I went to the Oakland A’s game last night, hoping to see them clinch their first playoff spot since 2006. Rather than write up my experiences, I decided to throw together a bunch of 5-second video clips I took together, to try to give you a feel of what it was like to be there last night. Here you go:

The thing I love about reading Clayton Christensen is that he provides new ways of looking at common problems, which open up a whole different set of solutions for you.

For instance, watch this video as he explains his concept of “Jobs to be Done”:

“If you understand the job, how to improve the product becomes just obvious.”

I love that phrase: “hiring a milkshake”. When you think of a milkshake as a product, then you analyze it the way you analyze products: it’s properties (thickness, taste, size, price, etc.), and the demographics of the purchasers of that product (rich, poor, male, female, young, old, etc.)

But if you look at it in terms of a “job to be done”, that one product may actually turn out to be two or more separate products. There’s the milkshake job for the morning commuter, and there’s also the milkshake job for the parent buying it for their kid. These separate products may have separate sets of properties and demographics.

* * *

Last month, I wrote about the MVP Award, in a post called Awards are Celebrations, Not Measurements. And Vice Versa. I think I had a good point there, but perhaps applying Christensen’s “Jobs to be Done” frame would make that argument clearer. So let’s do that:

What is the job that we hire the Most Valuable Player Award to do?

I suspect that the reason there seems to be such vehement disagreement about the AL MVP this year is that it’s actually like the milkshake: we think of it as one single product, but in fact it’s actually two. The morning commuters need the MVP to function like a measurement: that’s what they want to hire the job to do. The evening parents want to hire the MVP award to tell the best story, to celebrate the player who best matches our platonic or cultural ideal of what the best player should accomplish.

Sometimes a single item on the menu can successfully accomplish two jobs. But sometimes they can’t. If we’re smart at marketing, we’ll figure out how to get each set of customers the product that they actually want.

This week I’ve been reading my favorite childhood book, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, to my 5-year-old daughter. It’s a bit of an odd book in a way, because the real climax of the book comes in the middle, when the Golden Tickets are found. It has a happy ending, too, but it doesn’t quite bring that sense of elation that you get when poor Charlie Bucket finally has his first stroke of good luck. That wide-eyed giggling happiness that you share with your kid when reading a chapter like ‘The Miracle’ together — it’s absolutely one of the best things in life, ever.

* * *

I thought about taking her and my wife to the A’s game on Saturday, but Friday night I tweaked my back a bit playing soccer, so I decided it would be wisest to stay home and rest my back. I missed attending probably one of the top 10 most exciting games in Oakland history. The A’s fell behind 4-0, and were trailing 4-2 in the ninth inning. Their lead in the race for a playoff spot was about to shrink down to one game. Here is what happened next:

Josh Donaldson’s 2-run home run tied the game 4-4 in the ninth inning, and then in the extra 10th frame, Brandon Moss homered to give the A’s the win.

I love A’s radio announcer Ken Korach’s call. “The A’s — they haven’t run out of miracles yet!”

* * *

The rest of the story this season may turn out to be pretty good. Or not–the A’s may not even be Charlie Bucket in this story. Maybe their young enthusiasm leads them to make a quick, sudden exit like Violet Beauregarde, instead. Who knows. But this miracle today, the giggling, bubbly happiness I feel inside — this is undoubtedly the best part of the book.

Yesterday, I mentioned in passing how I enjoy baseball on two levels: one level in rooting for my team, and another in the aesthetic quality of the game. The day before, I defended the idea of cross-pollinating new scientific ideas with older fields of human endeavor, to see what comes out of the mix. So today, let’s make a new hybrid.

How can we explain the psychological attraction in rooting for a team? Why, when we’re watching two teams that we have no previous attachment to, do we often find ourselves rooting for one team or another anyway? And how is this different or separate from the aesthetic joy of watching a game?

* * *

As I write this, I am watching Ian Kinsler bat against my favorite baseball team, the Oakland A’s. On the rooting level, I want him to fail and flail badly. But on an aesthetic level, I admire Kinsler. His at-bats, the way he takes bad pitches and fouls off good pitches until he can get a good pitch to hit, are probably the most consistently good at-bats I’ve seen from any player since Rickey Henderson. If our enjoyment of sports were only about rooting interest, I should be incapable of appreciating Kinsler at all. If our enjoyment of sports were only aesthetic, I wouldn’t have a reason to want to see him fail.

Can baseball fandom be fully expressed in a mere two-dimensional chart, with rooting on the x-axis, and aesthetics on the y-axis? No, of course not. For instance, suppose the A’s pitcher were Bartolo Colon. Colon was suspended in August for performance enhancing drugs, but let’s say he’s served his suspension and now he’s pitching. Do I still root for him to succeed? Yes, he’s on my favorite team. But now there’s a moral dimension on the z-axis added to the mix, too. We can go on. Fandom is complex.

* * *

But still, we want to talk about it, so we need to model it. Do we need modern science to do so? Not really. For example, Aristotle, addressed such issues over two millenia ago. Here’s a paragraph on Aristotle’s aesthetics, from a 1902 version of Encyclopedia Britannica:

Elsewhere he (Aristotle) distinctly teaches that the Good and the Beautiful are different (heteron), although the Good, under certain conditions, can be called beautiful. He thus looked on the two spheres as co-ordinate species, having a certain area in common. It should be noticed that the habit of the Greek mind, in estimating the value of moral nobleness and elevation of character by their power of gratifying and impressing a spectator, gave rise to a certain ambiguity in the meaning of to kalon, which accounts for the prominence the Greek thinkers gave to the connection between the Beautiful and the Good or morally Worthy.

Not sure if Aristotle meant Good and Morally Worthy were separate things or the same, but I’ll assume they’re separate. So applying Aristotle to my example above, the A’s are Good, Ian Kinsler is Beautiful, but Bartolo Colon is Morally Unworthy.

* * *

Aristotle’s three dimensions are a kind of model of this aspect of human nature. And since this model is still being discussed 2,000 years later, we can certainly say that this model has a certain level of usefulness. But does this model accurately map to the actual structure and organization of the human brain? Can we explain this structure in terms of evolution, that there were some sort of selective pressures which led to this behavior?

Aesthetics and morality are huge subjects, so I’ll pass on those in this blog entry, and just focus on the rooting aspect.

Group behavior has always been a bit of a tricky subject for evolutionist to explain. It’s easy to explain selfish individual behavior: it’s behavior that’s directed towards passing your genes on to the next generation over the genes of your rivals. The prevailing explanation for most of the last 40 years or so has been kin selection: unselfish behavior towards your kin helps pass more of your genes along to the next generation. Any sort of unselfish behavior toward people who are not your kin is just sort of a side effect of unselfish behavior towards your kin.

But that’s an unsatisfying explanation, particularly if you apply it to team sports. Why do I go to the Coliseum, dress up in green and gold with thousands of other A’s fans, 99.999% of who are not my kin, and cheer the team together with them? It’s really hard to make a convincing argument that I’m doing it to pass my genes on.

The alternative explanation is group selection. Group selection is a theory that fell out of favor in the 1960s, but in recent years has been making a comeback. In his recent book, The Social Conquest of Earth, E.O. Wilson argues strongly in favor of group selection as an explanation for human social behavior.

Under group selection theory, human evolution happens in two dimensions. There’s a selfish dimension that pushes individuals to promote their genes over others within their group. But there’s also a dimension that pushes us to behave in ways to promote the genes of the group over the genes of rival groups. In times of war or drought or famine, those groups who behave in ways that encourage cooperation instead of selfishness survive to pass their genes on more than the groups whose individuals behave more selfishly.

Under group selection theory, the behavior we see in team sports makes much more sense. We naturally form emotional attachments to our groups, because we were evolved to do just that. As E.O. Wilson points out, every single animal that exhibits social behavior (including the one Wilson is expert in, ants) evolved its social behavior to protect and defend a nest. So we root, root, root for the home team, and find it extremely irritating when invading Yankee fans come into our home nest and chant for their team, instead. The joy we feel when our group wins, the pain we feel when our group loses — those are emotions that evolved in our brains to promote the genetic survival of our groups.

* * *

Note I said “our groups.” Jason Wojciechowski has an article today (Baseball Prospectus, $ required) on the use of the word ‘we’ in reference to team sports. Is it appropriate for fans to use the word “we”, or should that be limited only to the players on the team? Jason tries to define that line somewhere in along the lower level employees of the team. I don’t think that works (which Jason ultimately acknowledges).

Former Baseball Prospectus writer Kevin Goldstein used to rail against fans using ‘we’ on Twitter all the time. At one point (which I can’t find now — Twitter search sucks) — he argued that you don’t say ‘we’ to refer to your favorite band, so why should you do so for your favorite team?

I strongly disagree with Kevin here. A band is different from a team. You like the band primarily because of the aesthetic experience it provides you. But as we’ve seen here, the aesthetic experience is only a small part of the experience of watching baseball. Sports are the most popular activity on earth right now not because they provides an aesthetic experience alone — but because they have gone beyond that and tapped into the a primal root of human evolution: the network of emotions that group selection has hardwired into us.

The reason professional sports is a profession at all is because it creates the feeling of ‘we’. That feeling is the main point of team sports. We-ness is the product.

To have a business that sells a product, we, and then to deny those customers the use of the very word that best describes the product–that’s madness.

Jason Wojciechowski is finding it difficult to watch A’s games in this pennant race, because any failures by his favorite team are too painful. He wonders:

Given my strong suspicion that we only get one shot at life, is it better that I spend my remaining years experiencing as broad a range of emotions as I can reasonably give myself? Do the lows make the highs sweeter such that they’re worth it as a simple matter of arithmetic?

I have been similarly tempted to look away. I’ve found over the years that I’m actually a happier person when the A’s are not competitive. Winning breeds expectations, and the more your team wins, the more you expect them to win. But happiness research seems to suggest that the key to happiness is low expectations. I suspect, therefore, that unless the A’s actually win the World Series, our happiness as A’s fans actually peaked around early August, when we started to realize the A’s were a good team capable of winning, but before that winning had become so commonplace that we began to expect it.

However, I enjoy baseball on more dimensions than just winning. The game the A’s lost on Friday against the Yankees was a beautiful ballgame aesthetically: it was a dramatic game where both teams played crisp, solid baseball with good pitching. I enjoyed it immensely. Saturday’s game, however, was awful: the A’s lost, but both teams played terribly, the pitching was horrible, the defense was shaky and even the umpires got into the act with several mistakes. And that was just in the first inning before I turned it off, and went out to do something else with my Saturday. The game kept on like that, and ended up lasting almost six hours, without me. I’m glad I (mostly) missed that one.

The next three games have been equally dramatic, but somewhat in-between aesthetically. Last night’s game, for example, featured a horrible error by Brandon Moss that cost the A’s two runs, followed later in the game by a fantastic catch by Moss that saved the A’s three. For me, the drama would be much easier to watch if the A’s were not playing so sloppily.

I don’t always watch pennant race baseball, but when I do, I prefer errorlessness. Play crisply, my friends.

* * *

If you want to innoculate yourself from the pain of your favorite team losing, you can consume your sports like Will Leitch recently did, by entering the RedZone. Leitch describes his first experience watching NFL RedZone on the NFL Network:

RedZone is a commercial-free, seven-hour block of every exciting play in every NFL game all day. You see every scoring opportunity, you see every two-minute drill, you see every moment of fantasy relevance. The general consensus: You’ll never watch football the same way again.

…

On RedZone, events happen and are then forgotten in the chaos. Something that happened three minutes ago is distant history.

That, I suppose, is both the blessing and the curse of living in this information age. You can’t tell a teardrop from a raindrop in a hurricane.

* * *

Felix Salmon has an article about journalism in the midst of such massive amounts of instant information. Being able to find that teardrop in the hurricane in basically the job of the modern journalist.

But if I were hiring, the first thing I’d look at would be the prospective employee’s Twitter feed. What are they linking to? What are they reading? If they’re linking to great stuff from a disparate range of sources, if they’re following smart people on Twitter, if they’re engaged in the conversation — that’s hugely valuable. More valuable, in fact, than being able to put together an artfully-constructed lede.

The tricky balance there is to be able to both swim in the flood of information to gather the data, but to step out of it long enough to gather your thoughts.

* * *

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Jetsons, the Paleofuture has started a series to look at all 24 episodes of The Jetsons one-season run.

Thanks in large part to the Jetsons, there’s a sense of betrayal that is pervasive in American culture today about the future that never arrived. We’re all familiar with the rallying cries of the angry retrofuturist: Where’s my jetpack!?! Where’s my flying car!?! Where’s my robot maid?!? “The Jetsons” and everything they represented were seen by so many not as a possible future, but a promise of one.

The deluge of information we now experience in the real future thanks to the Internet and television is vastly different from the one we imagined when we grew up watching the Jetsons. The Jetsons’ future seems so much simpler than ours. So when we feel overwhelmed, our fight-or-flight response kicks in and we want to reject it all and run away.

As Jason says in his post above about turning off the A’s in this tense pennant race: “My gut the last few weeks appears to have made the latter choice for me, leaving me a little more time to spend with my cats, my wife, my books, and my thoughts.” Sometimes, you have to connect to the basic human needs that persist no matter what century you live in. And therein lies the dilemma of the real 21st century George Jetson: to know how to both live in the 21st century, and how to step away from it. It’s not easy.

Russell Carleton has an interesting article today on Baseball Prospectus today about the “Search for an 80 Brain“. He explores whether the difference between prospects who make it and those who fail lies in their ability to learn, and wonders if there’s a way to test those learning skills.

For one thing, it’s hard to observe a player’s learning skills, even with a really fancy stopwatch. But if the ability to learn is key to turning raw talent into actual performance, why not spend some time figuring out if the player has a 20 learning tool or an 80? Many players are drafted based on their physical tools, but what about the guy who doesn’t have blow-you-away stuff now, but can develop quickly because he can learn? In general, the closest thing that I hear to this is when scouts talk about “makeup.”

Can this learning ability be measured? My answer is “Yes… I think…”

I think so, too. But off the top of my head, I’d think there wouldn’t be one measure of learning ability, but four.

Here’s why: in order to explore how to measure learning, we need to be clear exactly what kind of learning we are talking about. Learning is about creating memories in the brain, and making those memories accessible when needed. It would be useful here to point out the two main types of memory: declarative and nondeclarative. I’ll quote from a book by Larry Squire and Eric Kandel called “Memory: From Mind to Molecules”:

Declarative memory is memory for facts, ideas, and events — for information that can be brought to conscious recollection as a verbal proposition or visual image. This is the kind of memory one ordinarily means when using the term “memory”: it is conscious memory for the name of a friend, last summer’s vacation, this morning’s conversation. Declarative memory can be studied in humans as well as other animals.

Nondeclarative memory also results from experience, but is expressed as a change in behavior, not as a recollection. Unlike declarative memory, nondeclarative memory is unconscious. Often, some recollective ability can accompany nondeclarative learning. We might learn a motor skill and then be able to remember some things about it. We might be able to picture ourselves performing it, for example. However, the ability to perform the skill itself seems to be independent of any conscious recollection. That ability is nondeclarative.

In other words, declarative memory holds conscious thought, while nondeclarative memory holds motor skills.

So let’s say we have a hitter, like Carleton’s example of Wil Myers, who is a bit too passive, and doesn’t quite swing at enough pitches. We want to make him a somewhat more aggressive hitter. How do we do that?

So it’s not a matter of merely telling Myers to “be more aggressive”. The idea of being more aggressive is a declarative memory, a conscious thought. And that declarative memory, that idea, is independent of the skill itself, of the nondeclarative memory, the motor skill required to output the desired behavior. That conscious thought needs to be translated into a motor skill. A declarative memory needs to be translated into a nondeclarative memory.

As Carleton points out in his article, this much easier said than done. The reason is that while declarative memories are under our conscious control, nondeclarative memories are not. They are created subconsciously, involuntarily and automatically. These memories are often context and emotion dependent. If you want to manipulate the nondeclarative memory system into creating the muscle memory you want, you basically have to trick it. You can trick it by repetition and practice, and/or by manipulating whatever emotions are needed, whether anger or calmness or excitement or determination.

* * *

So a scouting report for learning might look something like this:

Joe Prospect, Learning Scout Report

| declarative input | nondeclarative input | |

| declarative output | 30 | 40 |

| nondeclarative output | 50 | 80 |

Upper Left: declarative input, declarative output.

This would represent the player’s ability to repeat an instruction in his own words.

Coach: “When I say, ‘cut down on your swing’, what does that mean?”

Player at level 20: “I dunno.”

Player at level 80: “It means I shorten my stride, and bring my bat to this position here…”

This square really measures a player’s ability to coach more than it measures his ability to play. Perhaps it might also measure a player’s ability to be a catcher who can take a game plan and execute it, and to handle and communicate with a pitching staff. It can also help pitchers, not so much in the physical act of throwing a ball, but with setting up hitters and sequencing.

In general, though, this is the least important square in the matrix. Because what we’re aiming at in regards to players is the nondeclarative output, the muscle memory needed to perform at a high level. And nondeclarative input — the sensory and pattern-recognition feedback the brain gets from actually playing — is more important than the theoretical, declarative input in this square.

Upper Right: nondeclarative input, declarative output.

This would represent the player’s ability to articulate his own experiences.

Coach: “Why didn’t you swing at that pitch?”

Player at level 20: “I just froze.”

Player at level 80; “I was expecting a breaking ball away, and instead he threw me a fastball on the inside corner, and because my body was leaning out, I couldn’t adjust my balance quick enough to pull my hands in and start the swing.”

An 80-level player in this square of the matrix would be a reporter’s best friend. High skill in this area can also help a player to understand what he needs to work on, and create systematic workout procedures for improving those self-understood weaknesses. But being able to articulate what you physically experienced won’t really help you unless you also possess a high score in the lower left square.

Lower Left: declarative input, nondeclarative output.

This represents coachability: a player’s ability to take verbal or conscious ideas, and translate them into muscle memory.

A player at level 20 probably can’t even do this at all. If he learns anything, it’s only “the hard way”– by failing or succeeding himself in real situations.

A player at level 50 is someone who may need to be told something over and over until it finally sinks in. Or needs to be told something in 1,000 different ways until he finds that one mental cue which triggers the correct behavior.

A player at level 80 probably only needs to be told something once, and can immediately make the physical adjustment.

Lower Right: nondeclarative input, nondeclarative output.

This represents a player’s ability to learn from his own senses and body, from the immediate success or failure of his efforts.

A player at level 20 probably isn’t affected much by his own failures and successes. He probably repeats the same mistakes over and over again, and can’t adjust.

A player at level 50 can learn from his own failures and successes, but it takes a long time and many repetitions for those adjustments manifest themselves.

A player at level 80 probably never seems to make the same mistake or get fooled by the same pitch twice.

* * *

A single, Wonderlic-like test wouldn’t work to fill out such a matrix. You’d probably need to develop separate tests for each of the squares in the matrix. And then you’d need to collect that data for a number of years to figure out whether there is actually any sort of correlation between any of that data and the eventual success and/or failure of prospects. Sounds like a lot of work for an uncertain payoff, but it would certainly be interesting to see if there’s something there of value. The sad part is, since baseball teams keep information like this proprietary, we baseball fans will probably never know.

At the risk of committing the journalistic sin of plagiarizing myself, the time has come for me to repeat an old argument I’ve made about baseball awards.

I am repeating myself this year because of the American League Most Valuable Player race. The player who has provided the most value to his team winning in the AL has been the LA Angels’ Mike Trout, by most reasonable measurements. Measured by bWAR, Mike Trout has provided 10.1 wins to his team, followed by Robinson Cano of the Yankees at 6.8, and Miguel Cabrera of the Detroit Tigers at 6.5. Measured by fWAR, Trout is at 9.2 wins, Cabrera at 6.8 wins, and Cano at 6.3. In any case, Trout is 2 or 3 wins ahead of anybody else. His batting stats are similar to his competitors, or possibly slightly worse, but his baserunning and defense has the others beat by a mile.

But there is an argument for Cabrera, in that he is only one home run shy of winning the Triple Crown: leading the AL in home runs, RBI and batting average. If Cabrera wins the triple crown, many people are arguing that he should win the MVP, too, for this accomplishment.

This has sent many sabermetric types into apoplexy, since the Triple Crown is just an arbitrary set of statistics, and is not a good measure of a player’s value. This anger towards the support for Cabrera bothered Ken Rosenthal, who said that although he would support Trout if he had a vote, he feels that voting for Cabrera is not a unreasonable idea, and sabermetricians should open their minds a bit more.

I agree with my fellow Ken here. As I’ve said before, awards are celebrations, not measurements. It is entirely reasonable to want to celebrate the player who has provided the most fWAR or bWAR in the league. But the MVP rules are vague, and do not define what value means. There are other ways to define value. We watch baseball not because we are tools of measurement, but because we are humans participating in a culture, and we acquire emotional and social value from watching it. If our culture values an arbitrary set of stats like the Triple Crown, for whatever reason, then there is value to the team’s culture and history by reaching this achievement.

So by any meaningful measurement, Mike Trout has been better than Miguel Cabrera this year. But that doesn’t necessarily mean he has produced the season that is the most worthy of celebration. It’s quite reasonable, especially if Cabrera does win the triple crown, to vote for Cabrera.

* * *

On the flip side of the M. Cabrera coin, Melky Cabrera was today ruled ineligible to win the National League batting title. The San Francisco Giants’ version of M. Cabrera was suspended last month for testing positive for a performance-enhancing drug. At the time of his suspension, he was just one plate appearance shy of qualifying for the batting title. When that happens, the previous rule was to assume he had enough hitless at-bats to qualify, and if his batting average was still highest in the league, he would win the title. But probably because the league wanted to avoid the embarrassment of having a player who cheated win its batting crown, they decided they wouldn’t do the “add 0-fers” to his number of plate appearances, and so Melky won’t win.

Which is odd, because the batting title is a measurement, not a celebration. It’s basically a matter of math; it goes to the player who had the best batting average in the league, hits divided by at-bats. But Major League Baseball is treating it like a celebration, not a measurement, and they have decided that they don’t want to celebrate someone who cheated, so they’re invalidating his measurement. I suppose they can do that because Cabrera finished shy of the required number of plate appearances, but I wonder what they would have done if he had already surpassed the required 3.1 plate appearances per team game to qualify. Would they have invalidated it then?

For us Oakland A’s fans, this year has been a dream. Very little was expected of the team this year after GM Billy Beane traded three of the A’s best players over the winter. When the A’s lost nine games in a row in May, we fans resigned ourselves to our low expectations having been met, another disappointment in growing series of disappointments. The A’s haven’t had a winning season in five years. But in June, some magic wand was waved over the team, and suddenly everything changed. With just three weeks left in the season, the A’s are now in the lead for a wild card playoff spot, and just three games behind Texas for the best record in the American League.

I headed out to the Oakland Coliseum on Saturday to soak up some of the magic vibes. The A’s were playing the Baltimore Orioles, in the midst of a dream season of their own. The Orioles haven’t had a winning season in 15 years, but here they were tied with the hated New York Yankees atop the American League East division.

The Orioles scored single runs in the second and third innings to take a 2-0 lead. This subdued the crowd a bit, and the focus of the people around me started drifting away from the game.

In front of me sat a young boy about 8 years old. To his left was another 8-ish boy, perhaps a friend, and the friend’s younger sister and father. They boy’s mother had made a pre-game appearance and scolded him very sternly to sit nicely and behave properly while seated here with this other family, and then had left. In the top of the third one of the kids pulled out a hand-held video game console of some sort, and they began to play. The three heads all gathered around the tiny screen.

Behind me sat a row of older men and women, all probably in their fifties or sixties. One of them was wearing a Cal shirt, so I introduced myself as a fellow Cal grad, and chatted him up about his experiences at UC Berkeley. He said he graduated in ’73, which put him there at the peak of the whole protest era. He remembered walking through Sproul Plaza the day after one of these protests, the condensation from the previous day’s tear gas still dripping from the trees, stinging his eyes.

Another lady in that row then launched into a lengthy monologue. I can’t remember it word for word, but I’ll paraphrase it thusly:

My oldest daughter lives in Riverside. It’s a great place to live. It’s an hour to Disneyland on the 91, or and an hour to downtown LA on the 10 if the traffic isn’t too bad. And San Diego’s easy to get to, about an hour and a half down the 15, and you can also get to Palm Springs in an hour heading east on Highway 60. It’s fantastic.

We took a trip down there a couple weeks ago. I had surgery for uterine cancer two months ago, so the kids had been all cooped up, and you know, they needed to get out. So we headed down 101 first to Soledad, where another of my daughters lives. Her husband works in the prison there. Then we continued down 101 to Paso Robles where our oldest son lives, and then on 101 through LA to the 10 and then down the 215 to Riverside.

The day before, I had blogged about how it was an error to mistake data for function. Here was a remarkable example of avoiding that error. You’d think uterine cancer would consume a person’s life — that fighting it would become the primary function of her life. Yet this lady somehow managed to make cancer sound like merely a data point on a highway map of Southern California.

The word “cancer” has struck me with more emotional impact lately, as my brother-in-law Jim died of melanoma in August. Up until then, I had been fortunate enough not to really know anyone who had been struck down by cancer. But now having seen someone close to me suffer from it, it’s far less of an abstraction to me now, hearing about all the chemotherapy and radiation and medicines, hoping that one or some combination of these will miraculously work. Having that lady mention Paso Robles struck me double, because about six weeks before he died, Jim took a trip from his Arizona home here to the Bay Area. We watched several Euro 2012 soccer games together. Then we said goodbye, and he and his wife headed down to Paso Robles to do some wine tasting. It was the last time I saw him. There were no miracles.

The somber mood of myself and the crowd quickly reversed itself in the bottom of the third. Stephen Drew led off with a solo homer to cut the Orioles’ lead to 2-1. The boy in front of me cheered enthusiastically, jumping up and down with his arms high above his head. The crowd seemed to sense some magic happening, as the chants of “Let’s Go Oakland” grew louder and more intense as the A’s got one hit after another. When Yoenis Cespedes hit a bullet single up the middle to give the A’s a 3-2 lead, the crowd went crazy.

Chris Carter followed with a two-run double down the right field line. Cespedes read the ball perfectly off the bat, and took off running. As that powerful body flew around the bases, so fast that he nearly caught up with Josh Reddick one base ahead of him, I couldn’t help but marvel at what an amazing athlete he is. His swing and his running stride have such an lovely combination of power and grace and speed, that I couldn’t help but say to myself, “Yoenis Cespedes is a beautiful human being.” Not in the sense of him being a nice guy, since I know nearly nothing of his character, but of his body. His strong yet fluid manner seems almost the Platonic ideal of human motion.

The inning ended with the A’s ahead, 5-2, and the crowd abuzz in an intoxicating mix of joy and disbelief. As it turned out, that was all the scoring there would be. The game then marched ahead straightforwardly, without much more excitement.

As the outs piled up, the kids in front of me started getting a little bored and restless again. At one point in the 6th inning, the boy picked up some empty peanut shells and tossed them into the air.

* * *

At the exact moment the peanut shells left his fingers, his mother returned, carrying two boxes of pizza.

“What are you doing?” she shouted at him, as the peanut shells fluttered harmlessly to the floor. “I told you very specifically that you needed to behave! What the fuck is wrong with you?”

What’s wrong with him, I thought, is probably that he has a mother who is the type of person who says “fuck” to her kids.

She handed the pizza boxes to the father of the other kids, and then grabbed the boy by the wrist. “Come with me,” she said sternly. She pulled him behind her, and pulled him up the stairs onto the concourse.

Two minutes later, they returned. “Now sit down right there, don’t move, and eat your fucking pizza.”

* * *

The next morning, Craig Calcaterra blogged about a letter from the poet Ted Hughes to his son, in which Hughes explains that our true selves are childlike and innocent, but we learn through the crush of circumstances in our lives to build a shell around that inner child, to protect it from pain. It is that armor that we adults use to interface with the world.

But since that artificial secondary self took over the control of life around the age of eight, and relegated the real, vulnerable, supersensitive, suffering self back into its nursery, it has lacked training, this inner prisoner. And so, wherever life takes it by surprise, and suddenly the artificial self of adaptations proves inadequate, and fails to ward off the invasion of raw experience, that inner self is thrown into the front line — unprepared, with all its childhood terrors round its ears. And yet that’s the moment it wants. That’s where it comes alive — even if only to be overwhelmed and bewildered and hurt.

As I read this, I thought about that mom from the day before. Where does her anger come from? Was she so overwhelmed and bewildered and hurt in her childhood that the only thing she knows is to make her own offspring feel overwhelmed and bewildered and hurt, too?

* * *

The boy sat. His shoulders slumped. His head bowed. His face lost all its joy.

He took a slice of his fucking pizza. With each bite, a hard shell began to form around his soul.

* * *

I was reminded of this new anti-alcohol video from Finland:

My dad had an alcohol problem when I was growing up. I was fortunate in that when my dad got drunk, he didn’t become abusive. He merely became the world’s worst standup comic. Still, as a child, you’re bewildered by it. Embarrassed. You try to ignore it, forget about it, put a shell around yourself and block it out.

Eventually, my mom had enough and divorced my dad. My dad remarried. Eventually, about the time I was a senior in high school, the drinking got to the point where he couldn’t eat if he drank. The food would just get stuck in his throat. I could see that same bewilderment, that same embarrassment in his new wife’s eyes, that I knew so well.

One day, after another one of these episodes, I found him alone in the basement. I walked up to him and said, “You’re going have to choose. Which do you love more, your bottle or your wife?” Up until that day, I had never said a word about his drinking, ever, in my life. He looked at me, speechless. I turned around and walked out.

I walked into that basement a hurt child, and walked out a man. I decided that this cycle of pain was going to end, right there, with me. Any family I had was not going to have to deal with this same kind of crap I had to deal with. That’s why I don’t drink alcohol.

Shortly after our confrontation, my dad quit drinking, cold turkey. Never drank another drop of alcohol the rest of his life. Our relationship got so much better after that. I am so grateful.

I’m sure I’ve missed out on a lot of socializing by not drinking. You don’t invite the guy who doesn’t drink out for beers with the guys. Fortunately, I’m an introvert, so missing out on socializing doesn’t really bother me at all. Pity the poor extrovert who has to make the same decision.

* * *

The boy now in submission, her damage done, the hurricane of a mother departed the scene as abruptly as she arrived. She was not seen again for the rest of the game.

* * *

The outs pile up, three outs here, three outs there, and eventually, the game is over. But that boy and I, we had that one moment together, didn’t we, that raw, magical, miraculous moment where Chris Carter hit that double down the right field line, where Yoenis Cespedes flew around the bases and almost caught up to Josh Reddick, and we broke through our shells and forgot our pain and fears and we marveled and cheered and threw our arms up in the air, each of us free as an uninhibited child.

As Apple announces the iPhone 5 today, I want to make a confession. It’s a bit embarrassing for someone like me who has spent his career in high tech, but here goes: I don’t have a cell phone.

At first, my reason was this: I lived and worked and played on a very flat island with no tall buildings, so coverage was awful. I had reception in only one room of my house, not at all in my office three blocks away, and spotty reception where I play indoor soccer. I spent 95% of my time at those three places, and I wouldn’t be getting what I was paying for. When I went out somewhere that coverage was better, I’d borrow my wife’s cheap pay-as-you-go phone, and my needs were met.

The cell phone service providers made a mistake. They gave me an opportunity to learn that I could live without them.

* * *

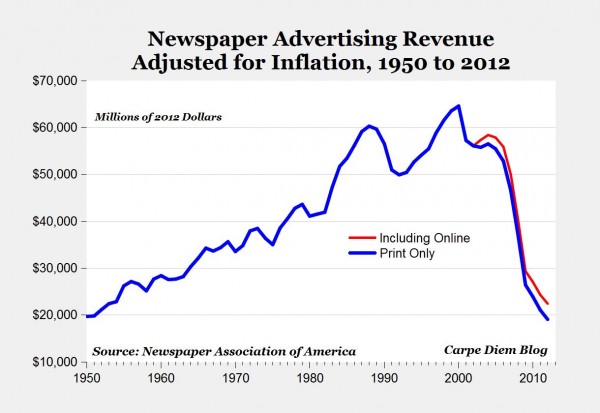

This is the image of an industry suddenly collapsing.

Why did the newspaper industry suddenly collapse like that? Because it got hit from two sides at once by the Internet. Craigslist and eBay took away their classified ad business, while blogs and online news sources directed their readership elsewhere for the same information. Newspapers might have been able to handle a one-front battle, but a two-front battle was catastrophic.

But there’s something else that hurt the newspaper industry: the indirect nature of their feedback loop. It’s a business model that provides a service to one group of people, while taking money from a different group of people.

The best kind of feedback for a business is revenue. If your revenue increases or decreases, you’re going to notice. But when the users of your product aren’t providing the revenue for your product, your feedback loop has a natural delay to it. The people who give you revenue might lead you to innovate (or not) in a direction your users won’t like, and you won’t notice that you’re making a mistake because it takes a while for that problem to reach your bottom line. So you react too slowly, and that slowness can be fatal.

* * *

In fact, all businesses that rely on advertising have this problem. Their users want one thing, and the revenue generators want something different. So if a company like Facebook starts alienating their customers in an effort to maximize their revenues, they may find themselves not just the subject of an Onion parody, but ruining their business before the bottom line has time to let them know they’ve made a mistake.

* * *

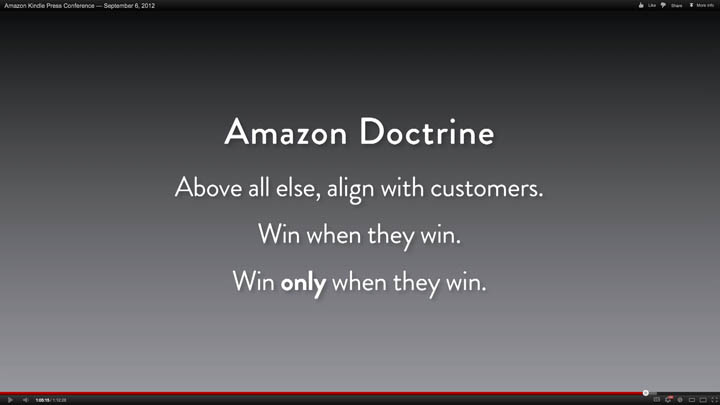

Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos is a very smart man. He understands this problem. He knows that the key to keeping ahead of the rapid pace of high-tech change is to master the feedback loop between what his customers want next, and what his company makes next. That’s why in his Kindle press conference last week, he laid out this doctrine:

Think about the major players in high tech right now: Microsoft, Google, Facebook, Twitter, Amazon, Apple. Which of these has their revenues most directly aligned with what their customers want? It’s probably in roughly this order:

Amazon/Apple

(gap)

Microsoft

(gap)

Google

(gap)

Twitter/Facebook.

Amazon and Apple sell most of their products directly to their users. When their customers buy something they make, they know the product is good; when they don’t buy, they know immediately they made a mistake. Microsoft doesn’t sell directly to users– they sell to distributors and OEM manufacturers, so there’s noise injected into their feedback loop, and they land just a little lower on this spectrum. Google sells ads, but their ads are often directly related to what the customer wants; if someone is searching for jeans, they get an ad for jeans. Sometimes the ad happens to be exactly what the user wants.

Twitter and Facebook, on the other hand, need to inject their ads into an environment where the users wouldn’t really want to see ads at all if they didn’t have to. This leads to customer dissatisfaction, expressed not just in the Onion parody above, but also in a real-life alternative social networks like App.net who are trying to sell directly to users.

* * *

My favorite product of all is probably Major League Baseball. I consume a lot of Major League Baseball. But MLB is going in a very tempting, but dangerous direction. When MLB began, a vast majority of their revenues came from the product their users consume. They sold tickets to the games, and that’s how they made their money. But more and more of MLB’s revenues are coming from indirect sources.

At a local level, if you’re a team like the Oakland A’s, who play in an antiquated stadium that doesn’t generate a lot of revenues, a big proportion of your money comes from TV and league-wide revenue sharing. So you can do things over a number of years, like threaten to move away and trade away favorite players, that damage your brand but aren’t directly noticeable in your bottom line. Ownership may not even know how much their fans hate them, because their loyalty to their local team keeps them around despite their dissatisfaction. But eventually, there may be a straw that breaks the camel’s back. Los Angeles Dodger fans may have hated owner Frank McCourt for years, but it was only in the last year of his tenure that the dissatisfaction actually became truly noticeable in attendance figures. The feedback loop in baseball has quite a long delay.

In recent years, baseball’s misalignment problem has accelerated almost exponentially. Like the newspaper industry, the source of this change is new technology. Unlike the newspaper industry, however, the change has caused MLB’s revenues to increase, not decrease, dramatically.

The reason for this change is twofold:

- The DVR allows people to skip through commercials on TV. This makes live events, which people can’t skip through, a much more valuable delivery mechanism for advertising.

- Internet video allows people to watch television shows and movies without subscribing to any sort of cable or satellite TV service. Cable/satellite may or may not be shedding customers at the moment, but it’s certainly not growing much, and without sports would almost certainly be shrinking. This makes sports networks extremely important to cable and satellite providers: without them, most people will eventually learn to do without cable TV, and just get all their content from the Internet.

So this sets up a strange mismatch between what MLB customers want, and what their revenues tell them to do. MLB fans want to watch their favorite team on whatever device they prefer. But MLB’s revenue stream is depending more and more on their customers NOT being able to watch their team over the internet, forcing them to watch on TV.

MLB’s revenues come less and less directly from baseball fans, and more and more indirectly, from TV networks and cable/satellite providers.

This causes MLB to lose control over the customer experience of their fans. If a TV network and a cable provider can’t come to an agreement on price, for example, Padres fans can go a whole season without being able to watch their team on TV. And if not all TV networks are available on all cable/satellite services, fans have to scramble around to watch the games they want.

Or, fans just go without. And what does that do? It ends up teaching them that they can learn to live without your product. That too, may not be noticeable right away, until it snowballs too late for you to do anything about it.

* * *

But you can’t really blame MLB, can you? If you’re the Los Angeles Angels and someone wants to pay you $3 billion dollars over 20 years for your TV rights, do you turn that down? No, probably not.

In expectation of an even larger payday than the Angels got, the Los Angeles Dodgers recently sold for $2.1 billion. Given that the estimated value of the Dodgers just a year before that was about $800 million, over 60% of the value of the franchise lies in that regional TV deal.

But think about that for a second. The new owners of the Dodgers spent $1.3 billion dollars on a business model that:

(a) depends almost entirely on another industry that isn’t growing, and would be in steep, steep decline without your industry. If either one of your industries catches a cold, the other one will necessarily start sneezing.

(b) puts your industry in a complete misalignment with your customers, requiring you to prevent your customers from consuming your product in the way they’d prefer, distancing yourself from the revenue feedback loop, making it more difficult to know if you’re doing any long-term damage to your product, and where you need to improve.

The new Dodger owners obviously didn’t care. Maybe they didn’t think about these risks. Or maybe they did, and thought the math worked anyway. Or maybe they considered it, but they thought they could sell the team to someone else before the whole house of cards fell in, like an investor in a Ponzi scheme who doesn’t think he’ll be the one who ends up being the victim.

Who knows. But me, I wouldn’t touch a business model like that with a 10-mile pole.

Only when the future arrives does the past become clear.

* * *

One hundred years ago, on April 10, 1912, the RMS Titanic left Southampton, England on a voyage for New York City. It never arrived.

Ten days later, baseball opened its newest ballpark, Fenway Park. At the time, Fenway Park had no history. No Babe Ruth, no Ted Williams, no Yaz, no Fisk, no Buckner, no Dave Roberts, no bloody sock. It was a blank slate of exciting possibilities.

* * *

In 1980, I was living in Sweden with my mom. I was 14. My dad was living in California. For the summer, my mom let me go on a plane voyage, by myself, across the Atlantic Ocean, to spend the summer with my dad. I managed to change planes at JFK Airport in New York, and not get lost. It was exciting. I felt like an adult.

* * *

On April 11, 2001, I attended a baseball game at the Oakland Coliseum between the Oakland A’s and the Seattle Mariners. It was not technically the first game of the season for the A’s, or the Mariners, or the Mariners’ new imported outfielder, Ichiro Suzuki. But in my memory, it may just as well have been. Because that was the game where Ichiro arrived.

One play — one — made us all just stop, gasp, and say, “Whoa. Whoa! This guy is something special.”

I don’t have a photographic memory, but for that one play, Ichiro throwing a laser beam from right field to third base to throw out Terrence Long, my brain has decided to make an exception.

I can still see it quite clearly in my mind. Although now, after Ichiro’s long career, it means something quite different to me than it did back then.

* * *

Yesterday afternoon, April 6, 2012, my teenage daughter decided to go out with some friends. They didn’t have any specific plans.

At some point, she and her friends decided to go see the movie Titanic 3D.

At no point, did it occur to her to contact her parents and let her know of this decision.

At 8pm, we sent her a text message. Where are you? “Oh, at the theater. The movie’s about to start.”

* * *

At no point when I was travelling across the Atlantic Ocean by myself as a 14-year-old did it occur to me to think how my mom must have felt while she was waiting for me to call and let her know I had arrived.

The whole time, she probably feared the worst. She probably feared the Titanic.

* * *

Last night, April 6, 2012, there was yet another ballgame at the Oakland Coliseum between the Oakland A’s and Seattle Mariners. It was not the first game of the season for M’s and their old imported outfielder, Ichiro Suzuki, or the A’s and their new imported outfielder, Yoenis Cespedes.

But again, it may just as well have been. For there was, again, an arrival.

Gasp. Yoenis Cespedes absolutely destroyed that baseball.

* * *

When my daughter finally arrived home, at nearly midnight, we talked.

We did not talk about Yoenis Cespedes. We did not talk about how my mom felt when I flew across the Atlantic by myself three decades ago.

I said words that will probably not be fully understood for three decades hence, when it is my daughter’s turn to say them, to her own offspring.

* * *

The world will little note, nor long remember, who won the two ballgames which marked the arrivals of Ichiro and Cespedes. But those games will span generations. Fans may not now fully appreciate what Yoenis Cespedes did last night, or what it really means. But 11 years from now, as it did 11 years ago, some new star will burst forth, and we’ll finally realize what this special night was really all about.

Yesterday, the San Francisco Giants opened a Giants Dugout Store in the suburb of Walnut Creek. Why is this worthy of note? Well, take a look at where this store is:

That’s deep in the center of Contra Costa County, one of only two counties that are, by MLB definition, the territory of the Oakland Athletics.

That in itself wouldn’t be such a big deal if the Giants were not also making the argument that letting the Oakland A’s move to San Jose is a violation of their territorial rights to Santa Clara County, and should therefore not be allowed.

This is not the first time the Giants have stepped on the A’s turf. When the Giants won the World Series in 2010, they paraded their trophy all around the Bay Area, including two cities in Contra Costa County: Walnut Creek and Richmond. But their parading did seem to carefully avoid any city in Alameda County.

Meanwhile, though, the Giants are still resisting the A’s move into “their” territory of San Jose:

- They have created and funded a “grassroots” movement against the A’s stadium in San Jose, which just on Friday filed a lawsuit against the San Jose ballpark.

- For similar reasons, they have enticed their own ballpark sponsor, AT&T, who happens to own a parcel of land needed to complete the San Jose ballpark, to flat out refuse to sell that parcel at any reasonable price, thereby forcing the city to engage in a complicated eminent domain procedure to get the parcel secured.

- They have purchased San Jose’s minor league team, thereby doubling up on the “territorial rights” argument, and ensuring that a negotiation over compensation must be completed before the A’s can build their ballpark.

So what gives? Why are the Giants still behaving like territorial rights are sacred in “their” Santa Clara County, but like they don’t matter in the A’s Contra Costa County?

Perhaps the Giants Dugout Stores are a separate corporation from the Giants themselves, and are therefore not covered by the territorial rights, but if so, that’s just a legalese cover story. These two entities are tied at the hip. You know the Giants could have just said the word, and there would not have been a Giants Dugout Store in Walnut Creek.

So what’s really going on here? I can think of two explanations that make some sense. Either:

- A swap of Contra Costa County for Santa Clara County between the Giants and the A’s is a fait accomplit. There are t’s to cross and i’s to dot, but that’s eventually going to happen. Any resistance the Giants are showing now towards the A’s moving to San Jose is all about leverage: how much money will the Giants get in compensation for the loss of their territorial rights?

One argument for this interpretation is that the A’s themselves haven’t complained one peep about this store, and they didn’t complain about the trophy parading, either. If there was no such tacit agreement, and I were the A’s, I’d be raising holy hell about the existence of this store.

Or: - The Giants have launched a full-out war against the A’s. They intend to do everything they can to force the A’s out of the Bay Area while they have the chance.

In this scenario, the Walnut Creek Dugout Store is a beachhead to push the A’s out of town. They attack the A’s from the west as usual, and from this Dugout Store, they launch a propaganda campaign to weaken the A’s support from the east. And from the south, they employ every possible legal maneuver and manipulate every single sock puppet they can to prevent the A’s from moving to San Jose.

The argument for this scenario is that this is the scenario that produces the best possible financial outcome for the Giants: the A’s leaving the Bay Area. The A’s would be stuck in the Coliseum with dwindling fan support and nowhere else to go but to some other metro area that can build a stadium for them. For the Giants shareholders to maximize the return on their investment, this is the optimal strategy to take.

In either case, though, the territorial rights argument is now over.

In the first scenario, it’s over because the Giants have given up. The Walnut Creek store is about launching a new marketing campaign to win over the new set of fans that they ‘acquire’ in exchange for the A’s moving to San Jose.

In the second scenario, then the Giants Dugout Store in Walnut Creek invalidates the whole “we just want the A’s to respect our territorial rights” argument as just bullshit. The Giants don’t really believe in, care about, or respect territorial rights at all. Instead, the Giants actually only care about pushing the A’s out of the Bay Area entirely. They want the whole Bay Area market to themselves, so they can make a lot more money when they eventually sell the team.

It was former A’s owner Walter Haas who let the Giants have Santa Clara County in the first place, when the Giants were trying to build a stadium down there themselves. He did that because Haas always had the bigger picture in mind: both sports and businesses do not just exist for profits alone; they are an essential part of the fabric of our communities. Anyone who walks on the UC Berkeley campus and sees the Haas name all over the place knows he believed that deeply. Capitalism works best when capitalists understand that their businesses aren’t islands unto themselves. When corporations live for profits and profits alone, you end up with people occupying Wall Street.

I’m hoping that Scenario #1 is closer to the truth than Scenario #2. It would be extremely disappointing if it wasn’t. Giants CEO Larry Baer was actually once a board member of one of the companies I helped found, and I had always respected him before. I’d like to think he, as a former Cal grad, is capable of a Haas-like vision that extends beyond just the corrosive idea that ‘maximizing shareholder value’ is the sole purpose of a corporation.

Normally, I’d just give the benefit of the doubt to the Giants, assume innocence until proven guilty, and that Scenario #1 is likely the truth. But doing so in this case requires me to believe facts not in evidence. It requires me to interpret the A’s silence as acceptance. The only facts that have been presented publicly involve the Giants aggressively moving against the A’s desires and interest, and the A’s just shutting up and taking it. I have no idea what is going on behind the scenes. So therefore, I don’t know quite how to interpret this.

The arguments are done, and the jury has the case. Is the Giants move into Walnut Creek a benign marketing play, or an act of malign selfish corporate greed? We anxiously await the verdict.

Chapter 10 of Daniel Kahneman’s book Thinking Fast and Slow covers familiar ground to anyone who follows sports statistics. The chapter addresses two of the major mistakes humans make when dealing with statistical informtion: ignoring small sample sizes, and seeking out patterns in outcomes that are actually random chance.

At one point, he discusses the “hot hand theory”, where it is shown that basketball players do not actually have streaks where they get hot; the streaks we observe are pretty much what we would statistically expect from a random distribution of shots, given a player’s overall shooting percentage.

That, too, is familiar territory to people who follow sports statistics. But recently, I came across something new (to me, anyway) about this topic. What has been missing from the discussion is an explanation about why the outcomes of human performance is distributed randomly.

Suppose you had a very precise pitching machine. It throws the exact same pitch to the exact same location every single time. And yet, a human batter facing that machine and those pitches would not hit the ball with the exact same result each time. Why not?

You might just chalk it up to, “we’re humans, not robots.” But that’s not really an adequate explanation, is it? Which part of human mechanics introduces the randomness in our performance?

A good explanation for the randomness in our performance can be found in this Ted Talk by Daniel Wolpert. At about five minutes in, he explains that the chemical transmission of nerve signals from our brains to our muscles and back is extremely noisy.

When we use a machine metaphor to describe our bodies, we make assumptions about our systems that aren’t accurate. The signals that our bodies send aren’t nearly as clean as the electronic signals our computers send to its peripheral devices.

Think about someone you know who is hard of hearing. Or about having a conversation in a noisy restaurant. What happens in those conversations? Often you can’t hear every word, so you have to make a guess based on context as to what was actually said. You are forced to fill in the gaps with guesses based on past experience. And sometimes those guesses are wrong.

And because the noise disrupts the signals randomly, our guesses are wrong randomly. If we could somehow replace our nerves with copper wires or fiber optic cables, though, our performance failures would be reduced significantly.

I got a Kindle today, and one of the first books I bought was Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman. I don’t think I’ve ever looked forward to a book more than this one, a summary of how the human mind works by the leading scientist in the field. I plan on making some notes on this book as I read it.

Here’s the first one. Yesterday, I wrote this on Twitter, about the Oakland A’s hiring of Chili Davis as their new hitting coach.

I approve of Chili Davis as A’s hitting coach, since I liked him as a player & I have no other way to know what makes a good hitting coach.

Right in the very first chapter, Kahneman discusses this kind of mental error. He describes an executive who decides to buy Ford stock because he likes Ford cars. He doesn’t take into consideration at all whether the stock is currently priced correctly.

The executive’s decision would today be described as an example of the affect heuristic, where judgments and decisions are guided directly by feelings of liking and disliking, with little deliberation or reasoning.

Kahneman goes on to explain that when we lack the skills to answer a question, what we often do is answer a different question instead. I don’t have the skills or knowledge to know whether Chili Davis would be a good hitting coach. But I know the answers to some other similar questions. Was Chili Davis a good hitter? Yes! Was Chili Davis a likable player? Yes!

So my mind naturally decides to substitute the answers for the questions I can answer for the question I can’t. And the odd thing is, we often don’t notice ourselves that we’ve performed this question substitution, so we often feel very confident in our answers, without just cause.

I feel very happy about the choice of Chili Davis as the A’s hitting coach. I feel quite confident that he will do a great job. Logically, I know that this is just a kind of cognitive illusion. But knowing how the trick works doesn’t seem to make the trick stop working. I still feel happy and confident about Chili Davis as the A’s hitting coach.

There are few characters in all of literature more evil than Shakespeare’s Richard III. In the very first scene of the play, Richard comes right out and declares that he is a villain. He then proceeds to spend the rest of the play alternating between describing the evil he’s about to do, and doing that evil. He cares nothing about the damage he does to the people around him. He murders anyone who gets in his way: his enemies, his friends, his closest ally, his brother, his wife, and his two nephews–both children. He’s a monster.

Yet he’s also intelligent and, in the hands of a good actor, both charming and funny. I recently saw Kevin Spacey perform in Richard III at the Curran Theater in San Francisco. At times, Spacey’s impeccable comic timing had the audience in stitches.

It was both an amazing and a disturbing performance. The play would have no life, no value, if it were just a laundry list of evil actions. But, thanks to the genius of Shakespeare, and the talents of an accomplished actor, we find ourselves entertained by evil, impressed by evil, charmed by evil, laughing at evil, laughing with evil. We, the audience, can’t help ourselves.

What does this say about us? Does our ability to enjoy evil condemn us as evil ourselves?

* * *

What, dost thou scorn me for my gentle counsel?

And soothe the devil that I warn thee from?

O, but remember this another day,

When he shall split thy very heart with sorrow,

And say poor Margaret was a prophetess!–Queen Margaret, in Shakespeare’s Richard III, Act I, Scene III

Only one character in Richard III recognizes from the start that Richard is a bad man: old Queen Margaret. She had suffered this kind of treachery before. But when she tells people about the evil before them, nobody chooses to consider she might be right. They dismiss her as just a crazy old lady. Nobody really wants to confront such an uncomfortable idea. And so an evil man continues to roam free, to do more damage to people’s lives.

Sound familiar?

* * *

“You manage things. You lead people. We went overboard on management and forgot about leadership.”

Grace Hopper was one of the pioneers of computer science. She is credited with coining the computer terms “bugs” and “debugging”. One of the bugs she felt had crept into late 20th century society was that our educational institutions stopped teaching leadership, and started teaching management instead.

If you think about her quote in relation to the Penn State scandal, you can easily see how this thing went wrong. When organizations get large, when millions and billions of dollars are at stake, human beings become abstractions. People aren’t people anymore. They’re assets, or resources, or targets, or obligations, or liabilities, or potential lawsuits.

This thing at Penn State went horribly wrong because this thing became a thing. It became something to manage, an issue to deal with. And every time the buck got passed along the management chain, the issue became less person-like and more thing-like.

Penn State failed because they had management, not leadership. They had managers, not leaders. They failed because they didn’t have anyone who could tell the difference.

* * *

It’s very de-motivating to work in an environment where you can see all the brutal facts, but those in power are not confronting those brutal facts. And you want them confronted because you want to be part of something great.

—Jim Collins, on “How the Mighty Fall”, his study of how great enterprises unravel.

Evil is repulsive. So it’s natural to want to repel it, to look away, to ignore it, to hope it’s not really there, to hope it will go away. Shakespeare recognized that human behavior 500 years ago. We’re still just as human today.

But the only way to defeat evil is to not repel it too quickly. If you dismiss or rationalize away the brutal facts you face, you only displace those brutal facts temporarily. They’re still there, lurking in the background.

Wise leaders must have the courage to let that evil in, just long enough to examine it, to understand it. That’s dangerous. You don’t want to be seduced by the temptations of evil yourself, and you don’t want to become a victim of it. But it must be done. It is wise, not evil, to want to study the likes of Richard III. It is wise to try to take lessons from the failures at Penn State. Otherwise, there will certainly be more victims whose hearts are split with sorrow.

In my previous job, I built a big database of zipcodes and geolocations, and distances between those zip codes. The server that this database lived on is getting shut down sometime in the next 24 hours. A couple days ago, I suddenly realized I could use that database to answer a few questions I’ve had about where the A’s should be moving.

So I’ve been scrambling to try to get some queries done, before the server goes away. I managed to get the work done once, but I didn’t get a chance to double-check anything, so take all this with a gigantic grain of “this is a first draft” kind of salt.

* * *

The raw data I had was from the 2000 census and included:

- every 5-digit zip code in the United States (about 40,000 of them)

- the latitude and longitude of each of those zip codes, and

- population and median household income for about 30,000 of those zip codes

I’m not sure why 10,000 zip codes don’t have population and income data. Probably some of them represent entities (like governments and such) that aren’t geographic locations with residents. But not all of them. For example, the zip code that includes Safeco Field in Seattle was among the zip codes missing data. Baltimore looks like it’s missing a big chunk of data. Plus, there’s no Canadian data either, so the Blue Jays are unrepresented, as are probably some additional Tigers and Mariners fans. So I’m sure the data needs a real good scrubbing, so I’ll repeat my warning about the rough nature of this data.

From the geodata, I calculated the distance between any two zipcodes that were less than 150 miles apart.

* * *

If you’re going to build a ballpark somewhere, you’d want to put it somewhere:

- with as many people as possible

- who have as much money as possible

- who live as near to the ballpark as possible

So I came up with a formula to reflect this. For this exercise, I don’t really need to know the exact amount of money a ballpark can generate, I just need a number I can use to compare with. So median household income will do just fine, even though it’s not at all an accurate representation of how much money is available to spend on baseball.

So here’s what I did: For each zip code within 75 miles of a MLB ballpark, I took the population and multiplied it with the median household income of that zipcode, to give that zipcode a total amount of money for that zipcode. (I should probably have divided by average household size, but we’re after relative comparisons here, so it doesn’t matter too much.) Then for each mile that zipcode was from the ballpark, I subtracted 1/75th of that total from the score for that zipcode.

So the closer the zipcode is to the ballpark, the more money from that zipcode is assigned to the team.

Then I repeated the exercise for five potential A’s homes: the Coliseum, Victory Court, Fremont, San Jose, and Sacramento.

Once I had done that, I did it for every minor league park that was more than 75 miles from any existing MLB park, plus Portland, Honolulu, and Anchorage.

* * *

The (rough) results, for your viewing pleasure:

| zip | team | city | state | relative market size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10451 | Yankees | Bronx | NY | $ 752,743,595,112 |

| 11368 | Mets | Corona | NY | $ 748,642,916,914 |

| 90012 | Dodgers | Los Angeles | CA | $ 510,586,706,490 |

| 92806 | Angels | Anaheim | CA | $ 429,295,980,560 |

| 60616 | White Sox | Chicago | IL | $ 353,523,094,940 |

| 60613 | Cubs | Chicago | IL | $ 351,956,542,055 |

| 19148 | Phillies | Philadelphia | PA | $ 313,899,514,792 |

| 20003 | Nationals | Washington | DC | $ 313,043,794,378 |

| 94107 | Giants | San Francisco | CA | $ 276,531,798,517 |

| 02215 | Red Sox | Boston | MA | $ 258,052,953,191 |

| 48201 | Tigers | Detroit | MI | $ 194,991,345,880 |

| 76011 | Rangers | Arlington | TX | $ 184,979,524,329 |

| 77002 | Astros | Houston | TX | $ 184,030,914,939 |

| 30315 | Braves | Atlanta | GA | $ 166,992,030,231 |

| 55403 | Twins | Minneapolis | MN | $ 138,398,423,288 |

| 33125 | Marlins | Miami | FL | $ 134,237,186,849 |

| 85004 | Diamondbacks | Phoenix | AZ | $ 126,863,473,073 |

| 98134 | Mariners | Seattle | WA | $ 123,032,784,722 |

| 80205 | Rockies | Denver | CO | $ 120,203,857,817 |

| 92101 | Padres | San Diego | CA | $ 119,511,331,778 |

| 44115 | Indians | Cleveland | OH | $ 114,814,235,603 |

| 53214 | Brewers | Milwaukee | WI | $ 114,411,126,303 |

| 63102 | Cardinals | St. Louis | MO | $ 95,088,871,967 |

| 45202 | Reds | Cincinnati | OH | $ 93,961,385,672 |

| 15212 | Pirates | Pittsburgh | PA | $ 91,812,365,763 |

| 33705 | Rays | St. Petersburg | FL | $ 86,162,065,166 |

| 64129 | Royals | Kansas City | MO | $ 75,617,221,577 |

| 21201 | Orioles | Baltimore | MD | $ 51,550,959,511 |

| 94621 | Coliseum | Oakland | CA | $ 302,835,904,135 |

| 94538 | Fremont | Fremont | CA | $ 301,356,267,461 |

| 94607 | Victory Ct | Oakland | CA | $ 288,464,089,740 |

| 95110 | San Jose | San Jose | CA | $ 244,281,690,385 |

| 95691 | Sacramento | West Sacramento | CA | $ 122,189,968,456 |

| 97205 | Portland | Portland | OR | $ 86,934,977,194 |

| 43223 | Columbus | Columbus | OH | $ 82,466,829,644 |

| 48912 | Lansing | Lansing | MI | $ 80,674,718,903 |

| 46225 | Indianapolis | Indianapolis | IN | $ 76,724,547,759 |

| 29715 | Charlotte | Fort Mill | SC | $ 66,474,729,100 |

| 27401 | Greensboro | Greensboro | NC | $ 61,196,329,994 |

| 23510 | Norfolk | Norfolk | VA | $ 58,754,813,183 |

| 14020 | Batavia | Batavia | NY | $ 58,698,864,009 |

| 78664 | Round Rock | Round Rock | TX | $ 57,730,378,193 |

| 78227 | San Antonio | San Antonio | TX | $ 57,705,434,009 |

| 27597 | Carolina | Zebulon | NC | $ 56,677,487,954 |

| 49017 | Southwest MI | Battle Creek | MI | $ 54,991,532,182 |

| 27105 | Winston-Salem | Winston Salem | NC | $ 54,919,270,523 |

| 14608 | Rochester | Rochester | NY | $ 54,337,641,491 |

| 89101 | Las Vegas | Las Vegas | NV | $ 53,809,399,974 |

| 37203 | Nashville | Nashville | TN | $ 53,707,382,854 |

| 49321 | West Michigan | Comstock Park | MI | $ 53,532,262,868 |

| 84058 | Orem | Orem | UT | $ 52,659,523,005 |

| 70003 | New Orleans | Metairie | LA | $ 51,061,101,559 |

| 40202 | Louisville | Louisville | KY | $ 50,940,204,646 |

| 14203 | Buffalo | Buffalo | NY | $ 50,893,985,379 |

| 32114 | Daytona | Daytona Beach | FL | $ 48,253,823,630 |

| 18505 | Scranton-Wilkes | Scranton | PA | $ 47,728,598,665 |

| 23230 | Richmond | Richmond | VA | $ 47,551,291,211 |

| 32940 | Brevard County | Melbourne | FL | $ 47,518,011,693 |

| 84401 | Ogden | Ogden | UT | $ 46,138,307,179 |

| 38103 | Memphis | Memphis | TN | $ 44,483,924,752 |

| 13021 | Auburn | Auburn | NY | $ 43,555,185,837 |

| 29607 | Greenville | Greenville | SC | $ 43,508,445,289 |

| 91730 | Rancho Cucamonga | Rancho Cucamonga | CA | $ 39,638,600,052 |

* * *

These results, outside of Baltimore, smell more or less right to me.

Next, though, I tried to put some measure on what happens to a market when it is shared between teams. This is where the results surprised me, enough so, that I think I probably screwed up somewhere.

I’ll address that in an upcoming blog post.

Sam Miller gets my nomination for Sentence Fragment of the Year, for this line in a hilarious piece of baseball satire:

Cubs Chairman Tom Ricketts: … and that’s how I diced up Alfonso Soriano’s contract, bundled it with other toxic assets, and sold it to public employee pension funds.

I love how that line so concisely skewers both the left and right side of the political aisles for their roles in the current screwed up state of our economy.

…and it’s not even a full sentence!

* * *

I’m beginning to think that the future of politics will be like the future of warfare where people won’t fight people anymore; one side’s robots fights the other side’s robots, and whoever’s robot wins, wins.

In politics, each side hires sabermetricians, and the sabermetricians argue each other to the death before they proceed further. People in politics will have to know how to defeat a sabermetrician in an argument, otherwise they’ll suffer the fate of (oxymoron alert) poor Warren Buffett, running into a uppercut from Phil Birnbaum.

* * *

And speaking of baseball and pension funds, Moneyball author Michael Lewis has a new piece in Vanity Fair called “California and Bust.” In it, he interviews San Jose mayor Chuck Reed. I assume when Lewis met Reed they discussed San Jose’s attempt to woo the A’s, but nothing on that topic appeared in the article. The whole article made me pessimistic that any city anywhere in the country could afford to actually get a stadium built for the A’s, but heck, what do I know? Maybe that’s what’s taking Bud Selig so long to decide the A’s fate; it takes time to find a city that can dice up the stadium costs, bundle them with some toxic assets, and sell them back to Wall Street to complete the circle.

It’s been two years since Baseball Toaster shut down. On the first anniversary, that final day felt like it was only yesterday. Now, it feels like a lifetime ago. Not sure why, but maybe it’s because I’ve completed all the things I quit the blogging scene to accomplish.

Now as that checklist is finally done, and I’m trying to figure out what next to do with my life, I find myself drifting back to my old scene. Today, for example, Toaster alumnus Josh Wilker has a blog entry that compels me to respond with a little story.

* * *

After Toaster, I decided to take a sabbatical from baseball. Stopped watching it on TV, stopped going to games, stopped playing fantasy baseball, and only read about it minimally. I wanted to stop doing so many things half-assed, and give full concentration to my other priorities in life. Plus, my four years of running the Toaster had burned me out on baseball for a while. I needed a break.

That summer, I took a trip with my family to Sault Ste Marie, Michigan. Some good friends of ours in the Coast Guard had been stationed there. It’s a long trip. It took us longer to get there, door-to-door, than it takes me to get to my brother’s home in Sweden. There aren’t any direct flights to Detroit from Oakland, so we took a roundabout flight that stopped in Ontario (the California one) and Phoenix before arriving in Detroit. We then rented a car and drove an additional six hours to get there. Our friends’ home was literally off the last exit in the United States. Miss that offramp, and you end up in Ontario (the Canadian one).

When you’re a six-hour drive from the nearest major airport, you feel like you’re in the middle of freakin’ nowhere. All your cares back home might as well be on the moon, you’re so far from anything you’re familiar with.

One day, we take a trip to nearby Fort_Michilimackinac. While touring the fort, we come across this Native American gentleman giving a demonstration on how the local tribes worked deer hides: