Note: this page will change every time you reload it.

Note: this page will change every time you reload it.

The publishing date on these blog entries are mostly a fiction. I write the blog entry’s date as being the same as the game I’m writing about, but most of the time, I’m actually writing these blog entries the following morning.

This time, the world kind of changed the “following” morning. First, one of my kids woke up with a sore throat, a headache, and body aches. Another one woke up sneezing.

And just as I was writing this the Milwaukee Bucks decided not to play their NBA playoff game today, to protest police violence.

As I went to bed last night, I thought, maybe I’ll actually do some baseball analysis in the next blog entry for a change. Maybe break down Sean Manaea, because I find his struggles (or not) fascinating. Maybe dig into the A’s struggles with runners in scoring position.

But now, not so much. Everything is different now. I don’t really care much about writing about the A’s 10-3 victory over the Rangers.

I committed to writing about this season when I had nothing better to do, but there are higher priorities now. We have to care for the sick among us, without somehow getting sick ourselves. That will take some doing.

I’m not giving up on this blog, but it’s no longer a commitment. I’ll do it if I have time and energy, but skip it if I don’t. I’m sure you understand.

At 1:12pm PT on Wednesday, August 26, 2020, word came out that the Milwaukee Bucks decided not to play their NBA playoff game against the Orlando Magic, in protest against the police violence in Kenosha, Wisconsin. At 1:43pm PT, the Houston Rockets and Oklahoma City Thunder also decided not to play. At 2:05pm PT, the NBA announced that all playoff games that day would be postponed.

At 2:59pm PT, MLB’s Milwaukee Brewers decided not to play their 5pm PT game against the Cincinnati Reds. At 4:06pm PT, the Seattle Mariners decided not to play their 6pm PT game against the San Diego Padres.

At 3:35pm PT, Bob Melvin was asked if the A’s had discussed not playing. He said they had not.

The A’s and Rangers played the game. The A’s won 3-1.

After the game, Melvin was asked if the A’s had discussed not playing. He said they did, but it was “too close before game time” to make that decision. He gave individual players the option not to play. Nobody took that option.

I don’t buy the A’s argument that they didn’t have enough time to think about and discuss the decision. The instant the Bucks made their decision, every single person in the A’s organization should have been thinking through the idea about whether they, too, should abstain from playing. They had over two hours from the Bucks decision until Bob Melvin’s pre-game press conference. From the press conference, they still had and hour and a half to discuss it before the game.

Nobody on the A’s except Melvin talked to the media after the game. So at this moment, we don’t know what the A’s reasoning was. We’re left only to guess.

The A’s have three African-American players on the team, including the two highest-paid players on the roster, Khris Davis and Marcus Semien. The third African-American, Tony Kemp, has perhaps been the most vocal of all the A’s players on social justice issues this season. The A’s don’t lack for African-American leadership in the clubhouse on these kinds of issues.

So I’m sure the A’s have some actual reasoning to their decision besides “we ran out of time”. I’m sure we’ll hear it at some point. But this was a very significant day in the history of sports in this country. The A’s had an opportunity to participate in the protest, or to at least give their reasoning why they did not. Instead, all we got from them was a weak justification and an empty argument. It’s disappointing.

The A’s finished the first half of this abbreviated season by losing to the Texas Rangers, 3-2. It was a loss like a lot of the other A’s losses this season: the opposing team throws all their best pitchers at them, and somehow, the A’s still get within a whisker of winning the game anyway. That’s the sign of a good baseball team: you have a chance to win nearly every game. That doesn’t mean you win all those games, sometimes you’re more unlucky than lucky, but you’re fighting each game to the end.

You could change any one of about four different pitches in this game, and the A’s would have won the game. Jesús Luzardo gave up three runs in the first two innings, but he really didn’t throw any bad pitches at all. The first five hits he gave up were all either right on the black of the strike zone, or outside the zone. Somehow, the Rangers made contact on those pitches and found holes. And the home run he allowed was to a right-handed hitter who hadn’t homered at all up to that point this season, who hit a home run to the opposite field. Can’t say that was a terrible pitch, either. Sometimes you do everything right, and the sport of baseball itself beats you.

The A’s got a couple of runs early off Lance Lynn, who has been one of baseball’s best pitchers this season, but then didn’t threaten again until the ninth inning. They loaded the bases with one out for Matt Olson, who was obviously looking for a pitch up in the zone to hit for a sac fly, trying to avoid hitting a grounder for a double play, when the umpire called to pitches *clearly* below the zone for strikes. Olson may not have gotten the job done without those bad calls in that critical situation–he’s been swinging straight through a lot of fastballs lately and is hitting below .200–but again the game of baseball beats you sometimes, as you can’t control what the umpire is going to do to you at any given time, even if it’s the most critical point in the game.

It was a loss, but the A’s finished the first half of the season with a 20-10 record, tied for the best record in the American League. In a year when eight teams from each league will make the playoffs, the A’s would probably have to have a catastrophically bad second half in order to not make the playoffs this year. But anything can happen in just thirty games. Nothing is written in stone.

Half the baseball season is only half the picture, though. It’s half a baseball season in a world turned upside down. We started off with a pandemic and racial unrest, and a major election coming in November, and now we’ve added a climate-crisis fueled wildfire and air quality problem, and Thursday there’s a hurricane about to slam into Texas and Louisiana, and yesterday, police shot another unarmed Black man, this time in Kenosha, Wisconsin.

I had my doubts about whether baseball should even be doing this, and whether they could pull it off. They made some major mistakes early on, with the Marlins and the Cardinals letting semi-epidemics run through their teams, but those mistakes seem to have chastened the rest of the league, as subsequent mistakes, such as some people with the Reds and the Mets testing positive, and with some Indians players breaking protocol, were dealt with swiftly and resolutely, to prevent the disease from spreading any further than that.

I was on the fence about all that before the air quality problems. Now, by contrast, I am feeling very grateful that they are playing. Being stuck at home because of the virus was one thing, but at least I could go in the backyard, or go out for a bike ride if I got tired of being in the house. But when the air outside turned bad, and there was no choice at all but to stay inside the house all day long, I really started getting stir crazy. Those three hours of escapism every day has been psychologically invigorating.

This is only the half of it, though. Who knows what rough beast will be born in the second half, that will knock us off our feet again? We live now, dreaming of victories and triumphs, of glory and greatness, but the shadows of scavenger birds circle us. These thirty games have given us hope, but perhaps they are nothing but the mere pedestal of an ambitious statue that falls over in the desert, eroding away from the wind-blown sands of cruel history.

I had a conversation today with a neighbor’s mother, who had come here after fleeing her home that was near one of the major fires going on in California right now. From her house, she could see the flames on the next hill over from hers. She left not because she thought that she was in immediate danger, as the fire would have to work its way down that hill and back up and over hers, but that she knew she would not be able to sleep because of the uncertainty.

And I got to thinking that this is a pretty good metaphor everything that is going on in this country right now. Maybe we’re not the ones with our house burning down in wildfires, and maybe we’re not the ones who are sick with COVID-19, and maybe we’re not the ones who have lost our jobs in the pandemic, and maybe we’re not the ones who are being subject to police violence, and maybe we’re not the ones who are being rounded up and locked up for deportation, and maybe we’re not the ones suffering from any number of other indignities of American society in 2020, but any of those things and all of those things feel like they’re just one hill away from us, and could potentially strike us at any time. So how do we sleep at night?

When the A’s started their game with the Angels at 1pm, the Air Quality Index near the Coliseum read at 238, which is considered in the “Very Unhealthy” range.

Last year, when our wildfire problem first started, I played an “indoor” soccer game with the AQI at about 120. I put “indoor” in quotation marks because it was in an old airplane hangar under a roof, half the walls are just giant sliding doors, and so the building isn’t exactly sealed airtight from the elements. Just from that one game, I developed a cough that wouldn’t leave me until the rains came a couple weeks later and cleared out the smoke.

From my experience, I can’t fathom why anyone would play a baseball game when the AQI is almost twice as bad as the air I played in. But I guess not everybody has had my experience.

Some people need to make their own mistakes before they adjust their behavior. Some people take the risk and get lucky that nothing bad happened, and think they were right for taking the risk. But that’s not how risk works in the aggregate. And if there’s any team that should understand how risk works in the aggregate, it’s the Oakland A’s.

I’m baffled and embarrassed that they played that game at 1pm. I thought they should have waited a few hours. The pattern has been the last few days that the bad air peaks around 1pm, and then starts getting better around 4pm. That turned out to be the case again for this game. The AQI at 4pm ended up being 123.

When there’s danger lurking on the next hill over, you don’t march towards the hill. You get out of there, to somewhere you can live to play another day, to somewhere you can sleep at night.

The A’s and the Angels paid no attention to my admonishments on Twitter before the game, and played the game. The A’s won 5-4 in extra innings. It was one of the few games the A’s have won this year without hitting a home run. Instead, they did something they have rarely done all year: get some timely hits with runners in scoring position, and then, to win the game, hit a sacrifice fly with a runner on third and less than two outs. It would have been a fun game to talk about, if I wasn’t so outraged that they were playing it at all.

No word afterwards if anybody developed any respiratory problems from playing in the bad air.

Good defense is a characteristic of this generation of the Oakland A’s. I’ve gotten so used to it now that when the A’s don’t make a defensive play, even if it’s a difficult one, I’m surprised.

Therefore, I hereby note that in the 28th game of the 2020 MLB season, the Oakland Athletics flubbed at least half a dozen plays on defense that they would ordinarily make. Two of these flubs, both my Matt Chapman, ordinarily the best defensive baseball player on the planet, led to all four runs that scored against them in this game, which the A’s ended up losing, 4-3.

The A’s officially committed three errors in the game, by Matt Chapman, Tony Kemp, and Marcus Semien. There were also a few plays not made which were not errors, but could have turned into outs, but didn’t. The first run of the game scored on a play ruled a fielder’s choice. It was a grounder to third with a runner on third and one out. Matt Chapman fielded a grounder by Mike Trout, and threw home to get the runner who went on contact. A good throw would have the runner out, but Chapman’s throw short-hopped the catcher, Austin Allen, and the time it took for Allen to gather the ball let the runner slide under the tag.

In the second inning, with runners on first and third and one out, a ground ball came to Matt Chapman, who could have turned a double play, but instead flubbed the ball for an error, and everybody was safe. The inning could have been over right there, with no runs scored. Instead, a run was in, and two batters later, Mike Trout doubled in another pair of runs.

So Matt Chapman could have made two plays, but didn’t, and the Angels led 4-0 instead of it being tied 0-0.

The A’s, being the good team they are, fought back, and got within a run, but couldn’t get all the way back to tie the game up.

Does the A’s defense suck because it sucked in this game? It’s only one game out of sixty. One bad game does not make a trend.

That’s easier to remember in baseball, when the next game is tomorrow. It’s easier to hold onto the idea that the A’s have, if not the best, but one of the best defenses in the world.

In a game like politics, however, when the next game is two, four, or six years later, a bad game, a bad administration, an imcompetent regime, it can be difficult to believe that what’s going on now isn’t a permanent change. The American government sucks right now, it can’t do anything right, and it’s easy to lose confidence in our system when that happens. But if America elects a competent government in November, perhaps this bad regime, this bad year, can be forgotten as an anomaly, a bad period in the long history of a great country, like a bad defensive day by a great defensive team in a long baseball season.

A 5-3 score is perhaps the most ordinary outcome for a baseball game. It is not the most common outcome, mark you. I’m going to differentiate here between common and ordinary. 5-3 is an ordinary score because it’s not the most common of anything. It is the seventh-most common final score in MLB history. The two-run difference between winner and loser is not the most common difference. A one-run difference is, of course. 5-3 is not the most common two-run difference, it’s second to 4-2. So 5-3 is the second-most common outcome of the second-most common run differential.

In other words, this A’s 5-3 victory over the Angels was in many ways quite ordinary.

I’ll take ordinary. We have a dysfunctional federal government in a pandemic in a climate crisis that is leaving our state on fire and the air unhealthy to breathe, and we’re all stuck in our homes with the schools closed and the kids trying to do a school year online which we’ve never tried to do before, and God, I really could drink in a nice, big, cold glass of ordinary right now.

Neither starting pitcher in this game, Mike Fiers or Andrew Heaney, was great. Nor were they horrible. They were ordinary. The A’s, for once, got a two-out hit with runners on, when Stephen Piscotty doubled in two runs in the top of the first, that put the A’s ahead 3-0. There were not any dramatic turns after that. The A’s, for once, got a two-out hit with runners on, when Stephen Piscotty doubled in two runs in the top of the first, that put the A’s ahead 3-0. There were not any dramatic turns after that. The win probability chart was as close as a straight line from 50 in the first inning to 100 in the ninth as a baseball game can get. It was a straightforward game, from start to finish.

If there was anything remarkable about this game, is was more in what the Angels did than the A’s. Anthony Rendon went 4-for-5, and seems harder to get out right now that Mike Trout, if that’s even possible. David Fletcher had three hits, one of which was on one of the worst pitches I’ve ever seen anybody get a hit on. It was literally a fastball on the inner half of the plate above his eyes, and somehow he put his bat on it for a double to right field.

Those types of hitters, who can hit any pitch you throw in any location, good or bad, I find extremely annoying to face as an opponent.

The top of the Angels lineup is might be the best lineup in the AL West. It’s a series of incredibly tough outs. But there are holes in the bottom of their lineup, especially with Pujols and Ohtani not playing up to their previous standards. With ordinary pitching, they’d probably be an above-.500 team. But their pitching has been bad. Too many holes, and so the Angels are 8-19, while the A’s are 19-8.

Hey, so remember six days ago when we had a brownout so I went out to my car and cranked up the radio and listened to the A’s game? Well, maybe that wasn’t my greatest idea, because I didn’t drive my car at all after that for five days because, you know, you’re supposed to stay home because of all the pandemics and bad air quality and stuff, and so when my wife went to start the car yesterday to go run an errand, the car battery was almost completely out of juice, and it wouldn’t start.

I have a car battery recharger thingy that I’ve had in my garage since, well, I don’t know, I can’t remember where I even got it from. I’d guess I inherited it from my dad, who passed away 23 years ago. This was the first time I’d ever used it. I took it out of its faded and warped cardboard box, and the dang thing was pristine, not a scratch or a dent or a smudge on it. For all I know, it may be the first time it had ever been taken out of that box.

I read the instructions and connected it up to the car battery, and let it start recharging the car battery. I thought it would take an hour or three to finish, but it was more like six or seven hours, and by the time the indicator light went on saying that it was done, it was almost midnight. I disconnected the charger, started the car to make sure it worked, then closed up shop and went to bed.

So this morning, I had some errands to run, but I didn’t really trust my car battery to work, and I didn’t want to get stuck in some parking lot somewhere needing help to jump my car, when the air quality was unhealthy and a pandemic is going on, so I started up my car and drove it to my in-laws’ house, parked my car there, borrowed their car to run my errands, and then went back and swapped cars again, and drove our car back home.

None of which is of any particular consequence in the big scheme of things, except for noting that all the little minor inconveniences that we have to deal with on a normal day in a normal year in a normal life, feel so much more bizarre and surreal in a bizarre and surreal year.

A’s first base coach Mike Aldrete missed today’s A’s game because his home is apparently near one of the ten gazillion wildfires burning in the state of California at this time, and he needed to be home to handle that problem.

The rest of the A’s weren’t immune from that problem either, as when the game started, the air quality around the Coliseum was registering in the 100-150 AQI range, which is designated as “Unhealthy for Sensitive Groups”. By the end of the game, it had climbed over 150 into the “Unhealthy” range. If you ask me, I think they should have postponed the game at that point, like you would in a rainout. But I kind of don’t think the idea even crossed their minds, as even though they keep saying bullshit like “the health of our employees is our top priority”, it clearly isn’t because this being the last game in the season between these two teams, nobody wanted to have to deal with the logistics of how to finish this game on another date. So maybe they should be honest and say, “Logistics is our top priority, but the health of our employees is probably somewhere in our top ten list of priorities, and almost certainly in our top twenty.”

Putting aside whether they should be playing at all, (a major theme running through the season) this was a very enjoyable episode of A’s baseball. In this 5-1 victory over Arizona, Matt Chapman hit two monster homers to the second deck in left field, and Matt Olson hit a home run, as well. And perhaps most importantly, Khris Davis hit the ball hard three times, once to left, once to center, and once to right. All season up until now it has seemed that Davis has been trying to pull every pitch for a home run, but in the last two games he has played, he has shown signs of coming out of that, of hitting the ball hard in the direction the pitch lets him hit it. If he can keep doing that, and he can get back to the great hitter he was from 2015 to 2018, the A’s offense might become a juggernaut.

And then there’s Sean Manaea. He lasted 5 1/3 innings, but honestly, I don’t know how he did it. He only had good velocity in the first inning. After that, his fastball was mostly 88-89mph, and so far this year, as soon as his fastball has dropped below 90mph, usually around the 4th inning, he’s started getting hit hard. But this time, it dropped below 90mph in the second inning, and he kept getting outs. I suppose it helped a lot that he was able to locate his offspeed pitches well.

Manaea is starting to remind me a lot of Barry Zito. When Zito first came up, his fastball was in the 90s, and his curveball and changeup were so good as well that whether or not he was locating his pitches, he could get batters out. But then the fastball began to lose velocity, falling into the upper 80s, and Zito became more inconsistent. On the days when is command wasn’t right, or one of his pitches wasn’t working, he became much more hittable. Instead of a dominant pitcher who could win a Cy Young, he turned into more of a .500 pitcher, who could dominate on his good days, but also struggle mightily on his bad days, and it all added up to something mediocre.

This was a good day for Manaea, but I am still not confident that today’s Manaea is the new, real Manaea. I think that unless that Manaea can somehow get that velocity back for good, the real Manaea is this mediocre Manaea who has his good days and his bad days, depending on his command, and you’re never sure which one you’re going to get from start to start.

It’s a short season. Do the A’s have the time and patience to figure out what they have in Manaea? The trade deadline is in 10 days. Manaea should get two more starts before then. Two more pieces of data left from which to make a decision about him.

Still, the A’s are 18-8 now, and have the best record in baseball. If your biggest worry is that your fifth starter is kind of mediocre, you don’t really have the kind of major problems everyone else is having, you just have some minor inconveniences.

Ever know of a story that would fit the moment, but it’s not your story to tell? Can you avoid the temptation to tell it anyway?

There are two problems with stories that belong to someone else:

I was watching the A’s-Diamondbacks game (a fun 4-1 A’s victory led by Jesús Luzardo’s best start thus far) when word came over the Twitter wire about a homophobic slur uttered on the air by Reds broadcaster Thom Brennaman.

I could tell some stories here which related to that, but I’m not going to, because of the reasons in the first section above, and also because that essay would pretty much have the exact same structure, and come to the exact same conclusion, as my essay two weeks ago about Ryan Christenson.

The conclusion is this: what people really want when some famous person does something appalling is not for any particular specific punishment. People don’t really care if these offenders are fined some money, or lose their job, or go to jail. What people want in these situations is for that person to lose their status.

You could fine a famous person a huge chunk of money, AND take away their job, AND send them to jail, AND make sure they give a sincere, heartfelt apology, AND make amends for all the damage their bad behavior caused, but if after all that they come back and end up with the same status they had before, nobody is going to be satisfied.

What we really want from people like that is for them to have to start over, from the bottom. Being famous has huge outsized advantages in our high-tech media culture. Take those advantages away. Humble them. They did something stupid, like a young ignorant fool. Treat them like that young person, who doesn’t know what they’re doing. Start them at the bottom, and make them have to earn their way back up.

That’s not too hard to do when it’s a coach, or an announcer. Send them down to the minorest of minor leagues, and move everybody up a notch.

That’s harder to do for a player. You’re not allowed to send a 10-year veteran to the minor leagues, for example, your only choice by the rules is to let them go. But for younger players, the rules allow for that. The Cleveland Indians did exactly that recently with Zach Plesac and Mike Clevinger, who violated the COVID-19 protocols and then lied about it. Because both of them had options remaining, the Indians sent both of them down to their alternate site, and are kind of letting them rot there. It may be costing Cleveland some victories, because both of them are good players, but they felt it necessary for everyone to be satisfied.

So the point is, again, just like the Ryan Christenson incident: despite most of the rhetoric you will hear, these reactions are not really about seeking punishment, or about surpressing free speech. It’s about lowering status. Thom Brennaman said something horribly homophobic, and people will not be satisfied until Thom Brennaman’s status is lowered, not as the first act in a redemption play, not as the first scene of a death and resurrection story, not even as the origin story of a true villain, but until he is just as anonymous as the rest of us, the non-famous, the forgettable and forgotten, whose stories will never be known by anybody.

As I’m writing this, word has come down that there is a wildfire in the Santa Cruz Mountains. People near the fire are being asked to evacuate. Smoke from the fire is descending into Silicon Valley and making the air quality bad. The bad air hasn’t reached me in the East Bay yet, but I imagine it’s only a matter of time.

I don’t know how I’m going to muster the energy to deal with all this stuff all at once. And I’m not even, you know, actually doing anything. I’m not an essential worker. I’m not a firefighter. I’m basically just an ordinary citizen, hiding away at home, trying not to make things worse for anybody else. But it’s like a literal siege. We’re trapped inside the walls of our house, and everything on the outside of those walls is hostile and wants to kill us.

For some people, who live in dangerous parts of the world, every day of their life is like that. Not that I didn’t understand that intellectually before, but on an emotional level, I’ve lived a fortunate life. I’ve had bad days, and bad situations, but they’ve always been temporary, and I’ve never thought of them as anything other than temporary. I’ve never before experienced the exhaustion of life being one bad thing after another, constantly, with no end in sight. Even with the pandemic, I’ve sort of been able to hang on to the optimistic idea that it is temporary, that we will get over this at some point. But this fire thing, the air quality thing, again, it’s pushing me to the edge. I don’t know how much longer I can cling to these cliffs of optimism. I can feel myself letting go, contemplating the idea of letting the despair swallow me.

There’s really only one thought that’s keeping me hanging on, that makes me determined to hang on to my optimism, to not give in to despair and cynicism: the idea that becoming too exhausted to fight back is exactly what the damn fascists want, because their opponents giving up is the only way, in the end, they can win, and I will not let that motherfucker Donald Trump beat me.

I don’t care how much bullshit is thrown at me, I don’t care how many battles I lose, I don’t care how beaten down I feel, they only way they win in the end is if we give up, and I will not let that asshole win.

Speaking of being beaten down, the A’s lost to the Diamondbacks 10-1. Frankie Montas was coming back from his back strain, and although he claimed he felt good physically, for whatever the reason, he couldn’t locate any of his pitches, and he got pounded: 1 2/3 innings pitched, 9 runs allowed.

It just wasn’t his day, or the A’s day. Some days, you just get your butt kicked. It happens. Don’t give up, come back tomorrow and try again.

That is, if you’re allowed to even play tomorrow. There may be a big giant fire blowing smoke into the Oakland Coliseum making the air quality too harsh to play in. You never know. It’s been that kind of year. But you can either let it beat you down so you give up and quit, or you can choose to deal with it the best you can, and keep going until you win.

It’s a weird thing, but in this version of Catfish Stew I seem to have a hard time getting started writing these essays until I come up with a title. Once I have a title, it all flows from there. But if I don’t have a title, the words get stuck. I don’t know where to start, I don’t know where to go.

I don’t always stick with the title I start with. Sometimes I think I’m going to build the story around one metaphor, but then I discover a different one along the way that works better, and I change it.

The titles come from wherever a creative idea comes from: the subconscious output of the System 1 mind, taking in the disparate elements that I am trying to tie together– the game, the news of the day, what’s going on in my life, plus and perhaps most importantly, the emotions I’m feeling as a result of all of this.

So after a game, I kind of go around and let all this stuff stew together. Maybe I do the dishes, or go for a bike ride, or have a snack, and at some point while I’m doing this other thing that is not writing, my subconscious will assemble this data, find some pattern that connects these things, and a title will pop into my consciousness.

So today, I’m thinking about A’s losing the exact kind of game that they’ve been winning lately, and also the “scandal” of Fernando Tatis Jr. hitting a grand slam on a 3-0 pitch with a seven run lead, all while the Democratic National Convention was getting started. Somehow, the phrase “Don’t get cocky, kid” pops in my head, and I think, “Ooh, that could work, let’s go with that.”

That phrase is from Star Wars, the Original Film, or so I thought, until I googled it and found out that the real phrase that Harrison Ford actually uttered in the film is, “Great, kid! Don’t get cocky.” Which, IMO, doesn’t actually work as well as a title as the phrase that popped in my head. So the inaccuracy stands.

The phrase is, of course, a warning: that even though you may have had some success, that doesn’t mean you’ll have success the next time, or that any of this is going to be easy.

And that warning is why some old-school baseball types were mad at Tatis swinging on that 3-0 pitch. Of course, in that situation, you’re going to get an easy pitch to hit. Don’t think you’re hot stuff just because you hit an easy pitch.

But the phrase is also a warning in the other direction: just because you’ve had success in this game so far with a seven-run lead, don’t think the rest of the game is going to be that easy. I mean, did any of those people even pay the slightest attention to the A’s-Giants series this weekend? The A’s scored five runs in the ninth on Friday, four runs in the ninth on Saturday, and then had a nine-run fifth inning on Sunday. The A’s trailed in all of those games, but never, ever gave up, fought to the very end, and came back to win all three.

So why should Tatis and the Padres assume the game is locked up? What is wrong with the Rangers that they assumed they’ve already lost?

The A’s, by the way, fell behind 3-0 to the Diamondbacks yesterday. They were no-hit for five innings by Zac Gallen, who was absolutely brilliant. I’d never seen the guy pitch before, but I have to assume from this performance that he is an up-and-coming star. His changeup was simply amazing all day long, dancing along the bottom of the strike zone, sometimes just barely in the zone, sometimes dipping below it, keeping the A’s hitters mesmerized all evening long. Robbie Grossman managed to connect with one of his pitches for a solo homer, but other than that, the A’s did nothing against him.

But did the A’s give up? No, dammit! They fought to the very end. And when Gallen hit his pitch limit and the Diamondbacks bullpen took over, the A’s got to work. They immediately tied the game 3-3 thanks in part to a costly error by Nick Ahmed.

At one point during the game, Michelle Obama was giving her convention speech, so I switched the channel from the game to watch it. Her basic message was this: yes, our opponent sucks, yes, we have a big lead in the polls, but baseball is baseball, and politics is politics, and you can’t assume that your opponent will give up so you can’t assume any lead is safe. You have to do the hard work, every day, every play, to make sure you win that game.

In this game, however, it didn’t work out for the A’s. Arizona scratched out a run in the bottom of the ninth to beat the A’s 4-3. But even though the A’s lost, the fact that they came back to tie the game even against probably the best pitching performance against them all year, is a warning to the rest of baseball: never get cocky about any lead you have against the 2020 Oakland A’s.

The baseball gods tried their best to make me miss yet another ballgame. But little did they know that yesterday I decided to change religions, so I thwarted their thwarts.

I was awakened this morning around 4am to a thunderstorm. I was completely unaware beforehand that a thunderstorm might be coming, so I had a whole bunch of windows open to thwart the heat, which had reached almost 100F the previous day, and was projected to get over 90F again. So as the rain came down, I had to get out of bed to close those windows to keep things from getting wet.

That thunderstorm kept me awake for a couple of hours until it passed, and then I went back to bed. I woke back up around 10:30am, which is probably the latest I’ve awakened in years. Game time was 1pm for the A’s-Giants game was 1pm, so I checked the weather forecast to see if there were any more surprised in store. The report did not give any indication that the game would be in any danger of not being played.

And then just around noon, seemingly out of nowhere, there came a thunderclap that was as loud as any natural sound I had ever heard.

If the lightning bolt had hit my house, I would not have been surprised. It’s been that kind of year. But it did not. Instead, the lightning hit a nearby power station, and blew out three transformers. Power to a large chunk of Alameda was immediately cut.

But for once, my house was spared the power outage. So let the game commence!

The game started out like a lot of A’s games this season: the A’s kind of plodding along against the opposing starter, and the A’s starter (Mike Fiers this time) kind of plodding along, too, keeping the game close until the bullpens come into play.

The score was 2-2 when Giants starter Logan Webb ran out of gas, and was replaced by left-handed reliever Wandy Peralta. And as we’ve seen before this season, this was another example of the three-batter minimum playing to the A’s advantage. Giants manager Gabe Kapler saw Matt Olson sitting as the third batter that the reliever would have to face, and if he wanted a lefty to face Olson, he would also have to face the two batters before him. This allowed the A’s to pinch hit right-handed batter Chad Pinder for left-handed batter Tony Kemp. Pinder has some of the biggest platoon splits on the A’s, he’s never hit righties well at all, but he’s pretty good against lefties.

And that’s when the metaphorical thunder started.

Pinder crushed Peralta’s first pitch, a 94.7mph fastball right down the middle, sending it the other way at 112.1mph and 422 feet away into the left-field bleachers. That gave the A’s a 4-2 lead.

Peralta ended up failing to retire a single batter. Matt Chapman and Matt Olson singled (Olson’s being a perfectly laid bunt against a shift), Mark Canha tripled to drive them in, making it 6-2. When Robbie Grossman followed with a walk, Kapler replaced Peralta with Dereck Rodriguez.

On the sixth pitch to Piscotty, Rodriguez hung a curveball to Piscotty. Piscotty obliterated the pitch, sending it 32 feet farther than Pinder’s blast, landing at the top of the bleachers and then rolling under the giant baseball glove behind the bleachers.

A few batters later, when Marcus Semien also homered on a hanging curve from Rodriguez (this one traveling a meager 379 feet), the A’s had scored nine runs in the inning.

The rest of the game was just a mere formality, save for the major league debut of A’s pitcher James Kaprelian, who pitched a solid two innings, giving up one run. Final score: A’s 15, Giants 3.

The A’s have the best record in baseball now at 16-6, which is fun. The complete dominance in this game aside, I don’t know that the A’s are quite as good as their record. But they are good.

You can see from all the mistakes the Giants made in this series that their team is full of holes, and the A’s team isn’t. The A’s are solid everywhere, and so while they can be beaten by other teams when they play well, if the other team does not play well, the A’s will often at a minimum just grind through and outlast the opponent, and if the other team plays flat out poorly, like today, the A’s have enough lightning on their roster to strike them down and blow them out.

…were the exact words that came out of my mouth the moment Mark Canha hit his three-run homer in the ninth inning.

For the second game in a row, the A’s hit two home runs in the ninth inning off Giants closer (for now) Trevor Gott.

In the first game, the A’s overcame a 5-run deficit in the ninth. Matt Olson hit a leadoff homer, and Stephen Piscotty hit a game-tying grand slam. The A’s eventually won that game 8-7 in the 10th inning.

In the second game, the A’s overcame a 3-run deficit. Sean Murphy hit a leadoff homer, and Canha hit a 3-run homer to give the A’s a 7-6 lead, which they held onto for the victory.

The A’s became only the fourth team in MLB history to overcome 3+ run deficits in the ninth inning or later in back-to-back games.

I am of three minds about this stunning turn of events:

Pure joy is not a thing that exists right now, at least not for long, at least not for me. Happiness is ephemeral. You try to grab it when you see it, but then when you open your hands to look at what you’ve caught–poof, it’s gone.

That’s a remarkably Lutheran thing to say, now that I think about it. It’s like living in an Ingmar Bergman film, with a Lutheran priest hanging over your head, ready to remind you how difficult life is, to impose upon you the discipline needed to overcome those difficulties, with the side effect of also stomping out any little joy you may muster up.

Maybe I need to find a different religion.

I…*sigh*.

There’s an old political joke that goes: Republicans believe that governments lack competence, and so when they hold government power, they set out to prove their theory.

Which…I don’t know. Like any joke, it is both appropriate and inappropriate at the same time. It just seems to me like imcompetence is spreading like a virus throughout our society. And like a virus which doesn’t care if it infects a Democrat or a Republican, imcompetence doesn’t care if it infects the government or the private sector, it just keeps growing no matter what.

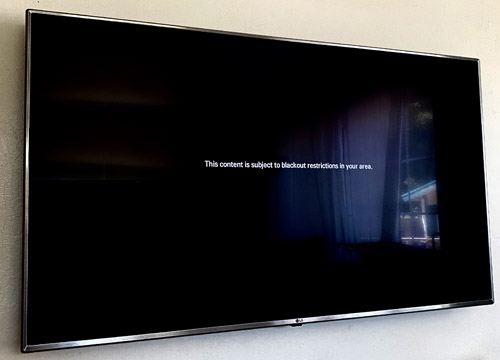

Take, for example, the last two A’s games I have tried to watch. On Wednesday, when I tried to turn on the A’s-Angels game on my TV, I was greeted with this message, indicating that the game was blacked out in my area:

This should not have been the case. What seems to have happened was this: the game was being broadcast locally on the NBC Sports California channel, and also nationally on the MLB Network channel. If you’re in the local area, the MLB Network content was supposed to be blacked out, in order to force you to watch on NBC Sports California. However, my service provider, Sling, blocked out NBC Sports California, instead.

So I got online, and I complained: to Sling, to the A’s, and to A’s President Dave Kaval. Kaval acknowledged the mistake, and said he’d try to fix it. Sling messaged me, acknowledged the mistake, and said they’d try to fix it.

I appreciate the acknowledgements. But it did not get fixed.

This is not the first time this has happened, so I remembered a workaround from the last time: I could log into the NBC Sports app using my Sling credentials, and watch the game on my computer instead. Which was OK for a workaround, but that’s exactly what it was: a workaround.

There was nothing governmental about this imcompetence. This was 100% the fault of private sector, which, in the aim of maximizing profits, created byzantine, complicated rules about who can see what content and where and on which technologies, rules which are too hard to follow on a consistent basis without making mistakes.

For the following game (A’s vs Giants), I was not blacked out from watching it. Instead, I was browned out.

It was a hot day in Northern California, which apparently taxed the state electrical grid enough that the state electrical regulators decided they needed to start implementing rolling blackouts. Which they did, at exactly 7:30pm, 45 minutes into the game.

So for the second game in a row, my consumption of A’s baseball was interrupted. My power was out, so my TV wouldn’t work, nor would my internet connection. I tried to use cellular data, but the signal was very weak. No way I could stream anything. I could get some Twitter updates, that was about it for data options. Which left radio as my only possible workaround. Until a couple weeks ago, even that might not have worked, because the A’s had gone streaming-only. But they had recently picked up a Bay Area terrestrial radio station, AM 960, to broadcast their games. However, the only transistor radio I own only gets FM radio now; the AM on it has broken for some reason. So I had exactly one option: my car radio.

So I went outside to the car in my driveway, opened the windows, turned up the volume, and sat out on my front porch to listen to the game in the warm evening.

Which actually turned out to be a quite pleasant experience. Some neighbors who also had lost their power decided it was good time to take a walk. I chatted with them as they walked by on the sidewalk. Again, it was not what I had planned, but the workaround was tolerable.

But what has happened? Brownouts used to be a thing that only happened in developing countries. But ever since our electrical grid was deregulated in 1990s, brownouts have become a regular thing in California. How did we become so imcompetent? Democrats will argue that deregulating the grid and privatizing PG&E was all a big mistake, while Republicans will argue that it was only a partial deregulation, and they should have gone all the way.

This argument repeats itself in other areas besides electricity: healthcare, education, the prison system, etc. And now the Trump administration is now trying to “fix” the post office, and in doing so, are rendering imcompetent both the post office itself, and all the systems that depend on it: small businesses, medicinal delivery, and elections. You can choose sides picking out the blame, but whether socialized or privatized, it seems to me imcompetence happens no matter what you do. The DMV is socialized, but nobody looks at it as a bastion of competence. Cable TV is privatized, but trying to get any service from them is as frustrating as the DMV.

There’s something else going on here that neither the Democrats nor the Republicans are modeling correctly. I think it has to do a phenomenon I explained in an essay I wrote in 2016 called The Data/Human Goal Gap.

To summarize: a good way to improve any human endeavor is to measure your success. Try something, measure what you did, keep the stuff that the measurement says works, throw out the stuff that the measurement says doesn’t work, and then rinse, lather, and repeat.

Doing this puts you on a trajectory of change, which almost always brings you closer to the success you are trying to achieve, at least at first. And because this trajectory worked in the past, you come to believe in those measurements you took, that these measurements are the key to success.

The problem comes when the thing you are measuring is not exactly the actual goal you are trying to achieve. When there is a gap between your goal and your measurement, the measurement can only take you so close to your target. Once you reach that closest distance to your target, if you keep following that same trajectory, you will start to move further away from your target instead of closer to it.

Politicians measure themselves with polls, and with election victories. But poll numbers and election victories are not the end goal of politics. The end goal of politics is the welfare of the people. Measuring yourself with election victories, when you come from a dictatorship, can start to yield improvements in welfare over time. But at some point, the things that bring you election victories can cease to be the same as the things that improve the welfare of the people. When that happens, the only way to improve the welfare of the people is to be willing to do things that will lose you an election.

But because the name of the game is winning elections, and politicians believe in that particular game, and we have reached a point where public welfare and election numbers have diverged, politicians can’t bring themselves to do the things that will increase our welfare, because they can’t let themselves go from the measurements they cling to. And the people start to regard politicians as being ever more imcompetent at their jobs.

Similarly, a profit motive might help you build an electrical grid effectively at first. But after you reach the minimal possible distance between your target (profit) and your goal (a reliable electrical grid), chasing further problems takes you further from your goal, not closer, as we saw with the California electricity crisis of the early 2000s. Profit motive works great until you reach that critical point where it becomes counterproductive. That’s when you need to shift gears, change directions, and measure yourself by something different that will get you back to moving towards your goals.

If I’m right, if this is what’s going on, the left and right dichotomy in our politics isn’t helpful. The profit motive isn’t always bad, as diehard socialists say, or always good, as diehard capitalists say. It’s sometimes good and sometimes bad, and it requires wisdom and intellectual flexibility our politicians and political parties lack in order to tell the difference.

So: two straight days of infrastructural imcompetence while trying to watch the A’s. Doubly frustrating: two straight games of imcompetence on the field, too. The A’s were getting their butts kicked by the Giants while I was listening to the radio, utterly unable to hit Giants starting pitcher Johnny Cueto (who is incidentally one of my favorite non-A’s pitchers). But I was kind of enjoying the evening in the warm but pleasant air of a summer evening, so I didn’t hurry back to my TV when the power went back on about an hour later. I just kept listening to the game on the radio.

When Cueto left the game, the A’s started to chip away at the Giants lead off Cueto’s less competent successors. The A’s entered the ninth inning trailing 7-2.

The A’s got a home run from Matt Olson to lead off the ninth to cut the lead to four runs. After by a mental error by Giants first baseman Wilmer Flores, whose indecision turned a potential double play into no outs, the A’s loaded the bases for Stephen Piscotty.

As A’s radio announcer Ken Korach called Piscotty’s grand slam which tied the game at 7-7, I leaped out of the chair I was sitting in and rushed back to my TV to see it instead of just hear it. I ended up watching the rest of the game on TV, no more blackouts, no more brownouts, and the A’s ended up winning the game in 10 innings, 8-7.

It was a remarkable comeback. A’s manager Bob Melvin said the victory had a “high degree of difficulty”. But there may be a lesson to learn there. Everything may seem hopeless and riddled with imcompetence one minute, but if you don’t give up, if you are willing to change your perspective and adjust your approach, you can sometimes discover a new path to success that you didn’t even know was there.

Yesterday, in my Freudian slumber, I dreamed myself the wisdom of a pelican, soaring over land and sea, over rooftops and houses, taking in the aerial views of the ground, where with my wide perspective on every thing below me, nothing could hurt me at all.

I wrote how Ramón Laureano and Kamala Harris are now entangled in my own dreams, connected by a random juxtaposition of fates. Further, I wrote an imaginary scenario where I’m imagined Harris 16 years from now having been very successful, and implying by omission that Laureano would be retired by then and maybe almost forgotten.

<Ramón Laureano charges Ken Arneson and starts a brawl>

Although I never referenced Ramón’s retirement, my actions were inappropriate. I apologize for my part in yesterday’s unfortunate incident. As writers, we are held to a higher standard and should be an example to the others. Hopefully, other writers will learn from my mistake so that this never happens again in the future.

In a dream, nothing is quite what it seems. I had no reason to assume that 16 years from now, Harris would be remembered and Laureano would be forgotten, when it quite easily could be the other way around. I realize now that my dream was empty and absurd.

Laureano has been sentenced to drift into suspension for six games and as an A’s fan, you hope, because it’s only a week, that the A’s can get by without Ramón Laureano for that period and be fine, and we won’t miss him too much.

We will miss Ramón Laureano. Laureano made sure, in today’s game, likely his last before the suspension, to make clear exactly how much.

In his last at-bat of the game, Laureano singled in two runs, to seal an 8-4 victory for the A’s. But it wasn’t his bat alone that will make us remember him.

Perhaps playing with added incentive in this game, Laureano covered that green center field like a vacuum cleaner possessed, determined to not to allow any ball to fall for a hit. He made one diving catch in front of him, one leaping catch just in front of the wall, and then, perhaps most remarkably, leaped over the fence to take a home run away from the opposing Angels.

Laureano came to America as a teenager, alone, to pursue his baseball dreams. He has had doubters all along the way. All along the way, he has worked his ass off to prove those doubters wrong. He continues to work his ass off, to prove all those doubters wrong. He is focused and determined.

Too focused and determined, perhaps, in a pandemic. That’s why he’s being suspended. But in most eras, focus and determination is a good thing. Focused and determined people may make mistakes, but they will learn and improve from them.

Ramón Laureano regrets charging Alex Cintrón. I regret doubting Ramón Laureano. This game: points made, lessons learned. We made mistakes, but we will build on them and come back better.

In most team sports, the truly elite, best-of-all-time teams win about 90% of their games. The best regular season NFL team of all time won 100% of its games. The best regular season NHL team of all time (counting ties as half a win) won 91% of its games. The best regular season NBA team of all time won 89% of its games. The best English Premier League of all time won 88% of its games.

Baseball is harder. The best regular season MLB team of all time, the 2001 Seattle Mariners, won just under 72% of its games.

Even if you’re the best team in baseball, on some days, the best player in baseball will beat you. Or a starting pitcher who is better than your starting pitcher that day will beat you. And it’s not some occasional random fluke. It will happen about 35-40% of the time. That’s baseball.

I think we sports fans who enjoy multiple sports sometimes forget how different baseball is. If we think our team is good, we carry our other-sport expectations with us, and want them to win about 90% of their games. When they don’t, we feel like they’re not living up to their potential. We feel like they’re letting us down.

The lesson, therefore, is: never watch any other sports. Watch baseball, and only baseball.

That’s a joke, of course. Baseball is my favorite sport to watch, but I never really played it much. As a player, my sports have been basketball (before my back and knees made me quit) and soccer. But with contact sports being out of the question because of the pandemic, I’ve had to resort to my (roughly) 23rd-favorite sporting activity, cycling, to get my exercise.

I get bored of most forms of exercise if I’m not chasing a ball. To give my cycling a goal to chase, I try to ride around and find something new. There’s a lot of construction going on near my house, so if I vary my routes, I can usually find something new that’s happened around town.

Yesterday on my bike ride, I was riding along the bayshore, and I came across three pelicans flying around in circles, looking for food in the bay, and as soon as they found something, quickly diving down to catch it. I filmed a video of one of them.

It was a very peaceful moment. For a few minutes, all the troubles of the human world disappeared. Instead, I was onstage for a performance by a completely different species. There was no anger, no disappointment, no frustration. There was just being, free of judgment.

When I got home from my bike ride, I opened up my Twitter and was instantly given two major pieces of information:

And then my Twitter feed was full of all sorts of opinions and judgments about these two major pieces of information.

These two news stories are completely independent of each other, but now they will always be linked in my mind, both because they arrived in my consciousness simultaneously, and because they were national stories, and even international stories, that both involved Oakland.

Kamala Harris, who was born in Oakland in the same hospital as my wife and two of my kids, could spend the next eight years as Vice President, and the following eight years as President, and every time sixteen years from now I think back about her career, and make some kind of judgment in my mind whether she was a good or bad VP or POTUS, I’m going to think about Ramón Laureano and the time he charged the entire Houston Astros dugout in the Oakland Coliseum in the middle of a pandemic.

That’s just how it is now.

Later that evening, the A’s lost their second straight game, 6-0 to the Angels. Mike Fiers didn’t really have his curveball, which made him much less effective than otherwise. Meanwhile, Dylan Bundy had all his pitches working for the second time against the A’s this season. And with two straight poorly pitched games, panic started setting into my mind. Oh NOeS! WE cAn’T WiN 90% oF OUr gAMeS iF wE LoSe tWo gAmES iN A rOW! WE NeEd NeW PItcHErS! MaKE sOMe tRaDEs!

That isn’t a particularly helpful or useful state of mind for a baseball fan. A baseball fan needs to be more like a pelican, circling around, calmly looking down at these events from a distance, only making a judgment when it’s worth taking a closer look at a particularly delicious-looking fish.

Once upon a time, there was a land called America whose rulers became imcompetent. The amount of imcompetence coming out of the White House and various state governments was staggering. Yes, I said imcompetence, because, well, at first I made a typing mistake, and then I realized that this mistake more accurately described their imcompetence than spelling it correctly, so I decided it should stay, now and for the rest of this essay.

I was thinking about this story because I was reading today an essay by John Cochrane, who said that we wouldn’t be so desperately waiting for a vaccine right now if our testing systems weren’t riddled with imcompetence:

A vaccine is a technological device that, combined with an effective policy and public-health bureaucracy for its distribution, allows us to stop the spread of a virus. But we have such a thing already. Tests are a technological device that, combined with an effective policy and public-health bureaucracy for its distribution, allows us to stop the spread of a virus.

For that public health purpose, tests do not need to be accurate. They need to be cheap, available, and fast. When the history of this virus is written, I suspect that the immense fubar, snafu, complete incompetence of the FDA, CDC, and health authorities in general at understanding and using available tests to stop the virus will be a central theme.

Tsk tsk, Cochrane spelled imcompetence correctly, thereby completely whiffing on matching the theme of this whole essay. What an imcompetent boob.

There used to be a phrase “the strong, silent type”, which was meant as a good thing, meaning a sort of consistently reliabile person for whom competence was its own reward. Technology has changed all that. Television and the Internet have made fame the most valued character trait in our society. You can’t win in our culture by being silent, you have to call attention to yourself. If you’re not on social media, you’ll have no fame, and therefore no value. A person who shuns social media must be instead be some kind of creepy lonely pervert. Nobody admires that. Meanwhile, if you are on social media, every dumb idea that passes through your brain will lay bare your imcompetence for the whole world to see. But it doesn’t matter if you’re imcompetent, because at least you’re famous, which is what really matters.

But hey, maybe I’m just complaining because I’m jealous, because I’m the type of person who lacks the kind of charm and charisma to direct the world’s eyes on my visage, and therefore I have no choice but to pin my self-esteem on my worthless ability to avoid imcompetence. It’s not like I can invent a culture dedicated to cancelling the power of celebrity, and promoting the power of competence, or expect one to organically emerge. That will never happen. People love celebrities! So what’s the point of being competent if nobody notices it?

That’s my flaw, I guess. It’s my bad for being frustrated when we elect leaders who are complete geniuses at staying famous, while the imcompetence piles up, and millions of people suffer needlessly downwind of it.

I watched a baseball game today between the A’s and the Angels, played in Anaheim. It was riddled with all sorts of imcompetence from pitchers who couldn’t throw strikes, who walked a bunch of batters, and with runners on base, took forever between pitches figuring out which bad pitch to throw next, which if it wasn’t missing the plate badly, ended up being an utter meatball down the middle sitting on a tee to get crushed for a home run. The first six innings took a full three hours to play.

All that imcompetence was frustrating and depressing.

But in the middle of all this stumblin’ and bumblin’ emerged two men, one from each side, a pair of strong, silent types, named Matt Chapman and Mike Trout, who rose above all the imcompetence, to restore hope to mankind, to let us believe, for just a moment, that a good, solid trustworthy person could emerge and lead mankind into a better future.

And so we went to the eighth inning, the game was tied 9-9. Matt Chapman and Mike Trout were each 3-for-4. Each had already homered in the game, Chapman twice. Each had one at-bat left to decide the game, to decide who would win and who would lose.

Sadly for us A’s fans, the mighty Chapman struck out. The Angels’ Mike Trout–steady, solid, strong, silent, competent Mike Trout– came up in his last at bat, and hit a home run. The Angels won, 10-9.

And that’s how Mike Trout outlasted everybody else to become the Last Competent Man in America.

The End.

When we look back upon this day many years from now, we will all remember it as the day that Jesús Luzardo got his very first Major League win.

Ok, maybe not. But it would have been the story, and should have been the story, if Alex Cintrón hadn’t opened his big fat mouth, and goaded Ramón Laureano into starting a brawl.

First, some background: in 2017, the Houston Astros cheated. They used video cameras and banged on trash cans to relay what pitch was coming to the batters, which is not allowed. They won the World Series that year. This past offseason, current Oakland A’s pitcher Mike Fiers, who was a member of that 2017 Astros team, revealed what the Astros did to the world. Everyone was outraged, the rest of the world at the Astros for cheating, and the Astros at Mike Fiers for ratting them out.

Lots of people involved in the cheating scandal lost their jobs. Astros GM Jeff Luhnow and Manager A.J. Hinch were suspended from baseball for a year, and also fired from the Astros. Alex Cora and Carlos Beltrán, who were also in the middle of the scandal but had subsequently been hired as the managers of the Red Sox and Mets respectively, also lost their new jobs. A leaked internal email from an Astros employee named Tom Koch-Weser revealed who was at the heart of the cheating program:

I don’t want to electronically correspond too much about ‘the system’ but Cora/Cintron/Beltran have been driving a culture initiated by Bregman/Vigoa last year and I think it’s working.

MLB tried to investigate Fiers’ accusations, but no players on the Astros would talk until they got immunity. MLB granted the immunity, and players talked to the investigators. The scandal came to light, but because of the immunity, no players got punished.

And Alex Cintrón, who is now the Astros hitting coach, did not get punished.

Remember what I wrote just three days ago about Ryan Christenson’s Nazi salute?

Giving a mere apology, and then moving on as if nothing had happened, feels inadequate to many people. Apologies are inadequate because they don’t cause any loss of dignity, any loss of status. And if it feels inadequate, the issue will not go away. People will continue to pursue the issue, to try to punish Christenson further, until they feel justice is done.

The punishment doled out to the Houston Astros was inadequate. So everybody expected, when the season started, that the Astros would have a big target on their backs. They would be hit by pitch after pitch after pitch, until everyone was satisfied that the Astros were properly humiliated.

In particular, this first post-scandal A’s-Astros series was under the spotlight. Both sides had reason to feel that the other side had not been properly punished. Mike Fiers had suffered nothing for squealing on his former teammates. Would they try to get back at him somehow? The A’s, perhaps worrying about that a bit, arranged their pitching rotation so that Fiers would not pitch in this series. And since Fiers doesn’t bat, either, there really isn’t a good way to punish Fiers directly.

So coming into this series, people were very curious what would happen. Would the A’s hit the Astros with pitches? Would the Astros hit the A’s with pitches? Would there be fights? Would there be brawls?

Why do people cheat? Let’s ask Dan Ariely, who is perhaps the world’s leading expert on cheating:

Wired: What did your tests tell you about the ways people cheat and why they do it?

Dan Ariely: We came up with this idea of a fudge factor, which means that people have two goals: We have a goal to look at ourselves in the mirror and feel good about ourselves, and we have a goal to cheat and benefit from cheating. And we find that there’s a balance between these two goals. That is, we cheat up to the level that we would find it comfortable [to still feel good about ourselves].

Now if we have this fudge factor, we thought that we should be able to increase it or shrink it [to affect the amount of cheating someone does]. So we tried to shrink it by getting people to recite the Ten Commandments before they took the test. And it turns out that it shrinks the fudge factor completely. It eliminates it. And it’s not as if the people who are more religious or who remember more commandments cheat less. In fact even when we get atheists to swear on the Bible, they don’t cheat afterwards. So it’s not about fear of God; it’s about reminding people of their own moral standards.

[…]

It’s basically about the mirror that reminds us who we are at the point where it matters.

Now I don’t want to say this is the only factor that’s going on. Take what happened in Enron. There was partly a social norm that was emerging there. Somebody started cheating a little bit, and then it became more and more a part of the social norm. You see somebody behaving in a bit more extreme way, and you adopt that way. If you stopped and thought about [what you were doing] it would be clear it was crazy, but at the moment you just accept that social standard.

Wired: What’s the difference between the person who goes along with the standard and the whistleblower who says enough?

Dan Ariely: It’s a very good question, but I haven’t done stuff with whistleblowers and I don’t really know what makes them decide to stand up. My guess is that at some point they get sufficiently exposed to other forces from outside of the organization and that gets them to think differently.

[…]

We understand cheating is bad, but we don’t really understand where it’s really coming from and how we can reduce it. The common theory says that all we need to do is to make sure we don’t have bad apples and that the punishment is sufficiently severe. I think that’s not the right approach. I think we need to realize that most people are not bad apples – we find very, very few people who really cheat in a big way – but a lot of people are cheating just by a little bit.

In most circumstances, then, in order for cheating to take place, two things have to happen:

These are the conditions which can create a snowball effect. People see other people cheating, so they cheat too, not a whole lot more than the other guy, but just a little bit more. The other guy then does the same thing, cheats just a little more than the other guy, and it grows slowly with compound interest over time, until without anyone really noticing that a line has been crossed. And it doesn’t stop until somebody with an outside perspective looks in and says, this is immoral.

The belief that other people are cheating, so that you have to cheat too, has a name: cynicism. Cynicism is what emerges in the absence of a strong moral code. Cynicism holds that everybody behaves selfishly, all the time. Instead of a matter of right vs wrong, under cynicism, morality becomes a matter of what you can get away with, and what you can’t. Leadership becomes not about being good and right, but about being strong and clever enough to get away with the dirty deeds needed to win a cynical game. And as cynicism wins, cynicism breeds even more cynicism in an ever-growing vicious cycle until morality vanishes, and all the benefits of moral behavior in a human society vanish with it.

There has always been cynicism. There will always be cynicism. It is the default mode of human nature. It is what happens when moral systems fail, when the drumbeat of moral reminders vanish. We have a president now, Donald Trump, is undoubtedly the most cynical person ever to occupy the White House. He didn’t get there alone. It was decades of growing cynicism and collapsing moral systems that made him possible.

Every single religious and philosophical system exists, or ought to exist, to expressly and directly oppose cynicism. If it embraces cynicism instead of opposing it, it has become corrupt, and should be thrown out.

The Astros cheated in 2017, because they had a pervasive culture of cynicism. They believed everyone else was cheating, and therefore didn’t see any problem with cheating better than anyone else. And they lacked leadership which would hold and communicate a strong moral code.

The Astros hired Dusty Baker as their manager because he is, besides a good baseball manager, a good man, a walking moral reminder. If you want to correct a culture which enabled cheating to grow like a cancer, you need to bring in a man like Baker, who has a wider moral perspective on life than most people. But unfortunately, Baker got thrown out of the game for arguing balls and strikes. The walking moral reminder left the room. And then the Astros within minutes reverted to that culture of cynicism.

A’s manager Bob Melvin is also a man of some integrity. The A’s could have taken revenge on the Astros for their cheating. He held that the best revenge is just to defeat them, honestly. And so they did. The A’s kicked the Astros ass all weekend, legally, on the baseball field. They did not hit a single Astros batter all weekend.

The Astros, on the other hand, hit five A’s batters during the series. Interestingly, all five hit batsmen (Robbie Grossman 2x, and Laureano 3x) were former Astros players. Perhaps that’s all a coincidence. Perhaps not.

Nevertheless, when Laureano got hit by a pitch for the third time in this series, and the second time in this game (the first being by the person he was traded to the A’s for from the Astros, Brandon Bailey), Laureano had some opinions he wanted to express as he walked to first base. And he did, and he went to first base, and all was fine, until Alex Cintrón inserted himself into the proceedings.

Cintrón stood at the top of the dugout and started chirping at Laureano. Why he would do this is unfathomable. He’s the hitting coach, not a pitching coach defending his pitcher. He took some steps toward Laureano and signaled him with his arms to a fight. Laureano claims Cintrón then said something unmentionable about his mother. Laureano charged him, and the skirmish was on.

Cintrón, of all people in that dugout, the one coach most involved in the scandal that made things tense to begin with, should not have been chirping at Laureano. Your team just hit him three times. Shut up and let him vent.

Meanwhile, Laureano should not have taken that bait. There’s a moral context here, the pandemic, that both people forgot about in the moment. If someone in the dogpile of people who ran in to break up the fight happened to have COVID-19, it could spread through both teams like wildfire. Someone could get seriously sick, or die. A brawl in a pandemic is an immoral act. Both of them should face punishment as a result, and rightly so. But what kind of punishment?

This kind of behavior could be fatally dangerous. If I were in charge, I’d have kicked both of them out for the year. But you can’t do that in arrears. You have to declare in advance that this kind of behavior is immoral and intolerable, and let them know in advance exactly what the punishment will be.

MLB has this bad habit of defining punishments ad-hoc in arrears. This does nothing to ward off cynicism, but in fact breeds it. If you don’t know what the punishment will be, if there even is one, it’s easier to believe others are cheating. And when you fail to define a punishment for breaking a rule, you also fail to define exactly how immoral the act is considered to be. So you’re neither reminding people about moral standards, nor are you fending off the idea that others are breaking the rule, which leads to cynicism.

It’s too late now for that. If MLB in arrears invents a suspension of these two men for the season, it will be be too much. Especially since the Astros sign-stealing scandal resulted in no discipline at all for their players. They have little choice, I think, but to do something in proportion to their other brawl suspension this year of Joe Kelly, which was 8 games. Otherwise, they’re just making stuff up that makes no sense.

When historians look back at the year 2020, they’ll probably spend most of their time looking at the big events, the 4,000,000 people infected in America, and the 200,000 excess deaths, and the big effects on popular culture, like baseball being played in ballparks with 50,000 empty seats. They’ll probably gloss over the little things that have changed about our lives, like the small cascade of COVID-19-triggered events that indirectly led to me falling through my ceiling yesterday.

Before COVID-19 happened, everybody in my house would head off in different directions each morning. The kids went off to school, and my wife would go to work, or her yoga class, or shopping. I, being kind of semi-retired at this point, would get a few hours to myself at home to fiddle around however I wanted.

When the pandemic hit, all those external activities became home activities. The kids started schooling over the internet, and my wife began doing her morning yoga class over Zoom. My youngest kid, who didn’t have a computer before, took over my primary one. I downgraded to my somewhat underpowered laptop. Our wifi network, which I had taken for granted until this point, suddenly was reaching its load capacity with mulitple live video streams running at the same time.

Nothing I wanted to do took priority over anyone else’s activity, so I just had to defer. I tried to stay out of their way when they were working. I tried not to do anything on the wifi network that would degrade their signal. But I began to miss my little alone time when I could do whatever the heck I wanted. So I hatched a plan to restore a little bit of what I was missing.

Our wifi router is in our attic, because that’s where it can provide the best coverage for the whole house. So some weeks ago, I embarked on a project to clean out the attic, and carve out a little workspace for myself. That would solve two problems with one stone. First, it was a place I could be by myself and not interfere in anyone else’s activity (and vice versa). Second, because the router was up there, I could plug my computer directly into the router over ethernet, and thereby not use any wifi bandwidth.

Our attic, like many attics, was primarily used as extra storage, a place to store junk you don’t need very often. And as the years roll by, you forget you even had most of that stuff at all, and you never really needed it. So I started to go through all that junk, throwing a bunch of it out, and then organizing the rest, until I had cleared out enough stuff to build a little desk up there where I could fool around on my computer however I wanted once again.

Today, my wife had organized a gathering of friends and family over Zoom, which is how family gatherings happen nowadays, if you’re not a COVIDiot. It’s a kind of game night, although it’s only night for some of us, because we’re all in different time zones. For us, it happened at 1pm, right about the same time as the A’s first pitch. As a result, this was the first A’s game of the 2020 season that I did not watch live.

Because we’re zooming and playing online games separately on our own devices, the same wifi bandwidth limitations applied, so I went up into the attic to participate. The problem here was that the sun was shining through the attic window behind me, which made my zoom background too bright, so I decided to try to turn my desk 90 degrees to get the sun out of the image.

Now, remember this is an attic, so even though I had cleared a bunch of junk out of the way, there are still various posts and pipes and beams and other house infractructure tucked away up there. One of those pieces of infrastructure is a sun tunnel, which brings natural light from the roof into an otherwise fairly dark room.

So here’s the incident: as I was turning my desk 90 degrees, I unwittingly stepped on the side of the sun tunnel tube. My leg then came down with its full weight onto the ceiling window contraption, which broke and fell out of the ceiling into the room below.

So one second, I was standing in the attic, and the next, I found myself on the floor of the attic with my leg dangling down from a hole in the ceiling of the room below me.

I wasn’t badly hurt. I scraped my ankle and achilles heel, which bled a bit, but band-aids quickly solved that problem. My self-esteem was more hurt than anything. The whole incident had been broadcast live over zoom to my friends and family! How embarrassing.

On the bright side, now I have another home repair task I can livetweet on Twitter at some point.

Anyway, after all that, I didn’t watch the A’s game live. I had considered streaming it on a second screen while we played games, but I just didn’t have the mental energy to multitask like that after falling through the ceiling.

I ended up recording the A’s game, and watching it later that evening. I don’t think I’ve ever been more thankful for a quick, efficient ballgame. The A’s won 3-1, but compared to some other low-scoring A’s games this season, there wasn’t a lot of action. Two of the three A’s runs were scored on solo homers, requiring no time-consuming rallies to accomplish. Frankie Montas was brilliant, and mowed down the Astros quite quickly through seven innings. I was able to zap through the game, skipping commercials and such, in about two hours. That was just what the doctor ordered for my wounded pride.

Well, first off, there weren’t any Nazi salutes in today’s A’s game, so that’s a relief.

If you had asked me in January what would happen in the first A’s-Astros game of the year, I wouldn’t have guessed I’d be thinking more about Nazi salutes than the Astros sign-stealing scandal. I would have said there’d be a ton of hit-by-pitches. All those cheatin’ Astros — Bregman, Altuve, Correa — they were gonna get theirs.