As I was writing a letter to my third-grade daughter’s principal in support of a change in homework policy (a letter which I’ve posted here), it occurred to me I was making a point about a phenomenon that isn’t unique to education at all, but happens in a lot of other fields, too: baseball, business, economics, and politics.

I don’t know if this phenomenon has a name. It probably does, because you’re very rarely the first person to think of an idea. If it does, I’m sure someone will soon enlighten me. The phenomenon goes like this:

* * *

Suppose you suck at something. Doesn’t matter what it is. You’re bad at this thing, and you know it. You don’t really understand why you’re so bad, but you know you could be so much better. One day, you get tired of sucking, and you decide it’s time to commit yourself to a program of systematic improvement, to try to be good at the thing you want to be good at.

So you decide to collect data on what you are doing, and then study that data to learn where exactly things are going so wrong. Then you’ll try some experiments to see what effect those experiments have on your results. Then you keep the good stuff, and throw out the bad stuff, and pretty soon you find yourself getting better and better at this thing you used to suck at.

So far so good, eh? But there’s a problem. You don’t really notice there’s a problem, because things are getting better and better. But the problem is there, and it has been there the whole time. The problem is this: the thing your data is measuring is not *exactly* the thing you’re trying to accomplish.

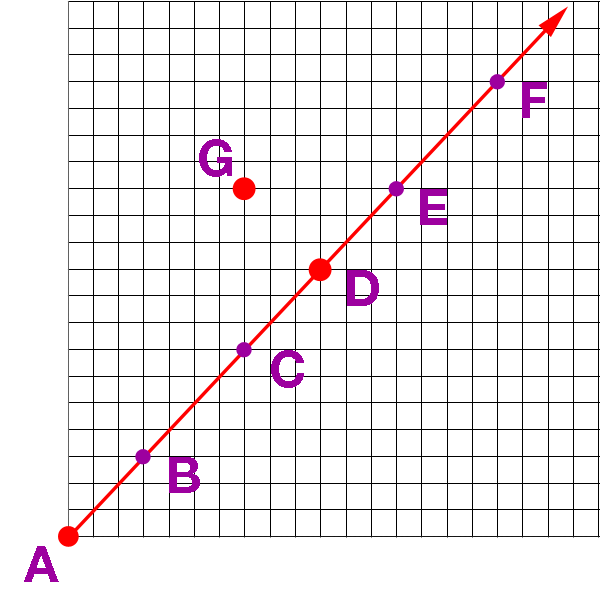

Why is this a problem? Let’s make a simplified graph of this issue, so I can explain.

Let’s call the place you started at, the point where you really sucked, “Point A”.

Let’s call the goal you’re trying to reach “Point G”.

And let’s call the best place the data can lead you to “Point D”.

Note that Point D is near Point G, but it’s not exactly the same point. Doesn’t matter why they’re not the same point. Perhaps some part of your goal is not a thing that can be measured easily with data. Maybe you have more than one goal at a time, or your goals change over time. Whatever, doesn’t matter why, it just matters they’re just not exactly the same point.

Now here’s what happens:

You start out very far from your goal. You likely don’t even know exactly what or where your goal is, precisely, but (a) you’ll know it when you see it, and (b) know it’s sorta in the Point D direction. So, off you go. You embark on your data-driven journey. As a simplified example, we’ll graph your journey like this:

On this particular graph, your starting point, Point A, is 14.8 units away from your goal at Point G. Then you start following the path that the data leads you. You gather data, test, experiment, study the results, and repeat.

After a period of time, you reach Point B on the graph. You are now 10.8 units away from your goal. Wow, you think, this data-driven system is great! Look how much better you are than you were before!

So you keep going. You eventually reach Point C. You’re even closer now: only 6.0 units away from your goal!

And so you invest even more into your data-driven approach, because you’ve had nothing but success with it so far. You organize everything you do around this process. The process, and changes that you’ve made because of it, actually begin to become your new identity.

In time, you reach Point D. Amazing! You’re only 4.2 units away from your goal now! Everything is awesome! You believe in this process wholeheartedly now. The lessons you’ve learned permeate your entire worldview now. To deviate from the process would be insane, a betrayal of your values, a rejection of the very ideas you stand for. You can’t even imagine that the path you’ve chosen will not get any better than right here, now, at Point D.

Full speed ahead!

And then you reach Point E.

Eek!

Egads, you’re 6.00 units away from your goal now. You’ve followed the data like you always have, and suddenly, for no apparent reason, things have suddenly gotten worse.

And you go, what on Earth is going on? Why are you having problems now? You never had problems before.

And you’re human, and you’ve locked into this process and weaved it into your identity. You loved Points C & D so much that you can’t stand to see them discredited, so your Cognitive Dissonance kicks in, and you start looking for Excuses. You go looking for someone or something External to blame, so you can mentally wave off this little blip in the road. It’s not you, it’s them, those Evil people over there!

But it’s not a blip in the road. It’s the road itself. The road you chose doesn’t take you all the way to your destination. It gets close, but then it zooms on by.

But you won’t accept this, not now, not after the small sample size of just one little blip. So you continue on your same trajectory, until you reach Point F.

You stop, and look around, and realize you’re now 10.8 units away from your goal. What the F? Things are still getting worse, not better! You’re having more and more problems. You’re really, really F’ed up. What do you do now?

Can you let go of your Cognitive Dissonance, of your Excuse seeking, and step off the trajectory you’ve been on for so long?

F is a really F’ing dangerous point. Because you’re really F’ing confused now. Your belief system, your identity, is being called into question. You need to change direction, but how? How do you know where to aim next if you can’t trust your data to lead you in the right direction? You could head off in a completely wrong direction, and F things up even worse than they were before. And when that happens, it becomes easy for you to say, F this, and blow the whole process up. And then you’re right back to Point A Again. All your effort and all the lessons you learned will be for nothing.

WTF do you do now?

F’ing hell!

* * *

That’s the generic version of this phenomenon. Now let’s talk about some real-world examples. Of course, in the real world, things aren’t as simple as I projected above. The real world isn’t two-dimensional, and the data doesn’t lead you in a straight line. But the phenomenon does, I believe, exist in the wild. And it’s becoming more and more common as computers make data-driven processes easy for organizations and industries to implement and follow.

Education

As I said, homework policy is what got me thinking about this phenomenon. I have no doubt whatsoever that the schools my kids are going to now are better than the ones I went to 30-40 years ago. The kids learn more information at a faster rate than my generation ever did. And that improvement, I am confident, is in many ways a result of the data-driven processes that have arisen in the education system over the last few decades. Test scores are how school districts are judged by home buyers, they’re how administrators are judged by school boards, they’re how principals are judged by administrators, and they’re how teachers are judged by principals. The numbers allow education workers to be held accountable for their performance, and provide information about what is working and what needs fixing so that schools have a process that leads to continual improvement.

From my perspective, it’s fairly obvious that my kids’ generation is smarter than mine. But: I’m also pretty sure they’re more stressed out than we were. Way more stressed out, especially when they get to high school. I feel like by the time our kids get to high school, they have internalized a pressure-to-perform ethic that has built up over years. They hear stories about how you need such and such on your SATs and this many AP classes with these particular exam scores to get into the college of their dreams. And the pressure builds as some (otherwise excellent) teachers think nothing of giving hours and hours of homework every day.

Depression, anxiety, panic attacks, psychological breakdowns that require hospitalization: I’m sure those things existed when I went to school, too, but I never heard about it, and now they seem routine. When clusters of kids who should have everything going for them end up committing suicide, something has gone wrong. That’s your Point F moment: perhaps we’ve gone too far down this data-driven path.

Whatever we decide our goal of education is, I’m pretty sure that our Point G will not feature stressed-out kids who spend every waking hour studying. That’s not the exact spot we’re trying to get to. I’m not suggesting we throw out testing or stop giving homework. I am arguing that there exists a Point D, a sweet spot with just the right amount of testing, and just the right amount of homework, that challenges kids the right amount without stressing them out, and leaves the kids with the time they deserve to just be kids. Whatever gap between Point D and Point G that remains should be closed not with data, but with wisdom.

Baseball

The first and most popular story of an industry that transforms itself with data-driven processes is probably Michael Lewis’s Moneyball. It’s the story of how the revenue-challenged Oakland A’s baseball team used statistical analysis to compete with economic powerhouses like the New York Yankees.

I’ve been an A’s fan my whole life, and I covered them closely as an A’s blogger for several years. So I can appreciate the value that the A’s emphasis on statistical analysis has produced. But as an A’s fan, there’s also a certain frustration that comes with the A’s assumption that there is no difference between Point D and Point G. The A’s assume that the best way to win is to be excruciatingly logical in their decisions, and that if you win, everyone will be happy.

But many A’s fans, including myself, do not agree with that assumption. The Point F moment for us came when, during a stretch of three straight post-season appearances, the A’s traded their two most popular players, Yoenis Cespedes and Josh Donaldson, within a span of six months.

I wrote about my displeasure with these moves in an long essay called The Long, Long History of Why I Do Not Like the Josh Donaldson Trade. My argument was, in effect, that the purpose of baseball was not merely winning, it was the emotional connection that fans feel to a team in the process of trying to win.

When you have a data-driven process that takes emotion out of your decisions, but your Point G includes emotions in the goal of the process, it’s unavoidable that you will have a gap between your Point D and your Point G. The anger and betrayal that A’s fans like myself felt about these trades is the result of the process inevitably shooting beyond its Point D.

Business

If Moneyball is not the most influential business book of the last few decades, it’s only because of Clayton Christensen’s book, The Innovator’s Dilemma. The Innovator’s Dilemma tells the story of a process in which large, established businesses can often find themselves defeated by small, upstart businesses with “disruptive innovations.”

I suppose you can think of the phenomenon described in the Innovator’s Dilemma as a subset of, or perhaps a corollary to, the phenomenon I am trying to describe. The dilemma happens because the established company has some statistical method for measuring its success, usually profit ratios or return on investment or some such thing. It’s on a data-driven track that has served it well and delivered it the success it has. Then the upstart company comes along and sells a worse product with worse statistical results, and because of these bad numbers, the establish company ignores it. But the upstart company is on an statistical path of its own, and eventually improves to the point where it passes the established company by. The established company does not realize its Point D and Point G are separate points, and finds itself turning towards Point G too late.

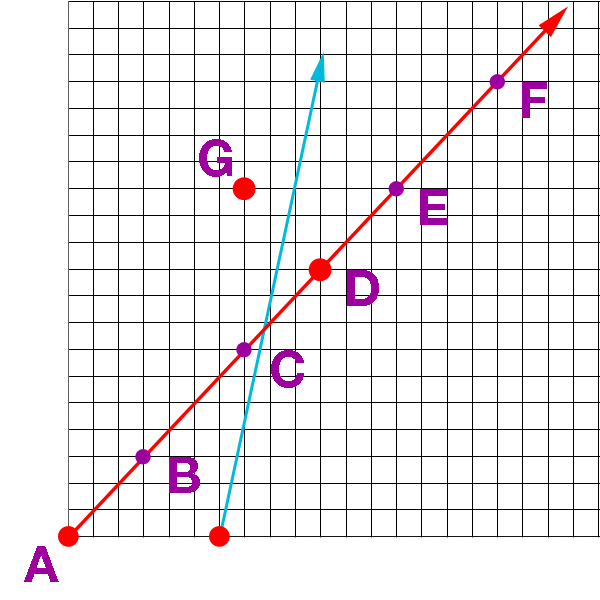

Here, let’s graph the Innovator’s Dilemma on the same scale as our phenomenon above:

The established company is the red line. They have reached Point D by the time the upstart, with the blue line, gets started. The established company thinks, they’re not a threat to us down at Point A. And even if they reach our current level at Point D, we will beyond Point F by then. They will never catch up.

This line of thinking is how Blockbuster lost to Netflix, how GM lost to Toyota, and how the newspaper industry lost its cash cow, classified ads, to Craigslist.

The mistake the establish company makes is assuming that Point G lies on/near the same path that they are currently on, that their current method of measuring success is the best path to victory in the competitive market. But it turns out that the smaller company is taking a shorter path with a more direct line to the real-life Point G, because their technology or business model has, by some twist, a different trajectory which takes it closer to Point G than the established one. By the time the larger company realizes its mistake, the smaller company has already gotten closer to Point G than the larger company, and the race is essentially over.

* * *

There are other ways in which businesses succumb to this phenomenon besides just the Innovator’s Dilemma. Those companies that hold closely to Milton Friedman’s idea that the sole purpose of a company is to maximize shareholder value are essentially saying that Point D is always the same as Point G.

But that creates political conflict with those who think that all stakeholders in a corporation (customers, employees, shareholders and the society and environment at large) need to have a role in the goals of a corporation. In that view, Point D is not the same as Point G. Maximizing profits for the shareholders will take you on a different trajectory from maximizing the outcomes for other stakeholders in various proportions. When a company forgets that, or ignores it, and shoots beyond its Point D, then there is going to inevitably be trouble. It creates distrust in the corporation in particular, and corporations in general. Take any corporate PR disaster you want as an example.

Economics

I’m a big fan of Star Trek, but one of the things I never understood about it was how they say that they don’t use money in the 23rd century. How do they measure the value of things if not by money? Our whole economic system is based on the idea that we measure economic success with money.

But if you think about it, accumulating money is not the goal of human activity. Money takes us to Point D, it’s not the path to Point G. What Star Trek is saying is that they somehow found a path to Point G without needing to pass through Point D first.

But that’s 200 years into a fictional future. Right now, in real life, we use money to measure human activity with. But money is not the goal. The goal is human welfare, human happiness, human flourishing, or some such thing. Economics can show us how to get close to the goal, but it can’t take us all the way there. There is a gap between the Point D we can reach with a money-based system of measurement, and our real-life Point G.

And as such, it will be inevitable that if we optimize our economic systems to optimize some monetary outcome, like GDP or inflation or tax revenues or some such thing, that eventually that optimization will shoot past the real-life target. In a sense, that’s kind of what we’re experiencing in our current economy. America’s GDP is fine, production is up, the inflation rate is low, unemployment is down, but there’s still a general unease about our economy. Some people point to economic inequality as the problem now, but measurements of economic inequality aren’t Point G, either, and if you optimized for that, you’d shoot past the real-life Point G, too, only in a different direction. Look at any historically Communist country (or Venezuela right now) to see how miserable missing in that direction can be.

The correct answer, as it seems to me in all of these examples, is to trust your data up to a certain point, your Point D, and then let wisdom be your guide the rest of the way.

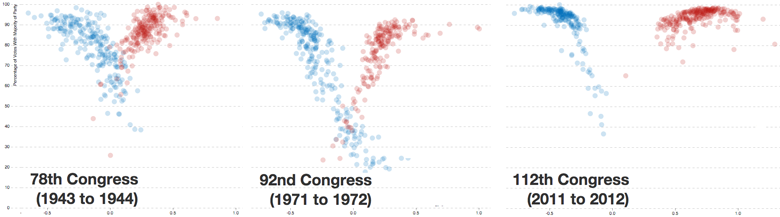

Politics

Which brings us to politics. In 2016. Hoo boy.

Well, how did we get here?

I think there are essentially two data-driven processes that have landed us where we are today. Both of these processes have a gap between what we think of as the real-life goals of these entities, and the direction that the data leads them to. One is the process of news outlets chasing media ratings. And the other is political polling.

In the case of the media, the drive for ratings pushes journalism towards sensationalism and outrage and controversy and anger and conflict and drama. What we think journalism should actually do is inform and guide us towards wisdom. Everybody says they hate the media now, because everybody knows that the gap between Point D and Point G is growing larger and larger the further down the path of ratings the media goes. But it is difficult, particularly in a time where the technology and business models that the media operate under are changing rapidly, to change direction off that track.

And then there’s political polling. The process of winning elections has grown more and more data-driven over recent decades. A candidate has to say A, B, and C, but can’t say X, Y, or Z, in order to win. They have to casts votes for D, E, and F, but can’t vote for U, V or W. They have to make this many phone calls and attend that many fundraisers and kiss the butts of such and such donors in order to raise however many millions of dollars it takes to win. The process has created a generation of robopoliticians, none of whom have an original idea in their heads at all (or if they do, won’t say so for fear of What The Numbers Say.) You pretty much know what every politician will say on every issue if you know whether there’s a “D” or an “R” next to their name. Politicans on neither side of the aisle can formulate a coherent idea of what Point G looks like other beyond a checklist spit out of a statistical regression.

That leads us to the state of the union in 2016, where both politicians and the media have overshot their respective Point Ds.

And nobody feels like anyone gives a crap about the Point G of this whole process: to make the lives of the citizens that the media and the politicians represent as fruitful as possible. Both of these groups are zooming full speed ahead towards Point F instead of Point G.

And here are the American people, standing at Point E, going, whoa whoa whoa, where are you all going? And then the Republicans put up 13 robocandidates who want to lead everybody to the Republican version of Point F, plus Donald Trump. The Democrats put up Hillary Clinton, who can probably check all the data-driven boxes more skillfully than anybody else in the world, asking to lead everybody to the Democratic version of Point F, plus Bernie Sanders.

And Trump and Sanders surprise the experts, because they’re the only ones who are saying, let’s get off this path. Trump says, this is stupid, let’s head towards Point Fascism. Sanders says, we need a revolution, let’s head towards Point Socialism.

And most Americans like me just shake our heads, unhappy with our options, because Fascism and Socialism sound more like Point A than Point G to us. I don’t want to keep going, I don’t want to start over, and I don’t want to head in some old discredited direction that other countries have headed towards and failed. I just want to turn in the direction of wisdom.

“It’s not that hard. Tell him, Wash.“

“It’s incredibly hard.”