptions, and the exceptions will never stop.”

In other words, if you don’t want to spend the rest of your life chasing down bottlenecks, make a better technology. And to do that, you need to dig down deeper to understand the problem and the tools you have to address those problems. For it is only when you get to the heart of the problem that the whole range of possible solutions opens up to you. Until then, you are boxed in by the problems themselves.

So when I see a list of things like “10 Things I Believe” or “Forty-two Boxes”, I automatically distrust them. Why did we draw a wall around these things in this particular way? Why did I include 10 things, but left out infinity-minus-10 others? Why does this convoluted essay have forty-two boxes and not ninety-five? Or a million?

Can this list keep going to infinity? Or can this list be reduced to a single, underlying principle?

Thirty-seven.

This sentence from the Declaration of Independence is a list of the rights we Americans value. Specifically, it lists four of them: equality, life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

The engineer in me has been bothered by this list for many years. Why four values? Why not ten, or twenty-seven, or forty-two? Can the list go to infinity? Is there one, underlying principle behind these values?

And then one day, not too long ago, I read this sentence again. On about my ten thousandth reading of it, I finally actually read it. The one underlying principle has been right there, all this time, in the sentence. I had over the years so firmly boxed in my understanding of that sentence that I just didn’t see it, right there in front of my eyes. A principle so important that the Founding Fathers saw fit to repeat the principle twice in that one sentence.

Created. Creator.

So remember when I said in that baseball essay that all higher sabermetric truths are derived from lower-level truths about physics, biology, and psychology? And how that essay struck a nerve?

This is the same idea. The. Exact. Same. Idea.

(Smh at me thinking I have an original idea when it turns out to be centuries old…there is nothing new under the sun.)

It doesn’t matter if you believe if we were created by God, or by evolution. Either way, the need for the rights to equality and life and liberty and happiness pursuit derive from the output of that creation, human nature.

These rights didn’t strike a nerve and spread like wildfire across the planet simply because they are independently valuable moral concepts. They spread around the world because they did a better job at taking the core human condition, vulnerability, and applying its antidote, trust.

If you can trust that the law applies to everyone equally, then justice is no longer arbitrary, and you are less vulnerable, and more in control of your life. If you can trust that you are free to act however you see fit without punishment, then you are less vulnerable to taking risks. When you reduce people’s downside of taking risks, you open up all sorts of new upsides that were never available before.

The result of this lowered vulnerability and increased trust is that Americans have become the most productive humans in the history of earth.

But trust is the key. You can’t take American values like free speech or democracy and just plop them down in a place like Iraq or Afghanistan and expect them to work. These aren’t first-order concepts, they’re third- or fourth-order concepts. The first order is vulnerability. The second order is trust. You need to create an environment where people trust these concepts. Without trust, they don’t work. With trust, the rest follows.

Thirty-eight.

My daughter said that they didn’t laugh because they thought my idea was ridiculous. They laughed because it was such a Ken Arneson Thing To Say.

She said I always approach problems like an engineer. Add the right technology here or there, Ken Arneson believes, and that bottleneck can disappear. Even when that bottleneck involves imperfect, unpredictable human personalities.

She got me there. Pegged me for exactly what I am. The engineer’s mentality is the box I live in. I have my prejudices.

I wanted my house to fit into nice, tidy boxes. And I was trying to put those same boxes around my kids. When I realized, when they laughed at me, that my world didn’t work like that, I got angry. Very, very angry.

That anger was a sign that I was worshiping the wrong thing. I was placing my faith in technology ahead of people.

I needed to let go of the mindset that I can control everything with technology. I needed be like Nicodemus, to let go of my comfortable position as the wise elder, to humble myself, to go seek out the first principles. I needed to go figure out why I feel vulnerable in a messy house, and explain it to my kids. I needed to trust them to understand my point of view, and me likewise theirs, and then to trust ourselves to follow up and do the right thing.

It’s a funny thing, parenting. You think you’re going to be the teacher, but so often you end up being the student, instead.

Thirty-nine.

If there is something that the adult forms of all the major religions share in common, it is that they all want to guide people towards first principles. The concept is pretty much the same, but the stories they tell to get there differ in details.

The monotheistic religions call this first principle God. Hinduism calls it Brahman. The adult versions of these religions tell the story that God, or Brahman, is beyond the ability of humans to define it. Which isn’t very helpful, if you think about it, because if we can’t understand the first principle, what good does it do to be guided there?

The answer is that surrendering to not understanding leads you directly to Principle 1A: that no matter what you do, there will be things that are beyond your control, which makes you vulnerable, which leads to suffering.

Buddhism doesn’t try to personify this principle, and therefore often calls itself a philosophy instead of a religion, but it too has a First Noble Truth, which it calls Dukkha. Basically, it says that “life is suffering.”

Heck, even the first step in the 12-step addiction protocols is to get yourself to admit your lack of control, and say, “I am powerless over my addiction.” These same themes keep showing up, again and again. Because human nature is essentially the same, in every place, and every time.

This seems very simple, but it can become difficult to grasp from here. Partly because several paradoxes emerge from this first principle.

One paradox is that you are dependent on others to create the trusting environment you need to fulfill your potential as an individual. You need to trust them, and they need to trust you. In science, we say that people evolved the “theory of mind“, the ability to think and feel what other people are thinking and feeling. The ability to mentally step into someone else’s shoes is the origin of morality. The story of the original sin, of eating from the Tree of Knowledge in the Book of Genesis is basically a story about the theory of mind. The Golden Rule also derives from this.

Another paradox is expressed in Buddhism’s second principle: the desire to find ways to take control of our vulnerability and suffering actually leads to more vulnerability and suffering. Because you can’t get rid of your vulnerability, and you end up attaching yourself to your efforts to rid yourself of it, instead of attaching yourself to the first principle. Buddhism emphasizes methods to rid yourself of these desires.

The other religions say similar things. Islam emphasizes, “There is no God but God.” The fourth, seventh, or thirty-ninth principle is not the first principle, so don’t get attached to it. That’s why they don’t want you to draw pictures of Mohammad. Not because you should respect Mohammad as the first principle, but because Mohammad is not the first principle. Don’t worship the wrong thing.

There’s a Zen Buddhist saying: the obstacle is the path. It’s counterintuitive that the proper technique for dealing with vulnerability is not avoidance. The path is through the obstacle, through the vulnerability, through the pain, through the suffering. Face it, head on.

The only way to succeed in doing that is if you have trust. You need trust in whatever it takes to get you through the obstacle: trust in God, trust in the process, trust in the people around you. If you don’t have trust, you’ll turn around, and return to the shelter of those confining boxes. You’ll never be free.

It should be a comfort that all these traditions all seem to tell the same stories, over and over again.

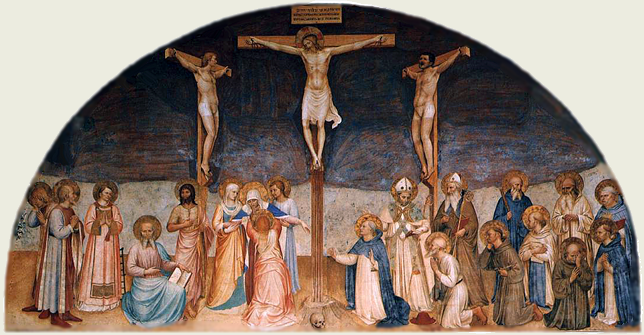

The religious tradition I grew up in, Christianity, tells all these stories, as well. It is the most popular religion on earth. Why did this religion strike a nerve, above all the other similar religions? I think it’s in that image of Christ, up there on the cross, being tortured to death. It takes the core condition of human nature, our vulnerability, and puts it front and center.

The Crucifixion tells us that even if you put God Himself in human form, He would suffer and die. Do not fear this vulnerability. Seek it out. Go through it. Then, and only then, will all the possibilities you have in this world open up to you.

Forty.

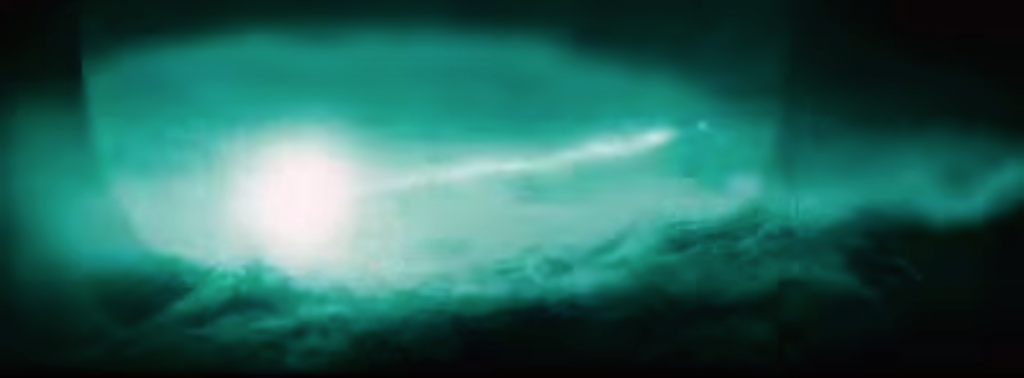

This image is from a climactic scene in the Harry Potter series of films. It looks like something Henry Ossawa Tanner could have painted.

J.K. Rowling has done a remarkable job with the Harry Potter stories. All of the themes we’ve been talking about can be found in those seven books, too. It starts as a children’s story, but evolves into something much more than that. In the end, Harry becomes an adult, and the story treats him like one. The justice in the end isn’t nice and tidy. There is plenty of death and suffering. But there is also justice, because Harry approaches his obstacles in the proper way.

The primary conflict in the stories are between Harry and Voldemort. They are joined together, and vulnerable to each other, in ways neither of them really understands. The difference between the two is that Voldemort does not accept his vulnerability, so he tries to control it, and even defeat it, with complicated magical technology. Ultimately, Voldemort trusts no one. No one trusts him, either, or loves him. He gets things accomplished only through fear, not through trust and love.

Harry, on the other hand, is a very Buddha-like character. He does not desire wealth or power, although these things come to him. He trusts others, and inspires trust and love and loyalty in return. In the end, he triumphs precisely because he does not desire anything, and because he accepts his own vulnerability.

“I was scared that, if presented outright with the facts about these tempting objects, you might seize the Hallows as I did, at the wrong time, for the wrong reasons. If you laid hands on them, I wanted you to possess them safely. You are the true master of death, because the true master does not seek to run away from Death. He accepts that he must die, and understands that there are far, far worse things in the living world than dying.”

–Dumbledore, in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows

Forty-one.